SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Why Duterte wasted ECQ yet again](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/04/TL-repeated-lockdowns-April-16-2021.jpg)

For two straight weeks, from March 29 to April 11, President Rodrigo Duterte reinstated the government’s most stringent lockdown mode called enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) in Metro Manila and nearby provinces.

Things have now reverted to the supposedly more relaxed modified ECQ (MECQ). But these days it’s hard to tell the various quarantine modes apart. ECQ 2.0 felt a lot looser than its 2020 iteration, and MECQ might as well stand for mock ECQ.

Still, the economic toll of this new lockdown will likely be enormous, seeing that Metro Manila alone accounts for about a third of the nation’s total output. Worse, it’s doubtful whether ECQ 2.0 helped to abate the recent rise in COVID-19 cases.

At any rate, the Duterte government must let go of its lockdown mania and decisively beef up its pandemic response (testing, tracing, the works). Right now the Philippine economy is closing and reopening in cycles, as though we’re caught in a nasty time loop. We can and should get out of this time loop now.

Economic toll of ECQ 2.0

Repeated lockdowns are like multiple stabs at the heart of the Philippine economy. And actually it takes only a few weeks of lockdown to bring the Philippine economy to its knees.

We learned this painfully last year when the economy plummeted by 9.6%, its worst contraction since World War II. Bad as that was, the ECQ implementation in the last half of March 2020 (a little more than two weeks) was enough to bring economic growth down to less than 1%. That was the country’s first negative quarterly growth rate since the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s (Figure 1).

With ECQ lasting for two and a half months, growth in the 2nd quarter of 2020 fell by a whopping 17%, easily the worst quarterly contraction in our economy’s history, plunging past the nadir of the Marcosian debt crisis in the mid-1980s.

Figure 1.

You can expect that ECQ 2.0, shorter and laxer as it was, will similarly pull down what little recovery we’ve already experienced (if at all that can be called recovery).

Trade Secretary Ramon Lopez said in a recent press briefing that ECQ 2.0 likely led to an evaporation of P180 billion from our economy, and resulted in 1.5 million more jobless Filipinos. How exactly were these figures arrived at? No one knows, but the official GDP and unemployment statistics will come soon enough.

Still, Google’s mobility data already offer us hints. Figure 2 shows the steep drop in mobility in Metro Manila upon the return of ECQ. As of April 11, mobility at retail and recreation areas was still 62.4% lower than the pre-pandemic level, and at par with levels seen back in June 2020. Similar dips happened to other mobility categories.

It’s as though government turned back time and it’s now mid-2020 all over again.

Notice that mobility across the board was starting to decline even before ECQ 2.0, suggesting that people themselves were voluntarily staying at home, alarmed by the aggressive spread of COVID-19.

Figure 2.

Because of ECQ 2.0, more and more analysts are predicting a “double-dip” recession. It shouldn’t come as a surprise, really, given the premature reopening of the economy. (READ: New surge? Duterte reopened economy too quickly)

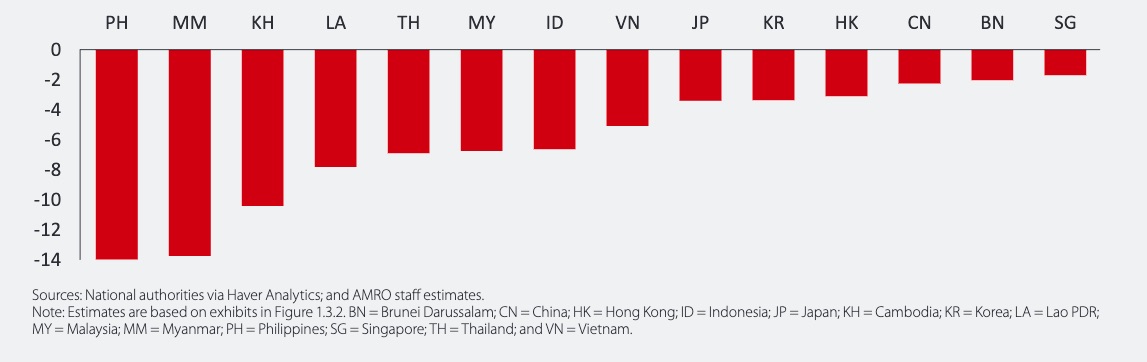

Expect the economic losses to linger. The ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO) recently came up with a study claiming that the Philippines is the country in ASEAN+3 likely to deviate the most from its potential output by 2022 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. ASEAN 3+ projected deviations of real GDP levels from trend by 2022 (in percent). Source: AMRO.

Wasted opportunity (again)

Apart from inflicting untold damage on the economy, both in the short run and long run, it’s doubtful whether ECQ 2.0 helped at all to bring down COVID-19 cases — as it was meant to do.

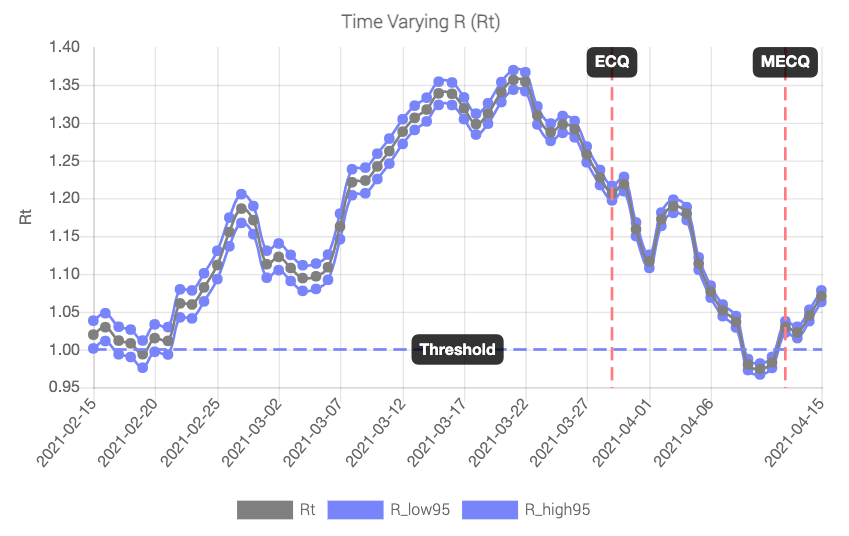

Sure, there has been an interruption in the otherwise exponential growth of new cases. And there was a noticeable reduction in the time-varying reproduction number, a measure of infectiousness (Figure 4).

But new and active cases are still alarmingly large, and the reproduction number has been going down even before ECQ 2.0 started (it’s actually starting to climb again under MECQ).

Figure 4. Source: L4H Dashboard.

More unsettlingly, the Duterte government failed to pair ECQ 2.0 with commensurate increases in testing, contact tracing, or hospital capacities — therefore wasting the lockdown yet again.

Too few tests are being conducted daily, and we know this because of the excessively high positivity rate. Contact tracing is a joke. And horrific anecdotes including patients hospital-hopping — and one being taken care of in her doctor’s car — belie government statistics on hospital capacities. (Apparently, occupancy rates at emergency rooms aren’t even counted in the official dashboards.)

At best, lockdowns are only meant to buy governments time, enough to beef up the health system, keep hospitals from being overwhelmed, and make sure doctors, nurses, and other frontliners aren’t exhausted.

But more than a year since the pandemic started, the Duterte government has miserably failed to do its homework. In consequence, the Philippine economy now is caught in limbo, closing and reopening based on the ebb and flow of COVID-19 cases. We’re like Sisyphus doomed to push a boulder up a hill ad infinitum.

To get out of this Sisyphean fate, the Duterte government must take its pandemic response a lot more seriously. Sadly, government officials (especially Duterte’s economic managers) still haven’t dropped the deadly notion that there’s a trade-off between public health and the economy. (READ: Debunking the deadly lies of Duterte’s economic managers)

Right now, sound health policy is the best tool government has to fix the economy — even more than the conventional fiscal and monetary policies.

Put another way, a healthy population begets a healthy economy. Is that so difficult to grasp?

Remember Boracay 2018?

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised by Duterte’s lockdown mania.

Remember the Boracay closure of 2018? Without the benefit of any study or master plan for the supposed “rehabilitation,” absent concrete goals and consultation among locals, and with only a few weeks’ notice, Duterte ordered the reckless, thoughtless shutdown of Boracay Island for at least 6 months.

This, despite warnings from stakeholders that such a move would put at risk as many as 36,000 jobs, cancel 700,000 bookings, and wipe out P56 billion in tourism revenues. Amid all this, Duterte only offered a puny P2 billion in economic aid. (READ: Enough of policymaking without planning)

If you think of it, the Duterte government’s lockdowns today are like massively scaled-up versions of the Boracay shutdown more than 3 years ago.

Without any regard for the human cost, and without considering sounder, less drastic measures, Duterte showed that he will unblinkingly kill people’s livelihoods along with huge swaths of the economy if he wants to — and just because he can.

Duterte is turning out to be a serial economy killer. But what else can we expect from a regime that has thoroughly normalized needless, senseless deaths? – Rappler.com

JC Punongbayan is a PhD candidate and teaching fellow at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Time Trowel] Evolution and the sneakiness of COVID](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-evolution-covid.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=455px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Just Saying] Diminished impact of SC Trillanes decision and Trillanes’ remedy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/Diminished-impact-of-SC-Trillanes-decision-and-remedy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=273px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] Son of a gun!](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/newsletter-duterte-quiboloy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=450px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Newsstand] The Marcoses’ three-body problem](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-marcoses-3-body-problem.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=451px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Edgewise] Preface to ‘A Fortunate Country,’ a social idealist novel](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/a-fortunate-country-february-8-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[New School] When barangays lose their purpose](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/new-school-barangay.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=414px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.