SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[Newsstand] Bongbong Marcos as ‘Beautiful’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/10/Bongbong-Marcos-as-Beautiful.jpg)

I was asked to reflect on the Philippine experience with political strongmen. Well, I have four points to make, and one image to share.

First point. If the conference theme, the return of political strongmen, resonates with us in the Philippines, it is only secondarily because the son and namesake of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos is now the president. It is primarily because the brutal, foul-mouthed, chaotic Rodrigo Duterte paved the way for the return of the Marcoses.

President Duterte figures in the rogues’ gallery in Ruth Ben-Guiat’s Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present, the book that helped redirect the spotlight to the term. Ben-Ghiat’s book has many arresting anecdotes but suffers (I must agree with Francis Fukuyama, in his New York Times review) from the lack of a conceptual framework. Whichever way you define “strongman,” however, you can argue that Duterte meets the broad definition: illiberal, populist, violent, authoritarian, the evangelist of the macho gospel. Duterte created the conditions that ultimately allowed Ferdinand Marcos Jr. to become president.

Second point. Relative to Philippine politics, the presidency is an extraordinarily powerful office – and for that reason vulnerable to authoritarian or strongman temptations. Our first president, Emilio Aguinaldo, was a revolutionary general who won pride of place because of battlefield victories. Manuel Quezon was a naturally gifted politician who thoroughly dominated national politics for three decades. But it was the first Marcos who took full advantage of the presidency’s vulnerability. He engineered the country’s democratic collapse in 1972, and ran a military regime for 14 years.

Third point. Marcos was a savvy politician who believed in the power of myths. Indeed, he benefited from reinvention himself. With his wife, he appropriated the Filipino creation story known as Malakas at Maganda – the Strong and the Beautiful – and turned it into one of the foundations of his so-called New Society.

The Filipino creation myth has many versions, but the common elements include the following: the gods created a largely empty universe; a magical bird lighted on a bamboo grove, and pecked away at one bamboo stalk; the bamboo split open, and the first man, Malakas, the Strong, emerged. The bird pecked at another stalk, and when it split open, out came Maganda, the Beautiful. With the approval of the gods, the Strong and the Beautiful then populated the world.

How did the conjugal dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos turn this story into a Marcos myth?

Parallel paintings

The painter Evan Cosayo depicted a young and virile Marcos emerging half-naked from the bamboo, with a white bird floating in the blue sky. In the companion painting, Cosayo portrayed a beautiful and barefoot Imelda emerging from the split bamboo, wrapped in a flowing dress made of white. These paintings were displayed in Malacanang Palace, but pictures of the painting circulated in the controlled press.

Marcos had reinvented himself as a war hero with multiple medals, the leader of a guerrilla unit in World War II. This became the basis of his reputation as Malakas. In his official biography published before his first presidential term, even his alleged survival under torture is minutely described, including an apparent episode of astral projection. And during the Martial Law regime, he oversaw a continuing campaign that portrayed him as an able sportsman, good in golf, the popularizer of the racquet sport known as pelota. His capacity to deliver extemporaneous speeches for hours on end, a la Fidel Castro, was also used to reinforce the official portrayal of him as Malakas.

Imelda, on the other hand, was a glamorous figure, the doyenne of good times, the patroness of the arts, who understood her role as precisely that of a star. Stars, by definition, are something or someone we look up to – the celebrity, the unattainable ideal, as Maganda.

But the project went beyond mere personal aggrandizement. The scholar Vicente Rafael wrote: “As Malakas and Maganda, Ferdinand and Imelda imaged themselves not only as the ‘Father and Mother’ of an extended Filipino family; they could also conceive of their privileged position as allowing them to cross and redraw all boundaries, social, political, and cultural. As such, they likewise thought of themselves as being at the origin of all that was ‘new’ in the Philippines – for example, the ‘New Society’ (1972-81) and the ‘New Republic’ (1981-86). To the extent that they were able to mythologize the progress of history, the First Couple could posit themselves not simply as an instance, albeit a privileged one, in the circulation of political and economic power; they also could conceive of themselves as the origin of circulation itself in the country.”

Fourth point. In the Philippine setting, the return of strongmen comes with a twist. The signs of return are there – and they are mostly associated with Duterte, with his so-called Diehard Supporters, and now with his daughter, the incumbent vice president: the overriding belief in the power of candid talk, military service as an article of faith, intimidation as the preferred form of interaction with critics. The Vice President, who wanted to be appointed as secretary of national defense, has assembled her own security force, separate from the Presidential Security Group. Other conditions Duterte put in place, such as the weaponization of the rule of law and the bureaucratic readiness to use violence for political purposes, remain.

But the second President Marcos is not too interested, or too invested, or not yet fully implicated, in any of these. He enjoys the advantage of not having to worry about them, precisely because Duterte has paved the way. Just one example: He does not need to consider imposing military rule on the Philippines again, because Duterte has shown him how to wield almost unchecked power without needing to declare martial law.

What is he known for, 100-plus days into his six-year term?

His emphasis on unity, his natural inclination to depend on diplomacy, his tendency to shy away from direct conflict. This is something many of his voters like about him: He’s nice, they say. He doesn’t pick fights. He’s calm, even conciliatory. The tone he struck in his inaugural address sounds like the authentic Bongbong: He is genuinely proud that he did not attack or criticize anyone during his campaign. (The Marcoses’ alternative information infrastructure on social media, which attacked or criticized opponents relentlessly, allowed him to say that.)

And then there is his own reputation, reinforced over the decades, of pursuing, or enjoying, the proverbial good time. In that sense, as celebrant in chief, as the “matinee idol” (in Executive Secretary Lucas Bersamin’s description) who adds suspense, intrigue, and importance to people’s lives, he is very much like his mother.

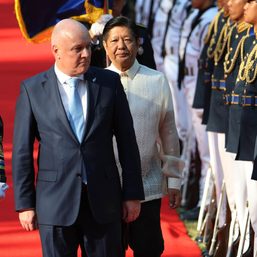

This suggests a surprising idea. History repeats itself, but with a twist: The first president Marcos was Malakas, the second is Maganda. – Rappler.com

Based on notes written for the first plenary session on “The Return of Political Strongmen” at the Asia Conference on Political Communication, October 12, 2022, in Singapore.

Veteran journalist John Nery is a Rappler columnist, editorial consultant, and program host. In the Public Square airs on Rappler social media platforms every Wednesday at 8 pm.

1 comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Newspoint] The lucky one](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/lucky-one-april-18-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=536px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Just Saying] Marcos: A flat response, a missed opportunity](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-marcos-flat-response-april-16-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=277px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

If President Marcos Jr. now becomes the new “Maganda,” then, perhaps, his First Lady now also becomes the new “Malakas”? Do you agree?