SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[Science Solitaire] No one plans to be a hero](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/10/ss-hero-sq.jpg)

If you aspire to be a hero, then you will never be one. Heroism is not a goal but a consequence, a result of the extraordinary risk you took and accepted to make other people’s lives better. Whether others’ lives really become better because of one’s action is usually beyond one’s control. Heroism is seldom marked by an award but sometimes, it is.

No one plans to be a hero. It is never in one’s “Key Performance Indicator” in life. So if you question the accolades given to “heroes” you secretly or openly think should have been given – following your own notion of “heroism” – to you (or others you prefer), you spectacularly fail in that essential criteria of “heroism.” And you probably deserve an award for that kind of phenomenal failure.

“Extraordinary” depends on what is “ordinary” at that time you were considered a “hero.” If you lived in a time and place where the majority of people reliably stop and help even a stranger in need, speak up and routinely fight against abusive authorities despite great risks, step up to solve a common crisis, we would all be scratching our heads on what “hero” meant. I personally want to live in a place and time where there would be no need for heroes.

But human nature, as has been proven by our real-world experience and data from behavioral science, has shown, that humans are not basically good. That is the bad news. But the good news is neither are we basically evil. Instead, we are both AND all the gray points along the spectrum, in different points in our lifetimes, shaped by how we were raised, whom we have become and how we bow to or rise above the circumstances we find ourselves in.

That is NOT what most religions teach but that is understandable because being consistently aspirational is also part of human nature. Otherwise, we should all just succumb, without question, to our collective earthly tragedies like a field of bowed roses. I respect those religions that, in their deep, scaled attempts, raise the bar for human nature, despite history, despite reality. I think institutions, like the Nobel Committee, that recognize how far we can rise above our darkest natures in real world experience serve the same purpose in their distinct way.

Science has been trying to capture glimpses of our human nature, to try to explain us to ourselves. But of course, the explanations about why we are the way we are, are not as clear-cut as how we explain how motors work or even how we send humans to space. Science will not be worth its salt if it does not aim to explain but when it comes to human nature, the tools to capture the complex beings that we are and the inherent traps (being aware that we are being studied), are constants that pervert the enterprise. So in terms of the science of human nature, definitive “laws” in the same way we have, for instance, the laws of motion or the gas laws, elude us. BUT we gain remarkable clues – marks that move us forward in the journey to understanding ourselves.

Two landmark experiments in behavioral science shape the notion of “hero” – the 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment and the Milgram Experiments which began in the 60’s. The Stanford Prison showed that people can lose control of the context of their participation in anything if circumstances are powerful enough. This means that extreme behaviors are most likely to happen in extreme institutions. The Milgram experiments showed that ordinary people are more willing to harm others in sheer obedience to authority, and even escalate that harm, as long as it is sanctioned.

These two experiments give us fundamental insights about human nature that tell us that one, “blind obedience to authority” is common and expected; two, extreme behavior in institutions and in its leaders beget the same in their members and allies even if individually, those members have decent and non-extreme records. These draw the line where ordinary human nature sits. That is why always only a relative few, or very few acts who call out abusive institutionalized behavior and resist obeying sanctioned orders to harm. And when they do, they mark “exceptional” territory in human nature, and therefore, are extraordinary. And lastly, I think the two experiments reveal that heroism is not a planned personal enterprise for anyone.

The recognition of anyone to be “hero” or to be emblematic of what we all aspire to become, does not mean that others who do the same but did not get the recognition, deserve it less. It is the recognition, not the acts of heroism, that we were distracted about.

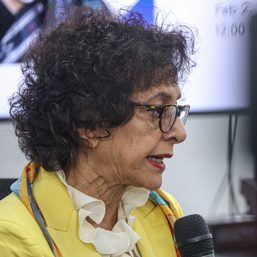

So Maria and Rappler, thank you for not planning or wishing for a Nobel Prize. Thank you to the detractors who rendered it even more painfully clear that we direly need heroes, even if it is in itself a tragic testament to the times that we do. To the rest of us, mere mortals – may we keep working on ourselves so we never have to need heroes or destructively argue on who deserves to be one or not. – Rappler.com

Maria Isabel Garcia is a science writer. She has written two books, “Science Solitaire” and “Twenty One Grams of Spirit and Seven Ounces of Desire.” You can reach her at sciencesolitaire@gmail.com.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Newsstand] The media is not the press](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-media-is-not-the-press-04132024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=281px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[FIRST PERSON] Embracing grief](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/10/IMG-067e8c4bf4fb0b4d6875e7b4ca7635e3-V.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=19px%2C0px%2C1195px%2C1195px)

![[Science Solitaire] What is an open mind?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/09/what-is-an-open-mind-september-23-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=174px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Science Solitaire] How is your forgettery?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/08/forgettery-August-5-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=292px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Science Solitaire] The very surprising thing about what makes you choose good or bad](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/04/Science-Solitaire-choose-good-bad-April-29-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=361px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.