SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

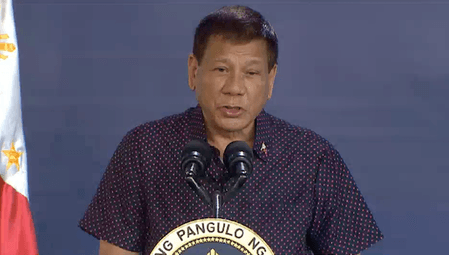

![[OPINION] The limits of Duterte’s power](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/03/duterte-military.jpg)

The following is Part 2 of a two-part series. You can read Part 1 here.

In the “Then they came for” part of the Duterte onslaughts prior to the current crackdown on communists, the targets have been mainly opposition politicians and critical journalists, and the main method employed to try to get rid of them has not been physical elimination, but throwing them in jail through false or trumped-up charges. In this part, “they” only managed to “come for” several targets, and thus far, among the latter, only one is behind bars: Senator Leila Delima.

It can be argued that Duterte does not really need to put opponents and critics in jail since he can resort to other means for getting rid of them. Through populist mobilization and the usual patronage and vote-buying, the ruling coalition shut out the opposition in the 2019 senatorial elections and, aided in part by the age-old tradition of turncoatism, easily won an overwhelming majority in the House of Representatives.

To remove the independent-minded chief justice, Maria Lourdes Sereno, from the Supreme Court, Duterte left it to the justices of the court to do the job for him. To weaken and try to discredit the opposition leader, Vice-President Leni Robredo, he has hurled false accusations against her and denounced her in vituperative and misogynistic language.

Apart from controlling the executive branch of government, Duterte would seem to be holding sway too over the legislative and judicial branches of government, judging by the great number of legislators belonging to the ruling coalition and of Supreme Court justices he has appointed. (Eleven of the 15 Supreme Court justices are Duterte appointees, and he may be able to pick a few more before the end of his term.)

Despite Duterte’s apparent control over the three branches of government, he has not been able crack down fully on opponents and critics. He may have succeeded in shutting down the country’s biggest broadcasting network, ABS-CBN, but the media remains as vibrant as ever and publishes or airs dissenting views as before. Local human rights organizations have continued to expose extrajudicial killings and other atrocities, and they have worked closely with international human rights networks. Amid the constraints of the COVID-19 pandemic, various social movements have waged protest campaigns online and on the streets.

The limits of Duterte’s silencing power can be seen in his many frustrated attempts (thus far) to have intrepid journalist Maria Ressa and former Senator Antonio Trillanes IV locked up in prison despite a barrage of court cases and arrest warrants. Both have been subjected to several years of intense and highly orchestrated harassment. In Ressa’s case, reports the Washington Post, “offline prosecution” has been combined with “online persecution,” a torrent of extremely vicious social media attacks.

Duterte may have the numbers in the country’s top executive, legislative, and judicial bodies, but he still does not have full control of the state machinery. Pro-Duterte judges and prosecutors – the main enforcers (“they”) of Duterte’s efforts to imprison and silence opposition leaders and critical journalists – have not been able to foil the workings of the country’s judicial system and other democratic institutions, no matter the severe batterings that these have undergone over the last few years.

One state institution that remains a bulwark of independence from presidential control is the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), which has continued monitoring human rights violations despite much harassment. Duterte has long threatened to dismantle the CHR, a constitutional body that is Southeast Asia’s oldest national human rights institution. He has abjectly failed.

The anti-communist drive: A pet project of the military

With Duterte’s express orders to “kill” and “finish off” communists, the next phase of the “Then they came for” onslaughts is likely to be of the bloody kind again, not just the incarceration type. The avowed targets are members of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and guerrillas of the New People’s Army (NPA), but included in the actual targets are Leftist activists whom the government deems to be accomplices of the communists. The main enforcer of the anti-communist drive is the AFP, supported by the PNP.

Since the Marcos era, the CPP-NPA has perennially been the target of counter-insurgency campaigns and operations of the military. During the early years of the Duterte administration, however, there was a decline in armed hostilities, as Duterte pursued peace negotiations with the communist rebels and even included some Leftist personages in his Cabinet.

Although Duterte and the military have worked closely together in the war against the ISIS terrorists, the relations between them have been far from steady-going. With strong US-Philippine military ties dating back to independence, the military establishment was not too happy with Duterte’s pivot to China. Moreover, the generals were also very doubtful that something positive would come out of Duterte’s peace overtures to the CPP-NPA. Duterte wooed them with hefty increases in the military budget and appointments of retired generals to key government positions, but the strains remained.

The breakdown of the peace talks with the communist rebels paved the way for a more hardline approach. In June 2020, amid the COVID-19 lockdown, Congress overwhelmingly passed the Anti-Terrorism Bill, a sweeping piece of legislation that permits warrantless arrests and allows security forces to hold individuals for weeks without charge. Three weeks later, Duterte, piqued by the CPP-NPA’s rejection of his peace terms, signed the bill into law. The Anti-Terrorism Act, however, was not really the initiative of Duterte or Congress. As reported by Rappler, it was a pet project and brainchild of military and police generals.

This indicates a curious shift in power dynamics. Instead of Duterte exercising power over the military, it was the military exercising power over him. And instead of the generals being simply the enforcer of the anti-communist, anti-Leftist onslaught, they were also the architect of it. In a sense, Duterte, of “kill them all” fame, has been turned into their mouthpiece and cheerleader.

The limits of Duterte’s power have been further shown up by the snowballing opposition to the Anti-Terror Law. Immediately after the law’s signing, lawyers’ groups and a congressman challenged the constitutionality of the law for infringing on civil liberties. In recent months, the anti-communist drive has become a public relations fiasco. When officials of the National Task Force to End the Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC) engaged in a “red-tagging” spree, labeling and accusing various organizations and individuals of being communists or communist supporters, it caused an uproar and drew widespread excoriation. Among those “red-tagged” were lawyers, writers, and other prominent personages, including two retired Supreme Court justices.

NTF-ELCAC accusations that some prominent universities in Metro Manila were being used as communist recruitment sites were roundly denounced by the academic communities of the universities tagged. Claiming that the University of the Philippines (UP) had become a communist hotbed, the Department of National Defense unilaterally terminated a longstanding agreement with UP prohibiting the military and police from entering without permission. Despite COVID, mass protests erupted on campus.

In the ongoing hearings in the Supreme Court on the Anti-Terrorism Act, the total number of petitions filed by various organizations against the controversial law has grown to a whopping 37, and a formidable line-up of lawyers has presented the petitioners’ oral arguments. Again, Duterte is being forced to contend with the workings of the country’s judicial system and other democratic institutions.

Whether or not the Anti-Terrorism Act is declared unconstitutional, Duterte and the military will just continue with their anti-communist drive. Extrajudicial killings of CPP-NPA forces and of Leftist activists have started to rise. Red-tagging is broadening even further the range of targets of this drive and could lead to another horrendous extrajudicial carnage.

Is time running out for Duterte?

There will likely be no let-up in Duterte’s onslaughts against his chosen targets until the end of his term. In going after political opponents, critical journalists, and Leftist activists, the workings of democratic institutions may pose hurdles. But Duterte will not stop for as long as he stays in power.

Meanwhile, the anti-narcotics and anti-communist campaigns appear to have significantly contributed to the spike in killings in two groups: lawyers and local government officials. The number of lawyers slain during the Duterte administration has reached 61, local executives (mayors and vice-mayors), 25. At least some of the lawyers killed were attorneys of drug or communist suspects. Other lawyers and the local executives killed were being linked to drugs.

With a little over a year left in his term, the wanna-be-Hitler is unlikely to attempt becoming an out-and-out dictator. The COVID-19 pandemic presented Duterte with a second major opportunity to take on full dictatorial powers, but he realized he did not have all the wherewithal to do so. It would have been very difficult for him to shut down Congress (as Marcos did in 1972) or turn it into a rubber-stamp legislature. Moreover, with his pro-China stance, he would not have gotten the backing of a pro-US military establishment. Congress did grant Duterte certain “special powers,” but not “emergency powers,” to deal with the COVID-19 crisis. It struck down certain “dangerous” provisions in an early draft of the bill that would have given him powers for budgetary reallocations and takeover of private businesses.

To continue with his initiatives and build on his legacy, Duterte has been grooming his daughter Sara, the mayor of Davao City, who is somewhat of the authoritarian bent too, to succeed him as president. If Sara wins in the 2022 presidential election, he may yet realize his dream of an autocracy – of a dynastic kind. Thanks to Duterte’s grooming, Sara has been topping the early surveys of possible presidential contenders.

There is a more urgent reason for Sara to win the presidential election. Political scientist Mark Thompson notes: “Outgoing Philippine presidents have had a poor track record in securing the election of their favored candidates.” If an “unfriendly” candidate wins in 2022, he or she could well help deliver Duterte to the ICC to face prosecution for crimes against humanity. The precedent for a former Philippine president spending time in prison has already been set by Joseph Estrada and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.

Certainly, the slaughterous wanna-be-dictator would not want the “First they came” saga to end in such a way that the enforcers (“they”) are no longer his henchmen but representatives of the ICC. He would dread that the poem would end this way:

Then they came for Duterte. And they brought him to The Hague. – Rappler.com

Nathan Gilbert Quimpo is an adjunct professor at Hosei University and the University of Tsukuba in Japan. He is the author of Contested Democracy and the Left in the Philippines after Marcos and the co-author of Subversive Lives: A Family Memoir of the Marcos Years.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Just Saying] Diminished impact of SC Trillanes decision and Trillanes’ remedy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/Diminished-impact-of-SC-Trillanes-decision-and-remedy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=273px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] Son of a gun!](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/newsletter-duterte-quiboloy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=450px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.