SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] Making sense of a senseless massacre](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/09/palimbang-massacre-september-23-2021-sq.jpg)

September is a month filled with ominous signs of tragedy. A hundred years ago today, the dictator cum kleptocrat was born in Ilocos Norte, bringing the country to one of its darkest moments in history and penury to Filipinos for the more than a generation. Then came the infamous declaration of martial law, whose horrors and legacies have been resurrected by the current administration. Even what was supposed to be a joyous occasion on our wedding day turned to gloom when Lean Alejandro was fatally shot at around midday and a PAL Airbus plane overshot the Manila runway, causing a massive traffic jam at the South Luzon expressway in the afternoon.

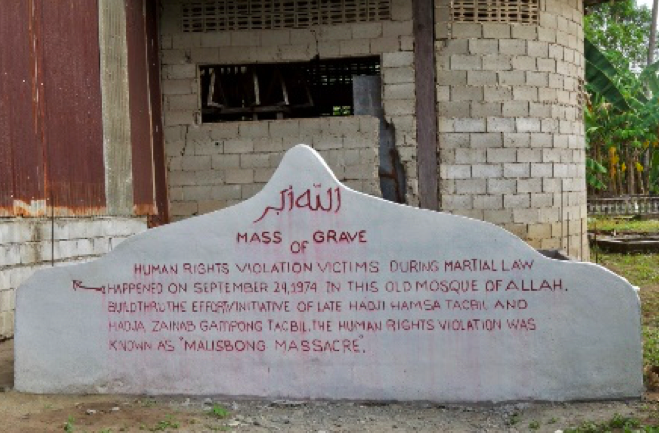

Very few however remember the date September 24. On that fateful date in 1974, atrocious carnage was committed against several Muslim communities in the Cotabato area now known as Sultan Kudarat. Partly because of distance, in time and from Manila, partly due to denials from Marcos’ apologists, this massacre has not been given proper appreciation and recognition.

As written in historical accounts and retold by survivors, a large contingent of Army troopers consisting of four battalions herded an estimated 1,500 men inside the Tacbil Mosque in Barangay Malisbong. In the meantime, women and children were separated from the men and detained in naval vessels for several days.

The Palimbang Massacre is unusual compared to other massacres the country experienced. One is the unusual number of deaths. The estimated number of casualties range from a thousand to about three thousand. The exact number of casualties remain unknown until now, which apologists use to cast doubt that the massacre ever happened.

The second is the presence of naval vessels in the Palimbang area and their participation in the massacre. Usually, it is land forces – Army, Marines, Constabulary, and military-trained and supported vigilantes – that figure out in massacres. The third is that it was the provincial governor himself who sought the intervention of the military in the area and according to eyewitness accounts, the one who ordered the execution of Muslim men detained inside and nearby the mosque.

To understand the massacre at Palimbang, it is necessary to backtrack a little. The long simmering conflict in Mindanao erupted into a full-blown war for independence and the establishment of a Bangsamoro republic in the early ’70s. One of the biggest MNLF offensives came in March 1973 when MNLF forces attacked both Jolo, Sulu, and Cotabato City. While the military was able to thwart the MNLF attack in Jolo, in Cotabato, the MNLF came close to capturing the city. Under the command of Hashim Salamat, one of three founding members, the MNLF was able to pin down the military into a small area around Awang airport.

It was only because of the timely interventions of the Air Force in providing close ground support as well as airlifting reinforcements, war materiel, and supplies that the military was able to repel the offensive. Historians can take comfort that this episode is vividly captured in a book written by the commander of the Central Mindanao Command (CEMCOM) himself, General Fortunato U. Abat, Jr.

The aim to capture both Jolo and Cotabato to declare an independent Moro state was part of a larger plan of the MNLF to internationalize the issue. Both attacks were launched in time for the Islamic Foreign Ministers Conference meeting held in Benghazi, Libya. Previous to this, the MNLF had received help from sympathetic countries like Libya. But the full-scale attacks brought to the attention of the Conference the dire situation of fellow Muslims in Mindanao. By involving the Organizations of Islamic Countries into the struggle, the MNLF could count on the diplomatic recognition and support of the powerful OIC, the pressure they could exert on the Philippine government, not to mention the funds and arms they could receive. But the Philippine government was still unaware of this strategy.

The attempt to duplicate this feat was initiated the following year. In February of 1974, MNLF forces overrun Jolo, Sulu. This time they were more successful. The city was taken over completely and the military had to withdraw. But next came the conflagration. Intent on retaking the city and avenging its humiliating loss, the military deployed naval vessels to bombard the city and fighter jets using napalm. The result would become known as the so-called 1974 Burning of Jolo.

This time, the Philippine government had become aware of the significance of the timing of big MNLF attacks. The 1974 Jolo incident coincided with the Conference meeting in Lahore, Pakistan. The next meeting of the Conference was scheduled in September in Kuala Lumpur.

The military expected a similar attack in the mainland, and assumed that it would be Cotabato where the MNLF is strongest. Because Cotabato City is a riverine area, it was necessary for the military to deploy naval assets. A few years back, arms shipments from abroad landed on the shores of Cotabato. The armaments the MNLF used proved to be of better quality and more modern than those used by the Armed Forces. And during the 1973 attack, the MNLF surprised the military by displaying seaborne operations, using amphibious capabilities in assaulting the city.

It should be noted that as the situation in Cotabato deteriorated, Marcos placed the province under military rule and appointed military officers as its governors. The first military governor of Cotabato (before it was subdivided into three provinces – Sultan Kudarat, North Cotabato, and Maguindanao on 22 November 1973 – was Colonel Carlos B. Cajelo of the Philippine Constabulary. He was later replaced by Governor Gonzalo H. Siongco, who was a brigadier general in the Philippine Army, after whom the base of the Army’s 6th Infantry Division in Awang, Cotabato is named. True enough, Siongco is referred to in historical accounts as “governor-general.”

Thus, when the military received news that MNLF rebels were massing up in Palimbang, the response was furious. It was meant to prevent a repeat of the previous year’s daring attack that almost succeeded. And also prevent the MNLF for using the attacks as part of its diplomatic offensive. Siongco acted more the gung-ho general determined to flush out suspected rebels than the civilian governor who could have interceded in behalf of his constituents. In the military’s haste to contain the rebellion, there were no attempts to separate innocent civilians from combatants. All males were considered `fair game. It thus makes sense why women and children had to be separated in naval boats while the killings ensued. Likewise, it makes sense that the bodies of those executed were buried in very shallow graves as the military began to withdraw from the area.

Even after several months, there were reports that human remains with their hands still tied to their backs were recovered from Tacbil fishpond. Human remains were also recovered when diggings began for a deep well project. Even after a few years after the massacre, residents reported seeing numerous human bones washed ashore. Unfortunately, not one of the bodies could be given proper burial nor could they be exhumed and subjected to autopsy, for this runs counter to Islamic culture.

Many years after the massacre, both Defense Secretary Enrile and General Abat denied that a massacre occurred at Palimbang. Because from the mindset of the military, what happened was not a massacre of Muslim civilians but a legitimate military operation against Muslim rebels. And because of this mindset, there was no effort to distinguish between combatants and non-combatants. There were also efforts to contain information on the massacre as national security could be invoked.

But regardless of attempts to whitewash the event or erase it from memory, the Palimbang massacre is alive in the memory of victims and residents. It is a gnawing historical wrong crying for justice.

On the 45th anniversary of the massacre in 2019, a show of solidarity among victims, their kin, supporters, local government units as well as the AFP and Bangsamoro Islamic Armed Forces, joined hands in commemorating the event. The Commission on Human Rights issued a resolution commemorating massacre every September 24 while Palimbang Mayor Joanime Kapina signed a similar resolution and marking it as a municipal non-working holiday.

Towards the end of the commemorative event, a very touching scene transpired when a contrite ranking Philippine Marine officer asked for forgiveness from the community for the crimes committed by those who wore the same uniform as his. This may be a personal act of repentance, perhaps small compared to the magnitude of the massacre. But one small step is the beginning of a long journey towards reconciliation. An official apology from the state or the military would, no doubt, ease the pain of those who bore this wound for almost half a century. – Rappler.com

Roy P. Mendoza is a former history teacher and wishes to thank the Weaving Women’s Words from the Wounds of War research project.

Voices is Rappler’s home for opinions from readers of all backgrounds, persuasions, and ages; analyses from advocacy leaders and subject matter experts; and reflections and editorials from Rappler staff.

You may submit pieces for review to opinion@rappler.com.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] A challenge to Marcos government and MILF](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/TL-Challenge-Marcos-MILF-March-25-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Political parties must embody Bangsamoro people’s aspirations](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/imho-bangsamoro-embodiment-03212024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.