SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] Tilting at the Monster of Morong](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/03/tilting-monster-morong-March-5-2021.jpg)

The following is the first in a series of excerpts from Kelvin Rodolfo’s ongoing book project “Tilting at the Monster of Morong: Forays Against the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant and Global Nuclear Energy.“

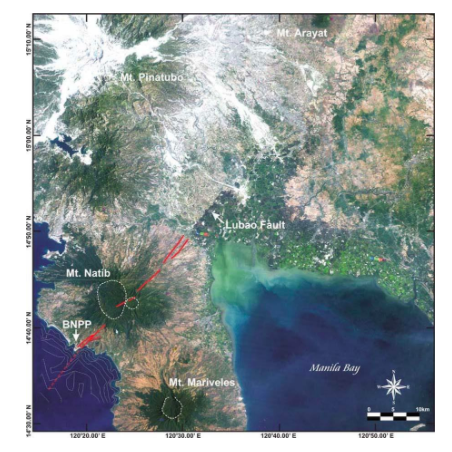

The Bataan Nuclear Power Plant (BNPP) was a poorly-considered project of the late Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos, built in the 1970s before the natural hazards it faces were properly evaluated. In the Bataan town of Morong, it sits on Mount Natib, a dormant volcano dissected by the active Lubao Fault in Pampanga and Bataan provinces, as this satellite photograph from Professor Lagmay of UP Diliman’s Project NOAH shows.

The people of Bataan call the BNPP “the Monster of Morong.” And like a monster of folklore, it refuses, zombie-like, to die. Construction was paused in 1979 to reevaluate its safety after the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in Pennsylvania. Over 4,000 construction errors were reported, but Marcos would have his plant, come hell or high water, and construction resumed in 1981.

The BNPP continued to be plagued by reports of bad workmanship and of corruption. In 1986, only two months after the 1986 People Power revolution, the Chernobyl disaster in the Ukraine happened, and President Corazon Aquino had it mothballed. A wise decision, but, inevitably, a political football ever since.

22 years later in 2008, Congressman Mark Cojuangco introduced a bill to activate it. Many people including me have opposed it. He has yet to succeed, but his efforts continue until today, as do our efforts to thwart him, including these writings.

Tilting at the Monster of Morong is the working title of a book I have been writing, subtitled “Forays Against the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant and Global Nuclear Energy.”

Why the title? My three decades of Philippine natural-hazard science was a series of Quixotic “tilting at government windmills” – to little effect, I’m afraid. In the 1980s, it was flimsy but expensive lahar dikes on Mayon Volcano; then, similar dikes but on a much larger scale at Pinatubo in the 1990s; later, expensive, graft-ridden, and useless flood-control engineering in Metro Manila’s coastal KAMANAVA cities. At present, allied with the NGO Save Our Shores, another foe is the ill-considered reclamation of nearshore Manila Bay, yet another monster that refuses to die.

This effort against the BNPP, likely my last at age 84, probably is the most important, even if it, too, may fail. Living long enough to finish the book is iffy, and so the good people at Rappler have generously agreed to run it as series of “forays” until either the book is done, or I am…

This work is far from dispassionate for two reasons. First, as an eight-year-old with my mother and siblings, I underwent the Battle of Manila in 1945. Only luck saved us from the Japanese rear-guard arson and American artillery that reduced the city to rubble, making it second only to Warsaw as the world’s worst damaged national capital. When Hiroshima and Nagasaki were bombed that August, I was deeply horrified, having a very real sense of the great killing and suffering the civilians must have endured. I have hated nuclear weaponry ever since.

Second, 60 years of environmental science have continually taught me just how terrible the global nuclear industry is, and the threats it poses to all of humankind. Cojuangco cannot be allowed to succeed, because if he does, the plant will seriously threaten the well-being not only of Filipinos, but of people in the entire region. This is my worst crisis to confront in three decades of natural-hazard scientific research in the Philippines. Several of my forays will explore the hazards in detail.

The series will delve deeply into the global nuclear industry that makes the BNPP possible. Without that international background, we cannot understand the financial shoals and the true scope of the danger it poses.

The struggle for and against nuclear power in the Philippines and the world boils down to a battle between propaganda and scientific fact. And scientific fact doesn’t seem to be winning.

Filipino pro-nuke pushers have great influence and wealth, but know very little about atomic energy, and even less about geology. They select “facts” that defend the economic benefits and safety of the plant site, but ignore “inconvenient” scientific truths that are easy to find and verify. This not only gives the people a false sense of security; it is a great disrespect and disdain for science.

For the wealthy, propaganda is fairly cheap to spread widely. Once out there, it is often quoted and spread, and is not effectively challenged. In the internet age, cellphones offer instant access to every choice between every imaginable fact and non-fact.

There are some monstrous, widely-believed non-facts about nuclear power out in the world. Two of the worst are also Cojuangco’s: “It is abundant, cheap, clean, and harmless;” and “It is the answer to global warming because it generates no carbon dioxide.” We will explore these terrible falsehoods closely.

Propaganda often triumphs overs scientific fact for two other reasons. First, science is difficult! Non-scientists may be surprised to learn that is hard for everyone — including scientists.

Second, many scientific facts are not only hard and time-consuming to gather and refine; they can be difficult to explain in simple terms. Most scientists have little time and energy to explain very clearly what they know, and so propaganda reigns.

But I enjoy teaching my science as much as I like learning it. After learning something difficult, then learning how to make it understood, the look in the eyes of someone who finally grasps it is a great reward.

And so, in this series I will try as hard as I can to clarify ideas that are complex but important to know.

This book started out as an academic report. But friends and family who shared early drafts convinced me that they must be shared more widely with the general public, because the dangers and threats of global nuclear power and the BNPP are so great. My son Austin also reminded me that many decision-makers are not scholars, and are reached more easily if not treated as such.

In academic style, my original manuscripts were sprinkled with little superscript numbers like this6, keyed to a list of references. They aid scholars, but are like annoying grit in the eye of the average reader, and so they had to go. Academic reports tag their references another way, by giving the last name of the author and date of the source in parentheses, thusly: (Reyes, 2011). But that is clumsy too, like hiccups interrupting speech, and also had to go.

And yet, my aim is to offset undocumented propaganda with documented facts, so my sources must remain available to my readers. Anyone interested enough in any of the forays to delve more deeply into its subject can e-mail me for them at krodolfo@uic.edu. Should the book ever be finished, they will reside in an Appendix of Sources.

There is also a problem with units of measure. Filipinos are my main intended audience, but I hope to educate others as well. Filipinos use the metric system for distances and temperature, but measure things like building sizes and clothing in feet and inches, so I use both. The book will have another appendix of a table of equivalents. – Rappler.com

Keep posted on Rappler for the next installment of Rodolfo’s series.

Born in Manila and educated at UP Diliman and the University of Southern California, Dr. Kelvin Rodolfo taught geology and environmental science at the University of Illinois at Chicago since 1966. He specialized in Philippine natural hazards since the 1980s.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.