SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] When judicial orders become death warrants](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/03/judicial-order-turn-death-warrants-March-12-2021.jpg)

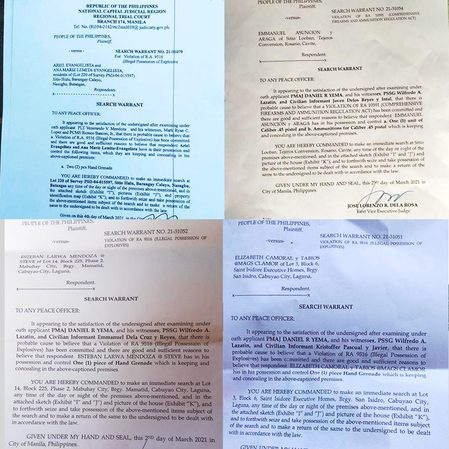

Speaking as a lawyer and as a human rights advocate, I am twice in grief over Bloody Sunday, the massacre of nine human rights activists and workers across the Calabarzon region by police ostensibly serving search warrants for illegal firearms and explosives. The second grief, the twist in the knife, lies with the issuance of those search warrants.

I say this with the utmost respect for the judiciary and its members, many of whom are my teaching colleagues and personal friends, and quite a number of whom are also my former and current students. The Bloody Sunday search warrants – the judicial orders there, issued in the name of Section 2, Article III of the 1987 Constitution that assures all citizens of their personal security – have become death warrants. The judicial orders have now become a threat to the institution of search warrants itself, and must now be subjected to proper investigation.

The Supreme Court must take action now. Judges are all on offical notice: your orders, relying erroneously on presumption of regularity, has now been turned in the hands of the police as death warrants. The eyewitnesses to the killings on Bloody Sunday were unequivocal in what they saw: executions of unarmed people, separated from their families, kneeling or lying down when they were shot.

The constitutional standard for search warrants

The Constitution makes the standards for the issuance of search warrants clear: “No search warrant… shall issue except upon probable cause to be determined personally by the judge after examination under oath or affirmation of the complainant and the witnesses he may produce, and particularly describing the place to be searched and the…things to be seized.”

Probable cause. Personal examination under oath. Particular description. Every law school student in the Philippines and like-minded jurisdictions have these words or their national equivalents drilled into their heads. Every lawyer upholds or challenges search warrants by their import. And every Supreme Court case law delves into their intricacies, ideally with the aim of the preceding statement: “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures of whatever nature and for any purpose shall be inviolable.”

The esteemed Fr. Joaquin Bernas (whose life and work we have been rightfully celebrating) noted Qua Chee Gan v. Deportation Board’s citation of a particular innovation in the 1935 Constitution that departed from the previous organic acts of the Philippines’ American colonial period, and even from the American Constitution itself: that it assigns the determination of a search warrant’s probable cause (or lack thereof) to a judge, not to any other officer. The 1973 Constitution loosened this to include “such other responsible officer[s] as may be authorized by law,” but the 1987 Constitution returned to the original formula.

With good reason. As Martial Law, Bloody Sunday, tanim-bala, and a host of other scandals marring the honor of our security forces have shown, it is that Philippine society reposes upon judges its bulwark against the abuse of investigatory powers. Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? The judges, by learning and duty, become the clearinghouse and accountability chain for the good faith, thoroughness, and professionalism of police investigation, or lack thereof.

Wrong-issued search warrants were used to detain Reina Nasino, then pregnant with River who later died tragically without her mother by her side. Likewise, similar search warrants were issued to detain journalist-activist Lady Ann Salem – and which were recently voided by Judge Monique Quisimbing-Ignacio of the Mandaluyong Regional Trial Court, nullifying the charges against her and her co-accused, trade unionist Rodrigo Espargo, as a consequence of the “fruit of the poisonous tree” doctrine. Similar search warrants mar the reputation of the judiciary with the tag “search warrant factories,” calling to mind the so-called “diploma mills” that call to doubt graduates’ higher education credentials.

The quashal (nullification) of the search warrant against Lady Ann Salem is instructive, noting lack of particularity in the items to be seized, inconsistencies in the sworn affidavits, and testimonies of the witnesses which “cannot be given full faith and credence” and should not have been. Because a search warrant authorizes the violation of the otherwise inviolable right to privacy and security, in abuse it also becomes the instrument for evidence-planting. This is not a mere or quaint fear, even discounting tanim-bala scandals. This is the reason for the “fruit of the poisonous tree” doctrine: if the court cannot trust that the search was done accountably and with integrity, then it cannot trust that the evidence it produces is in good faith.

Hence the standard of probable cause for search warrants, that the initial evidence presented to a judge in application is compelling enough for her to set aside the inviolable right, and by implication, that it was not made up to set up a raid, or frame a suspect. It is “the exclusive and personal responsibility of the judge to satisfy himself of the existence of probable cause” (Soliven v. Makasiar). This is a judicial act, not merely a ministerial one, and certainly not a “factory production.” It requires judgment, circumspection, and yes, holding police power to the higher standard. After all, the greater the power, the less the excuse.

Precedents the Supreme Court must overturn

The cases of Nasino, Salem, and those in similar plight invite revisiting two past cases where power was given, for better or worse, an excuse. In Ilagan v. Enrile, the challenge to the illegal arrest of the lawyer-petitioners was made moot by the filing of an information against them for rebellion. Umil v. Ramos, which involved a diversity of arrests, seizures, and charges, declined challenging the wisdom of Ilagan, upholding the search warrants of some of the petitioners, and thus the subsequent discovery of firearms and the resulting arrest “in flagrante,” all on information that the residences concerned were NPA safehouses.

Jurisprudence makes clear that the State has a legitimate right of self-defense. Indeed, the PNP repeatedly finds itself defending the legality of their raids, searches, and arrests – and the deaths – of the subjects of their exercise as justified in the regular course of their duty. First, the so-called “drug war,” now this so-called “whole of nation” approach to insurgency. Nanlaban, eh.

So too may the courts say that what was presented to them was compelling enough, enough to justify the invasion of privacy, the midnight knock or the dawn raid. (But then see the case of Lady-Ann Salem.) And none of this can truly be cured by a subsequent resort to the rules of law; as dissented by Justice Sarmiento in Umil, “Ilagan v. Enrile does not rightfully belong in the volumes of Philippine jurisprudence…. As I have stated, an information is not a warrant of arrest.”

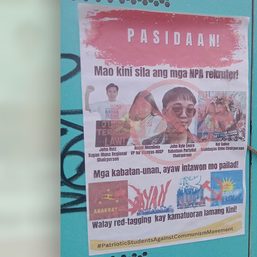

When one’s President and Commander-in-Chief says “Kill them all,” and when that same President and Commander-in-Chief once boasted of planting evidence when he was prosecutor, anything horrible is not only possible but permissible. With all the red-tagging and red-baiting, that everyone left of center must have a gun under their pillow or serve such people, good faith can no longer be assumed in the absence of professionalism, checks and balances, and proper accountability of actions.

We deserve a better PNP

Filipinos truly deserve a security force honorable, professional, and trustworthy, and the PNP has made these virtues hallmarks of their ethos. I have many PNP officers among my students and I support them in their efforts to improve their ranks. But blood spilled so carelessly and without empathy stains these hallmarks unrecognizable. I fear we are back in the days of the Constabulary, this time without even need of declaring Martial Law, and sanctified by court warrant.

It is within the ambit of the judiciary to recognize all these, and justify a searching, thorough examination of search warrants applied in the name of national security. Martial Law taught our laws that the PNP and our security services are tools of investigation and protection of liberties, not the instruments of repression and silencing, and that it is too easy to use the latter in the name of the former. And even the State’s legitimate right of self-defense, like an individual’s, cannot be exercised in bad faith.

It is a supreme irony when due process these days in the Philippines ends with blood on the streets. The judiciary, indeed the whole legal profession, led by the highest court of the land, must push back. We should not have reason to fear whether the long arm of the law is in good faith, when the courts always properly check the investigator’s homework for errors. For the Bloody Sunday victims, as for many others, the courts owe them no less. – Rappler.com

Tony La Viña teaches law and is former dean of the Ateneo School of Government.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] ‘Some people need killing’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-some-people-need-killing-04172024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[The Slingshot] Alden Delvo’s birthday](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-alden-delvo-birthday.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=263px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[EDITORIAL] Hustisya sa Jemboy case: Tinimbang ka ngunit kulang](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/animated-jemboy-baltazar-killing-verdict-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=257px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Jhed and Jonila’s fight for justice](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/TL-jhed-and-jonilla.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=411px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.