SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Amid record hunger, Duterte aids the rich](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/05/hunger-duterte-people-05072021.jpeg)

One of the most unsettling impacts of the pandemic is the historic rise of hunger.

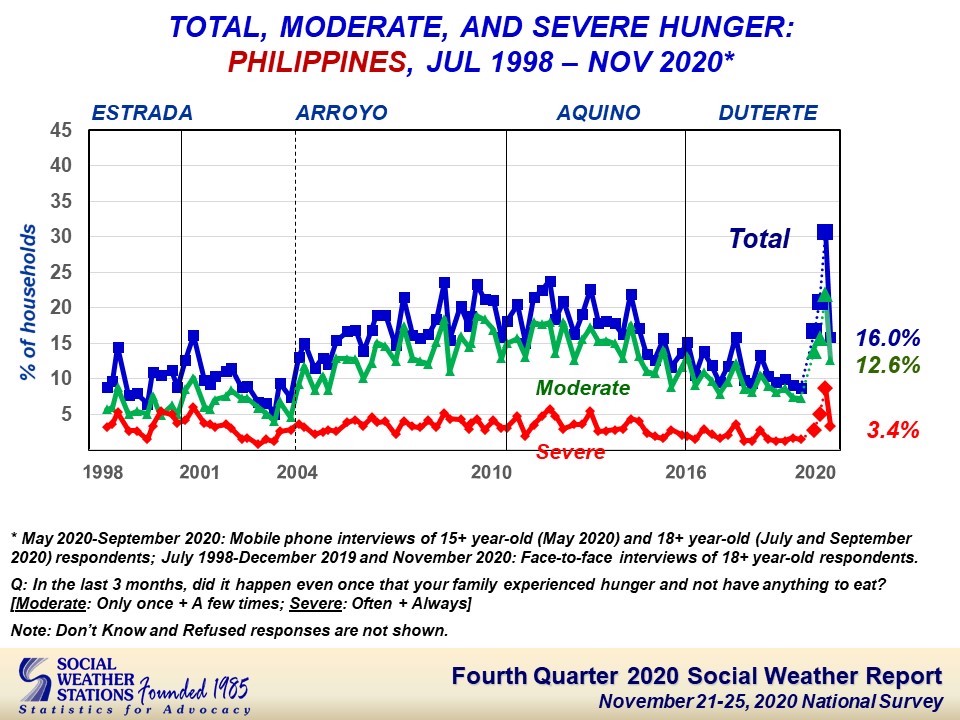

In September 2020, the self-reported hunger rate skyrocketed to 30.7% or nearly a third of Filipino households (Figure 1). That’s the highest rate since the records of the Social Weather Stations (SWS) began, and translates to about 7.6 million households.

Sure, self-reported hunger already eased to 16% by end of 2020. But we’re still talking of 4 million households, about twice the number of hungry households in the year prior.

Widespread hunger can largely be blamed on Duterte, who botched his pandemic response, which prevents us from reopening the economy quickly and confidently.

But to make matters much worse, he’s not giving nearly enough aid for the poor, and in the meantime, he’s pouring billions of pesos worth of aid to the rich as well as big business, through policies crafted by his economic managers.

Hunger worse than we thought?

The SWS findings on hunger are bad enough. But what floored me was the even more distressing survey by the Food Nutrition and Research Institute (FNRI), conducted from November 3 to December 3, 2020.

It revealed that 62.1% or about 6 in 10 Filipino households experienced hunger in 2020. That’s more than twice the highest rate reported by the SWS. (Notwithstanding data issues and some possible overestimation, FNRI’s figures are still quite disturbing.)

More than half of the respondents had difficulty accessing food, chiefly because they had “no money to buy food” (22.1%) and there was “no/limited public transportation” (21.6%).

To cope with the lack of food, nearly three-fourths of households had to borrow money, two-thirds obtained food from family and friends, and nearly a third bartered food. A fifth even had adults who ate less just so their kids could eat more.

Hunger at this scale, if it continues, will doubtless hurt people’s lives and the economy in the long run.

For one thing, the FNRI warned that we might see a worsening of nutrient deficiencies and undernutrition. Even before the pandemic, we were already grappling with a serious malnutrition and stunting problem: a 2015 survey found that nearly a third of all Filipino kids under age 5 were stunted mainly due to food insecurity.

Rampant hunger could eventually weaken people’s immune systems, make them increasingly vulnerable to COVID-19 and other viral infections, and ultimately lead to “tremendous high medical cost, lost opportunities, and economic drain.”

Amid all this, Duterte’s aid has been lamentably puny. While nearly all surveyed households received some form of food assistance from local government or the private sector, nearly half received it only two to three times throughout the pandemic. Only 63% received any cash aid, and the majority of them (59%) received it only once. No wonder more and more people are lining up at the community pantries even in the wee hours.

Aiding the rich

Duterte’s economic managers like to say that government can’t afford massive economic aid. But at the same time, they pushed for measures that effectively gave away billions of pesos to the rich as well as big business. (READ: Debunking the deadly lies of Duterte’s economic managers)

To begin with, in the middle of the pandemic they rammed through the Create law (Corporate Recovery and Tax Incentives for Enterprises Act), which Duterte signed on March 26.

Create mainly reduced the income tax rate of corporations, from 30% to 25% for large corporations, and 20% for smaller businesses.

Duterte claimed that Create “comes at an opportune time, since it will serve as a fiscal relief and recovery measure for Filipino businesses still suffering from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

But in truth, Create could not be more ill-timed. The law promises to give businesses tax relief to the tune of P1 trillion in the next 10 years. Analysts fear that this might reduce government revenues and drain the public coffers just when government needs to pay for so much, including the pandemic response, vaccines, and economic aid. (READ: Why Duterte’s corporate tax cuts won’t save PH economy)

What’s more, in a recent policy note, the International Monetary Fund recommended that governments “Refrain from introducing bespoke or knee-jerk fundamental reforms or overhauling existing tax law systems during crisis… Specifically: refrain from tax holidays; keep environmental taxes; do not cut corporate income tax rates.” (Emphasis mine.)

By boosting corporate profits, Create is essentially a gift to big business. Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III tried to spin this by claiming in a recent forum that, ostensibly, MSMEs (micro, small, and medium enterprises) will be the “biggest beneficiaries of Create.”

But that’s highly doubtful. They omitted saying that about 89% of the one million or so firms in the Philippines as of 2019 are micro enterprises, which are not incorporated and therefore cannot benefit from Create’s tax cut at all.

Dominguez also touted Create as “the largest fiscal stimulus for businesses in the country’s history.” This is part of the economic managers’ long-standing trickle-down economics fantasy: they think they’re doing most Filipinos a favor by aiding the rich.

But so long as the pandemic rages and government resorts to thoughtless lockdowns, businesses won’t significantly expand operations or hire more people just yet. Rather than help revive the economy, corporations might only declare dividends for their shareholders or even split their business into smaller companies so they can pay a 20% rather than 25% tax rate.

Besides Create, Duterte also signed on February 17 the Fist law (Financial Institutions Strategic Transfer Act). By helping banks offload their bad loans and non-performing assets – through tax perks and other incentives – this law hopes to nudge banks to lend more to the private sector, thus spurring economic activity.

Doubtless, Fist is a boon for the banking sector. But until confidence in the economy returns to full strength, banks won’t be lending too much to the private sector, and consumers themselves won’t want to take on loans just yet. Indeed, Figure 2 shows how bank lending has nosedived in recent months.

In short, Fist’s benefits won’t likely be felt by ordinary people, especially the hungry and poor.

Figure 2Finally, the economic managers are aggressively pushing for the Guide bill, which intends to park some P10 billion in Land Bank and the Development Bank of the Philippines which will, in turn, invest such money in “strategically important companies” affected by the recession.

If you think about it, P10 billion isn’t all that much. But it’s certainly a windfall for the beneficiary companies. Who’s to say which companies are “strategically important”? Duterte and his ilk? What about micro and small enterprises which need aid the most?

Denying aid to the poor

Early this year I warned that the Philippines will likely experience a K-shaped recovery. This basically means that the rich will bounce back a lot faster from the crisis than the rest of us, while the poor languish.

Just a few months later, this prediction is becoming more and more true. The thing is, Duterte himself is helping it along.

Create, Fist, and Guide are just some of Duterte’s pro-rich policies in the middle of the pandemic. In Duterte’s last year in office, expect his economic managers to push for more policies – including reforms in real property valuation and the taxation of passive income – which will again benefit mainly the rich, not the poor.

The speedy passage of Create and Fist stands in stark contrast to the snail’s pace of Bayanihan 3, an economic relief package for the poor. Bayanihan 3 was introduced in Congress as early as November 2020, but until now Duterte hasn’t certified it as urgent. In a quid pro quo, Duterte’s minions even managed to insert in the said bill P54.6 billion for military and police pensions, crowding out aid for the poor. (READ: Why Congress needs to pass Bayanihan 3 now)

Amid the pandemic, Duterte is not so much failing to give aid to the hungry and the poor as outrightly refusing to do so. Keep this criminal neglect of the Filipino people in mind in the run-up to 2022. – Rappler.com

JC Punongbayan is a PhD candidate and teaching fellow at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Time Trowel] Evolution and the sneakiness of COVID](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-evolution-covid.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=455px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[The Slingshot] Alden Delvo’s birthday](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-alden-delvo-birthday.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=263px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[EDITORIAL] Ang low-intensity warfare ni Marcos kung saan attack dog na ang First Lady](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/animated-liza-marcos-sara-duterte-feud-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=294px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newsstand] Duterte vs Marcos: A rift impossible to bridge, a wound impossible to heal](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/duterte-marcos-rift-apr-20-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=278px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.