SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[Vantage Point] How prepared are we for El Niño?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/04/prepare-el-nino-april-26-2023.jpg)

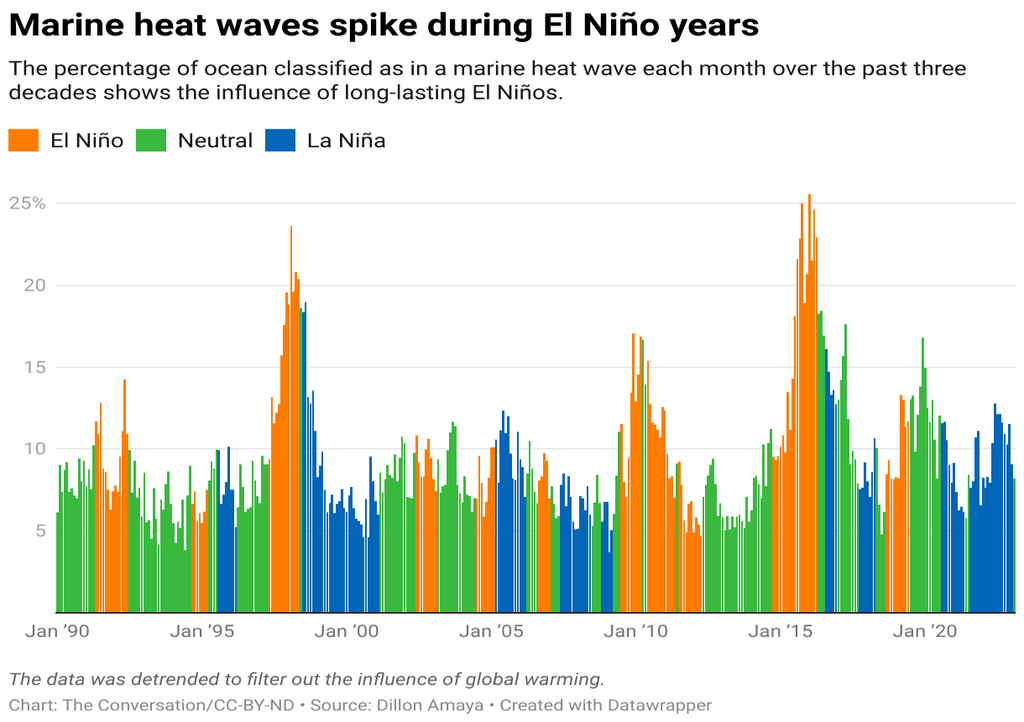

It’s coming! As winds weaken along the equatorial Pacific Ocean, heat builds up beneath the ocean plane. All weather prediction models point to the return of the climate system’s major disruptor by July 2023, the first time in nearly four years.

El Niño is the flipside of what experts call the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). It is the front to La Niña’s back.

In El Niño’s wake, for months on end, an ocean strip covering 10,000 kilometers westward off the coast of Ecuador warms, typically about 1 to 2 degrees Celsius. If you think a few degrees would not make much difference, you’re mistaken. In that part of the world, it’s more than enough to completely reorganize wind, rainfall, and temperature patterns across the planet.

A recent, rapid heating of the world’s oceans has scientists pushed on edge fearing that it will add to global warming. This month, the global sea surface hit a new record high temperature. It has never warmed this much, this quickly.

Experts are at a loss why this has happened. They’re very much concerned that, combined with other weather events, the world’s temperature could reach an alarming new level by the end of next year. Warmer oceans can kill off marine life, lead to more extreme weather and raise sea levels. They are also less efficient at absorbing planet-warming greenhouse gases.

We’ve only just passed the first three months of this year, but the heat we’re experiencing is already punishing. The prospect is terrifying: just when we thought the heat has thus far been unbearable, it can in fact get even worse.

Characterized as a weather phenomenon that causes below-average rainfall and drought, it’s highly likely to exacerbate the water shortage problem that’s already pervasive in several parts of our country.

The consequences can be devastating: crop failure, public health risks, and water supply interruption for millions of Filipinos.

According to the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) the worsening weather phenomenon will affect at least 11 provinces by August and then by October it will become 46.

NDRRMC Executive Director Ariel Nepomuceno says Ilocos Norte, Bataan, and Cavite could be hit hardest.

He says that the country is already experiencing the initial effect of the El Niño phenomenon and is projected to worsen in October to December this year or January to March 2024. Based on its latest five-day projection, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration said the heat index in a number of areas will breach 40°C in the coming days, with the highest at 48°C in Butuan on April 29.

The same phenomena occurred in 2019, when Angat Dam recorded its lowest level of 116 meters. This is way below the dam’s minimum operating level of 180 meters, and brought about one of the worst water crises in the country the Philippines in nearly a decade. Up to 61% of the Philippines was exposed to El Nino’s effects, with tens of thousands of households subjected to intermittent water supply in Metro Manila alone.

We’re all rooting for the combined efforts of the National Water Resources Board (NWRB) and the National Irrigation Association (NIA) to cushion the effects of the inevitable El Niño, through cloud seeding activities and other contingencies. The NWRB and NIA are racing against time to provide much-needed preemptive and on-crisis assistance to the already embattled agriculture sector. According to the NWRB, what’s particularly concerning is the fact that 11 million families nationwide still lack access to clean water.

These mitigation initiatives are mere drops in the bucket when we consider the relative history and modern state of water accessibility in the country. When such a basic, daily necessity comes up short too often, shouldn’t current solutions be reviewed and augmented, and other options explored?

A more recent and pressing example to consider is the current state of water supply in Cebu. The Metro Cebu Water District (MCWD) itself admitted that it was unable to reach even half of the daily demand for 639,889 cubic meters, producing and using only up to around 250,000 cubic meters in a day.

Over the last couple of years, the shortage of potable water has spread to more communities and residents in Cebu. Representatives from multiple sectors have begun flooding the district office with calls for solutions.

The MCWD, in response, has been transparent on the many challenges it faces in executing its mandate: seawater intrusion, groundwater contamination and over-extraction, clogged rainwater recharge areas, rapid demand growth, and calamities.

Solutions

It’s clear that provinces like Cebu desperately need to democratize their water sources before it’s too late. They can invest more in other alternative solutions, such as rainwater harvesting, wastewater treatment, and groundwater recharge systems.

Currently, the foremost solution is to operate desalination plants which convert seawater into potable water. The technology is already being used in countries with water scarcity issues such as Israel, Australia, and Singapore.

These desalination plants hold several advantages over other water supply solutions. First, they provide a reliable and consistent source of water, even during times of drought. Second, they do not rely on rainfall or freshwater sources, making them more sustainable in the long run. And last, desalination plants have a relatively low environmental impact, since they use seawater as their primary water source.

Leaning towards this option, the MCWD plans to utilize the 11 desalination plants located all over Cebu. The question now is: What’s taking it so long?

With the scorching heat bearing down on us, many residential and business faucets down to a trickle, and solutions being sluggishly implemented, the situation will most likely leave Cebuanos scratching their heads.

The recent creation of the Water Resource Management Office – a precursor to an expected addition to the Cabinet – offers hope that more modern solutions to the water crisis can finally be tapped. After all, the need for a secure and consistent water supply is not only a means to survival, but a matter of economic growth.

With reliable access to water, the agricultural sector can thrive, and industries – such as manufacturing and tourism – that rely on water can continue to operate efficiently. Additionally, a robust water supply ensures public health and sanitation, preventing the spread of waterborne diseases.

The Philippines and other water-locked countries have the potential for equitable distribution of water resources. The journey begins with careful study of and wise investment in alternative solutions, such as operating desalination plants that provide a reliable and consistent source of water even during times of drought. The benefits of having a secure water supply system far outweigh the costs. The government must act urgently to ensure that every Filipino has immediate and continuing access to clean and safe water.

With the abnormal warming of sea surface temperature in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean lasting for up to 18 months, it is time to deliver a sea of change in our country to ward off the extremely disruptive climate events of El Niño. – Rappler.com

Val A. Villanueva is a veteran business journalist. He was a former business editor of the Philippine Star and the Gokongwei-owned Manila Times. For comments, suggestions email him at mvala.v@gmail.com.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[ANALYSIS] Investigating government’s engagement with the private sector in infrastructure](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-gov-private-sectors-infra-04112024-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=435px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Rappler’s Best] The elusive big fish – and big fishers](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/The-elusive-big-fish-%E2%80%93-and-big-fishers.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=220px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.