SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

LONDON, United Kingdom – For oil and gas workers, the job is all about trade-offs. The money is good but the hours are long, the locations remote and the risks, as shown by the hostage crisis in Algeria, are often high.

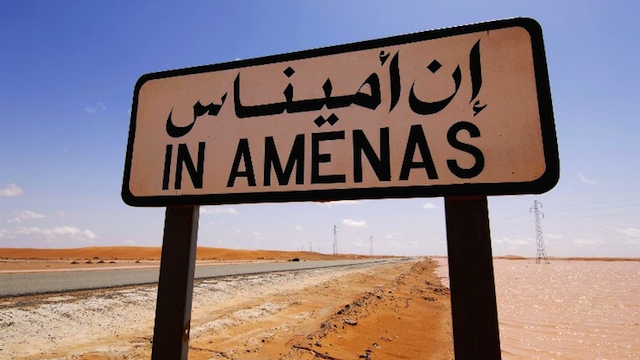

But expatriates who have spent time at sites such as the In Amenas gas complex, the scene of the deadly four-day assault by Islamist gunmen, say the job is inherently dangerous and terrorism was rarely their main concern.

“The work is dangerous in itself. Whether you’re in the North Sea or in Algeria, on an oil rig you work with pressure and explosives,” said Jeremy Perrot, a Frenchman who has worked in Algeria, Siberia and the North Sea.

He told AFP that in his two years in Algeria, before he gave up field work five years ago to start a family in France, “I never felt insecure at all.

“Algeria has been safe for so long, that I’m pretty sure the workers (attacked at In Amenas) felt pretty OK with it”.

He felt that any risks were worth taking for the money — at one point he was earning 8,000 euros ($10,600) a month — and the chance to see the world.

“It was an opportunity to travel, to go to places you would never get to go to,” said the 35-year-old. “I always planned to do it for a few years then stop and do something else.”

Although he professes not to have worried much about security, Perrot did turn down a job in Nigeria because “at the time you still had stories of people going out with powerboats to offshore rigs and kidnapping people”.

Another oil worker, a Scottish man who wanted to be identified only as Phil, said that during more than three years working in Syria, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, he never believed his life was at risk.

“I never felt in danger,” he told AFP, “although the security in most places, except Syria, was pretty mediocre — a few cop cars with rusty machine guns.”

But again, he knows how dangerous the job can be, recalling how a few years back, one of his friends was held hostage in Nigeria for 23 days along with two others.

They were beaten and tortured before a deal was struck for their release.

Alan Wright, one of the British survivors of the hostage crisis at In Amenas, said that he had never worried about security at the plant — and refused to rule out going back to Algeria once the situation has calmed down.

“It’s always been a safe place to work,” the 37-year-old Scotsman said, adding: “There’s worse places in the world to work than Algeria, even at this moment in time.”

Algeria attack ‘will not deter energy workers’

Another engineer who has worked in Libya and Syria, who asked to be identified as Vincent, said the attack in Algeria would no more deter people from the job “than deaths on the road stop people driving”.

“I feel for the people in Algeria, but you have to put it in perspective. This is a dramatic event, but it’s very rare,” the 36-year-old told AFP.

For many, the worst part of the job is the long hours spent in the middle of nowhere, where stints range from anything from four weeks on, four weeks off — “if you’re lucky” — to having just one month off a year.

Accommodation on site is often cramped and facilities pretty basic, with little in the way of entertainment.

“It’s not an easy life. The pay is good, but you have to work for it,” said Perrot.

The workers receive a basic salary, topped up by a country co-efficient — Nigeria and Angola carry the highest premiums — plus a bonus for every day spent on site, which can be as much as $200 a day.

Phil said trainees in his company could earn $60,000 a year tax-free, which then increased significantly when they took their first jobs. In Saudi Arabia, a mid-level engineer’s monthly bonuses could reach $20,000 a month.

The Scotsman said he had mixed experiences while out in the field.

He loved Syria, citing the people, the food and the history, but in one place in Kuwait, “I hated it because I was a single guy with no time off living in a tiny hot hell hole.”

The men working in the industry — as they almost all are — often struggle to maintain relationships because of the shift patterns, with divorce rife, although the workers spoke of strong bonds formed out of necessity.

“People are often very friendly because they have to spend time together. Depending on the company you work for, it can be very agreeable, with sports facilities, communal rooms to watch television,” said Vincent.

Wright and his colleagues at In Amenas would play cards and five-a-side football against the Algerian workers, while Phil brewed his own beer, which he said “tasted average… and would give a killer headache the next day”.

Vincent said working in the desert was not all that bad, and was significantly better than working on a platform in the middle of the ocean, where you had to deal with bleak weather conditions and there was no escape.

“Generally the sites are isolated, but that has its charm — you can walk around in the desert or around the site, or climb up a sand dune,” he told AFP.

He added: “These people are not oil industry mercenaries who sacrifice everything. These guys often have a taste for adventure. It’s normally fine.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.