SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

ARIZONA, United States – Two towns, two countries, one shared community.

Located in southern Arizona, Douglas is a low-income town that serves as home to 16,000 residents. It sits just a few steps away from the town of Agua Prieta in Mexico.

The porous border between the two areas has long served as a link to the same community they are both a part of. But as years went by, problems of drugs, immigration, and prejudice have increasingly built more barriers than bridges between them.

With President Donald Trump’s tirades against immigrants, the community is facing bigger challenges. While the council and residents have opposing views on Trump’s policy, they all agree on one thing: the need to fight “myths” and stereotypes pushed by federal authorities and published in the media. (READ: Trump at Mexico border: the U.S. is ‘full’)

Life in the border, as they know it, is safe, peaceful, and satisfying.

Many Americans work in Mexico and vice versa. There are also children crossing the border every day to study on the other side.

Growing up on the border

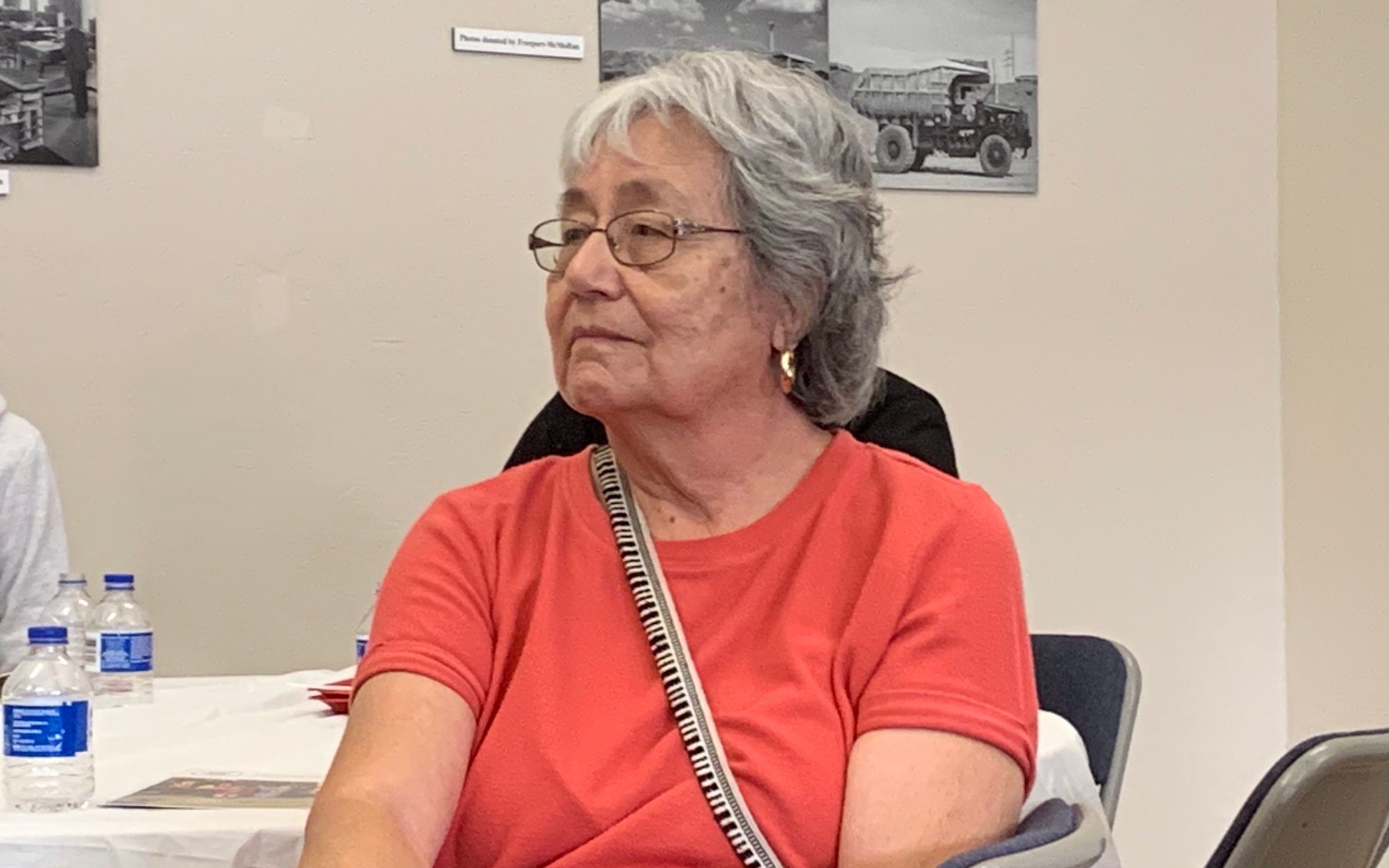

Ginny Jordan, 74, of American and Mexican descent, was born and raised in Douglas. She left town to study at a university in Tucson but came home after getting her degree.

“I love living here. This is my home. I love the culture here. You can’t go to Walmart without talking to people, hugging people. You know people here. There is a community,” Jordan said.

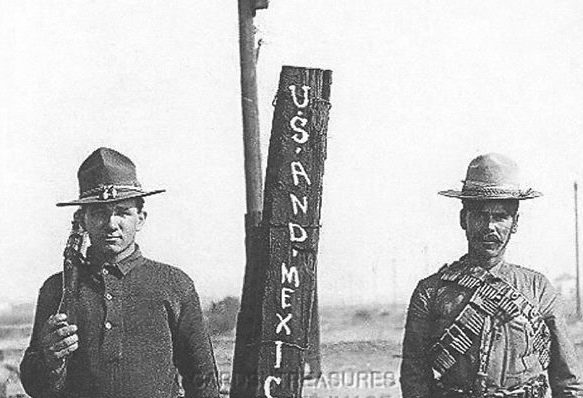

Jordan has relatives living on the other side of the border. As a kid, it only took her a few steps to cross to Mexico. There was a time in the early 1900s, she said, when only a pole served as the marker between the two countries.

Police chief Kraig Fullen said that when he was growing up, the two nations were separated only by a “5-strand, dilapidated barbed wire fence and an unimproved ditch.”

“So it was very common for the neighborhood boys to cross from Douglas to Mexico and take up a game of streetball and for them to come over and play,” Fullen said.

But things became stricter mid-1990s. Fullen recalled that when he began working as a cop in 1997, there were 100 immigration patrols in Douglas. Now, he said, these have grown to 500.

Mark Adams of Frontera de Cristo, a Presbyterian church serving the two towns, lives in both Douglas and Agua Prieta. One of his children studies in Douglas while the others study in a bilingual school in the Mexican side.

For Adams, the border is a “place of encounter and hope,” and not exclusion.

“This nation is torn. On one hand, we say America is a nation of immigrants. But we are also xenophobes, we fear those who are new, those who are not us,” Adams said.

Small town, big challenges

The daily challenges facing Douglas are not all unique to the tiny town. Mayor Robert Uribe and Fullen emphasized that the crime and drug problems in Douglas are lower compared to other places, including other border towns.

Fullen said property crimes are the most common kind committed in Douglas. Two reasons, he said: either for narcotic use or people stealing due to financial constraints and poverty.

“There is a misconception that because we are a border community, any drug is available any time and in any form,” Fullen said.

The town is “popular” for its marijuana problem. Two years ago, Mexican drug groups dropped around 150 pounds of marijuana on the US side. These items, upon dropping on US soil, were then picked up by their accomplices and partners.

To address the problem, Uribe talked with his counterpart, the mayor of Agua Prieta, and the Mexican consulate.

“We haven’t had the issue again….So far, so far. We need to collaborate to address it,” Fullen said.

There is also the perennial problem of illegal drugs transported across the border using vehicles. Federal agents are mainly tasked to monitor and control this.

For Adams, the drug issue will not be solved until it is viewed as a health, and not a crime, issue.

On top of this, the town faces a slow economy. Uribe said Douglas has suffered from poor growth in the past decades.

Uribe initially opposed the creation of a border, saying, “We don’t need barriers, we need more commercial ports of entry.” But later on he changed his mind.

Unlike some border communities, Douglas has only one port of entry for everyone. They want another port to boost commerce and trade of their financially-deficient town.

It is this same reasoning that the mayor uses to defend his vote, together with the council, to agree to Trump’s border expansion.

He said their decision aims to trigger the much-needed economic activity in the town via the influx of workers and federal officers, among others. But Adams maintained this is only a “temporary economic gain” and will not benefit Douglas residents in the long run.

Moral dilemma: Education

The town also faces a far consequential issue: education.

On weekdays, from 2 pm to 6 pm, long lines of vehicles could be seen along the border. These are parents picking up school kids to get them back across.

Students can study in Douglas schools as long as they can present a document showing a town address.

Ana Samaniego, the superintendent of Douglas Unified School District, said this is a problem because many could not present government documents.

“This is our reality. I tell them that I need them to bring me an address and if they cannot provide it, they cannot enroll in our schools,” she said.

“This provides another barrier…. We have instances when US-born children, who cannot speak a single Spanish, have to reside in Mexico because their parents could not present it,” Samaniego said.

“They end up leaving. They deserve the education but because of the laws, they could not. We have to follow the laws,” she added.

With the current stricter policy at the border, students have to line up as early as 5:30 am to get to class at 8. More often than not, however, students still end up being late.

“My daughter just got detention because she arrived late after crossing the border in the morning,” Adams said.

Samaniego said it takes at least two hours for a car to cross the border and at least an hour to do so by walking.

Sad reality, future

With the complexity of the issue, officials said it is so easy for the public to rely on stereotypes of border communities.

Officials and residents of Douglas also sought to set the record straight. The problems at the border did not only start under the Trump administration. The border fences looked almost the same as they were under the Clinton and Obama administrations, they said, except for the concertina wires installed under Trump.

“They should not cast all negative on the border. It’s hard to push back because we are already at a disadvantage, we are far from the cities. Such attack to us is unfair,” he said.

“The federal government should try to go here and talk to the people, to know the reality,” Uribe said.

As for Jordan, she could not help but mourn the changes in her hometown.

“I am sad. I have family there. Now, there is hatred around us. Our lives occur in both sides. We are a community that happens to have a border between us.”

“And now they want to bring this ugly fence that won’t let me see…When I go to my backyard, I look to the south and I see the sky, I know that Mexico is there. They are part of who I am and now there is them versus us.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.