SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

TIJUANA, Mexico – Rejected by the United States, hundreds of asylum seekers, mostly from Central America, found refuge on the other side of the border.

Nancy*, 22, risked everything for a chance at a better life. In August, she and her family traveled by train from San Pedro, Honduras, to the US-Mexico border in Tijuana to escape gang violence and harassment.

The journey was life-threatening. Nancy’s two-year-old son fell from the moving train and nearly died. After 42 days, Nancy, her husband, their son and 9-month old baby, and her 14-year-old sister Brenda arrived in Tijuana.

Nancy and her family soon realized that their difficult journey was not yet over. In Tijuana, they were welcomed by detention, hunger, and confusion. Mexican immigration authorities placed them in a packed detention center. Her kids got sick.

They were eventually released and allowed to work but with practically nothing on them, they didn’t know where to go, and how they would survive.

They were directed to their first shelter, only to find out that they each have to pay P10 ($0.52) per meal – a necessity they could barely afford.

Then they were informed about Instituto Madre Assunta, a Catholic shelter for women and children migrants, where Nancy, her kids, and her sister could stay for free, with nearly a hundred other migrants. (READ: Love thy neighbor: U.S. sanctuary churches protect migrants under Trump)

Ultimately, what Nancy wants is to seek asylum in the US. It was a legal method to gain residence in the nation but with Trump’s crackdown even on legal migration, thousands are stuck in the Mexican border, waiting for their turn to apply.

US authorities have recorded a dramatic rise in migrants’ detention over the past year. Many of these migrants fled chronic poverty and gruesome gang violence in Central America.

For the migrants, this could mean one thing: a vicious cycle of traveling hundreds and thousands of miles to escape violence and persecution, only to arrive somewhere faced by the very same fate.

Escaping hell

It was a simple life for the family back in Honduras. Nancy was a homemaker while her husband worked as a driver for a soda company. But in August, they decided to flee.

“We left Honduras because of the gangs. The gangs pursued our other brother to join them. They kicked us out of our home, as well as 50 other families in the community,” Nancy said in Spanish.

At the time, she said, their area was controlled by the MS13 gang. But before this, rival group 18th Street Gang had control over her community.

The gangs stole her husband’s motorcycle and beat him so hard that he had to get surgery.

“He had to have a wrist operation. It was too much. That’s why we decided to leave,” she said.

“Now, my husband just wants us to stay in Tijuana. But I want to seek asylum, to work and to give a better life for my children. We need help because we have suffered a lot,” Nancy added.

Nancy said their family back home had no idea where they were or if they survived.

Livia*, 28, and her 8-year-old son traveled from Ecuador to the border in Tijuana to seek refuge in the US.

She said she fled Ecuador because of religious persecution – her devout Catholic family despised her for wanting to abandon their faith and become a Christian instead. Her father, she added, physically abused her.

On September 17, Livia and her young son headed to the US border wall in San Luis near Yuma, Arizona. They climbed and jumped over the high fence.

Livia could not help but turn emotional as she recalled her ordeal. They were caught by a Border Patrol officer, who immediately brought them to a detention center.

“The border patrol who caught us was professional. But a female officer in the center yelled at us,” she said, adding that her son heard everything.

Those who cross the border illegally can seek asylum, with border officers supposedly interviewing them to assess if they have “credible fear” of being persecuted in their country. But with current policies and the deluge of asylum seekers, the processes have become increasingly difficult.

Asked how her son was taking the situation, Livia said, “My boy says he is okay but I know that he is really not.”

Livia said she is working on getting asylum in the US but it is difficult. “There’s an attorney that comes over here. We already have a court date but I have not yet done any of the paperwork,” she said.

Seeking asylum

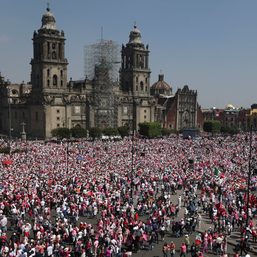

Migrants continue to troop to Mexican border cities, following two US immigration policies: metering or the process by which federal immigration officials limit the number of migrants seeking asylum at borders; and the Migrant Protection Protocol (MPP), commonly known as the “remain in Mexico” policy.

In metering, asylum seekers are given numbers – sometimes reaching thousands. The federal authorities would call a limited number per day.

If migrants do not show up when their numbers are called, chances are they have to start from square one. This prompts many migrants to camp along the border, waiting for their turn.

The MPP requires migrants who have applied for asylum to wait in Mexico – not within the US – until their scheduled court date.

Sister Salome Limas of the shelter said the waiting time 6 years ago was between one month to a month and a half. Now, she said, it takes at least 4 months.

“You have to queue in really long lines to get an appointment to seek asylum. You need to wait for that number in Mexico and then when you seek asylum, you have to stay in Mexico, as if Mexico was a safe country to be in,” Limas said.

“It is also very unfair sometimes because the judge calls them at noon but still the authorities would demand them to be there at 4 am. These are women with children and these are dangerous spots. They don’t have money to pay the hotel near the border so what most people do is to just sleep there,” she added.

Shelter

Instituto Madre Assunta has an original capacity of 44 beds but there were times they would accommodate 150 people. On the day of the visit, 87 women and children were living in the shelter.

Carefree children would welcome you to the shelter. On the surface, they appeared to be the regular kids immersed in enjoyable activities, playing with toys. Little boys and girls could also be seen using the slide on the far side of the compound.

But a deeper look would reveal the harrowing experiences of the children. While an emotional Livia was recounting their painful experience, her son sat beside her and did not leave.

Two boys entertained guests and offered hugs while telling visitors, “We like visits.”

“You can see they are very attached to their mothers. They are very sensitive, they also have been through a lot even though they are just young kids,” Limas said.

During one Sunday visit in October, mothers were seen preparing dinner. Food included bread with mayonnaise, a few cupcakes, and a cake.

Still, hope

With nothing left, thousands of migrants like Nancy and Livia continue to live their lives day to day in uncertainty and distress. There was no other option but to wait. Until when? No one really knows.

“I don’t want to stay here for a long time. I don’t feel safe in here. I am scared….When I try to go to sleep, I think about everything that happened and what could happen next to me and my son,” Livia said.

If there is indeed a limbo, these asylum seekers are in it: wanting to go to a country that does not want them, coming from a hell they don’t want to go back to, and stuck in uncertainty, danger, and confusion at the Mexican border.

“Physical wall is not our main problem. In the end, those kind of walls, people always find a way to go over it. Our main problem is the wall of ignorance and the wall of invisibility,” Limas said.

– with a report from Agence France Presse/Rappler.com

*1 MXN = $0.052

Under the supervision of Professor of Practice Vanessa Ruiz, students from Arizona State University’s Cronkite News–Borderlands Bureau also contributed to this report.

*Editor’s Note: Surnames are being withheld to protect the identities of asylum seekers and the safety of their families back home.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.