SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

YANGON, Myanmar – Editor in chief Thaung Su Nyein was excited when the government allowed private daily newspapers back in Myanmar last April. Eleven years after starting his weekly publication 7Day News, he was finally able to launch a daily edition. Yet readers took one look at it and said, “This is not a newspaper.”

At a time when Newsweek bid its print edition farewell and prominent American newspapers are put up for sale to stay afloat, print media is thriving in Myanmar, also known as Burma.

For 50 years, the former military junta imposed censorship, making it impossible for independent news groups to publish daily. All this changed when the former hermit state opened up in 2011, and started political and economic reforms. Now, street hawkers struggle to carry all of 12 private daily newspapers they peddle to motorists stuck in Yangon’s increasingly frequent traffic jams.

READ: Myanmar ends media censorship

Thaung Su Nyein’s dream-come-true was not exactly what he expected. 7Day News and other dailies in Myanmar now struggle to survive. Besides circulation and logistical problems, he said readers’ old habits die hard.

Audience attitudes and journalists’ skills have yet to catch up with the breakneck changes in an industry where the Internet and social media are starting to make and again remake the news.

“The readers felt that it was not newspaper-like because they were used to the government newspaper for 50 years,” Thaung Su Nyein told Rappler. “That’s the only form of news reporting that they know.”

‘Readers want government news’

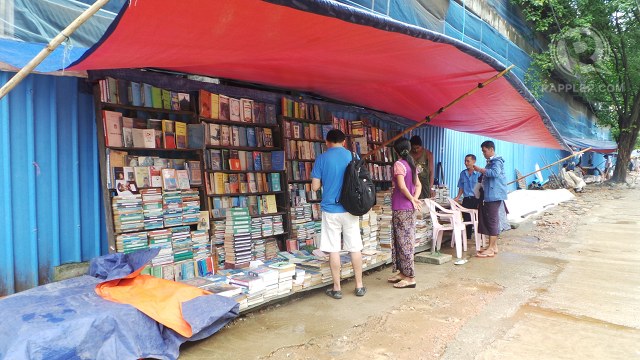

A country of 55 million people, Myanmar has a rich reading culture. Makeshift bookstores dot the streets of Yangon, where buyers can find secondhand books ranging from encyclopedias to Mao Zedong’s quotations. In bus stops and tea shops, bystanders hunch over newspapers, known in the country as journals.

So when the so-called daily era began in April, Thaung Su Nyein and other editors expected readers to shift from their weeklies to their dailies.

After all, this was people’s chance to read something other than government mouthpieces like the New Light of Myanmar, which opposition leader and member of parliament Aung San Suu Kyi laughingly calls “The New Blight of Myanmar.”

Yet like many things in Myanmar, the transition is complicated.

“A lot of the readers criticized our layouts, the designs,” said Thaung Su Nyein.

“When we’re talking about publishing a new newspaper, we’re not just talking about developing a new product within our company but having to struggle to develop the entire category itself. It’s almost as if this is the era of Ford and his invention of the automobile.”

One of Yangon’s best-selling newspapers, 7Day News was forced to change its look. Still, readers were not satisfied.

“For the past 50 years, the government newspaper always carries who the president met yesterday on the daily front page. On the back page will be the vice president or the president’s wife. It’s that kind of VIP-heavy feature coverage. So I think people expect to see a lot more official news in the newspaper,” said Thaung Su Nyein.

Taking a page out of state media, his newspaper now features more government news. It is ironic for a publication that just 3 years ago defied the military junta by putting a photo of Suu Kyi’s release on its cover. Back then, even news items and photos of Suu Kyi were banned. 7Day News was suspended for two weeks but sales more than made up for the absence.

“There was a Princess Diana effect that she had. Everything that featured her, a book, a magazine, an article, everything will sell but nowadays it’s become much more common as she became more accessible. People value rareness. When you become a politician, you’re in the news everyday,” said Thaung Su Nyein.

Reader behavior also got Zaw Ye Naung perplexed. In his Eleven Media Group, said to have the largest circulation, he found that readers still prefer buying the weekly paper over the daily.

“People think if they read the weekly journal, they cover all the news. They know all the articles, all opinions. For the daily, it’s not covered. It’s only one day. The weekly is about 600 kyats ($0.62). For the daily, it’s 200 kyats ($0.21) so they compare it,” said the Eleven Media director.

Instead of phasing out the Weekly Eleven News, the company even uses its profits to subsidize losses from the Daily Eleven. It is the same story in 7Day News and other media companies.

With the government issuing over 30 licenses for daily papers, competition is already fierce. Reader behavior added a new dynamic.

“The weeklies have actually become our main competitor now. Every daily news publisher is competing with his own weekly plus the weeklies from others,” said Thaung Su Nyein.

Fresh grad reporters, 30-something editors

Readers and media owners are not the only ones adjusting. For decades, journalists in Myanmar only had weekly deadlines to worry about.

“They are not used to doing daily reporting,” said Toe Zaw Latt, Yangon bureau chief of DVB, formerly known as the Democratic Voice of Burma, an exiled media group that returned to Myanmar last year.

“We did daily reporting from exile. One of our privileges is we were trained in lots of places like Sweden, Holland, Norway, Thailand. We got lots of training.”

It is a different story for most media groups in Myanmar, where schools use outdated textbooks and curriculum, and news organizations are forced to train new hires.

Decades of censorship also meant a new generation of journalists is only just emerging. Yangon’s newsrooms are filled with reporters easily mistaken for students or interns.

For example, Zaw Ye Naung, also broadcast and online media editor, is just under 30. He said, “The daily newspaper’s chief editor is about 31. All the other executive editors are 30 years old. The age range for journalists in Eleven Media is 22 to 32.”

These young journalists have much more to learn on top of the daily news grind. Veteran journalist and former political prisoner Win Tin said reporters and editors have yet to let go of old practices.

“Up to now, our expression is very limited. They report only facts: a meeting is held, where, and such and such. Opinion and editorials are very limited. So that, in a nutshell, means self-censorship among the journalists,” said Win Tin who founded the opposition party National League for Democracy with Suu Kyi.

Apps and Facebook first

While the daily newspaper is a novelty, journalists have already experimented with another publishing tool: the smartphone.

Kyaw Min Swe’s The Voice was the first major publication to introduce mobile apps, hoping to expand readership to include an estimated 6 million Burmese abroad.

“In the very near future, the media will change a lot again because of social media and also digital media. We already have a mobile application, an iPad application we launched last year, even before we had a daily newspaper in April.”

“I prepared because I know the future of media is online and mobile,” he said.

It is a bold statement to make in a country with frequent power outages and an Internet penetration rate of one percent to 3%. Yet the entry of foreign players in the telecommunications industry in July is expected to boost mobile access to 80% of the population by 2016.

The near monopoly of Facebook in Myanmar cyberspace already got 7Day News to again shift gears.

“Facebook has become a sort of an aggregator of content, news feeds, not just social sharing. It’s become a really significant platform even for news organizations like ours. We will tend to the Facebook channel first, put breaking news on Facebook before tending to our website. That’s how important it is,” said Thaung Su Nyein.

While figuring out how to make his newspaper viable, he is already looking ahead by tying up with HTC. Under the agreement, the smartphone manufacturer will automatically update headlines on the 7Day News app when a user turns on data connection. It will even pre-install the app in new handsets.

Eleven Media also aims to catch the digital wave through its web TV, featuring newscasts, documentaries, travelogues and talk shows.

“Now, it’s very difficult to use Youtube,” said Zaw Ye Naung. “But in the future, maybe Internet will be better and online banking is settled, people can spend time in other spaces. Now, there’s nothing to do online so they are all on Facebook.”

‘Printing press to multimedia’

Observers predict that Myanmar will be the last country in Southeast Asia where print will survive.

Despite the increasing popularity of the Internet and social media, Kyaw Min Swe also thinks the medium will not threaten newspapers anytime soon.

“Due to the infrastructure and knowledge of people, within 5 or 10 years, Internet is not a big challenge for print. But we are going to establish our newspaper as multimedia. Every newspaper in the world is going multimedia. We are so far behind the international [media]. We are still at the very first step, the printing press.”

Whether it is shifting to daily news or real-time reporting online, Thaung Su Nyein believes the lack of media literacy for both news consumers and producers poses a great challenge.

“I’m taking into context the capacity that we have compared to the distance we want to travel. It’s like trying to go to the moon not with a rocket but with a slingshot,” he said.

To him, the real mark of progress will be the time his readers recognize that it is not the medium but journalistic content that makes news. – Rappler.com

This story was written under the Southeast Asian Press Alliance Annual Journalism Fellowship (SAF) Program 2013. Rappler multimedia reporter Ayee Macaraig is one of the 6 fellows of the program.

Related stories

Myanmar: Prison, parliament and the Internet

Battling Myanmar’s Outdated Cyberspace Laws

Forward, back goes Myanmar transition

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.