SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Travellers say the best time to see Angkor Wat is either during sunrise or sunset. Both times unravel Cambodia’s historical landmark in its prime majesty. As light tussles with darkness, the sillhouette of the towers and trees emerge and a picturesque reflection is painted on the water surrounding the main temple.

Young Yoshiaki Ishizawa, in March 1960, caught this perfect moment without knowing it marked the start of his lifelong work of conserving the once unprotected ancient site.

Ishizawa, now 79, was a visiting student from Tokyo’s Sophia University at that time. He was conducting a research on French studies. An abundance of French people in the country due to France’s colonization until 1953 of the Southeast Asian peninsula known as French Indochina brought him there.

It has been 5 decades since he first saw Angkor Wat but that pivotal summer afternoon remained very vivid to him.

“The sun was shining on the [highest point] of Angkor Wat. The sun was shining, it was all red and the huge spiral of the temple at 65 meters high seems to be piercing the clouds,” he recalled in an interview with Rappler.

“My whole outlook [in] life changed afterwards,” he added.

His interest in studying the temple and the society that lived in it has grown since then.

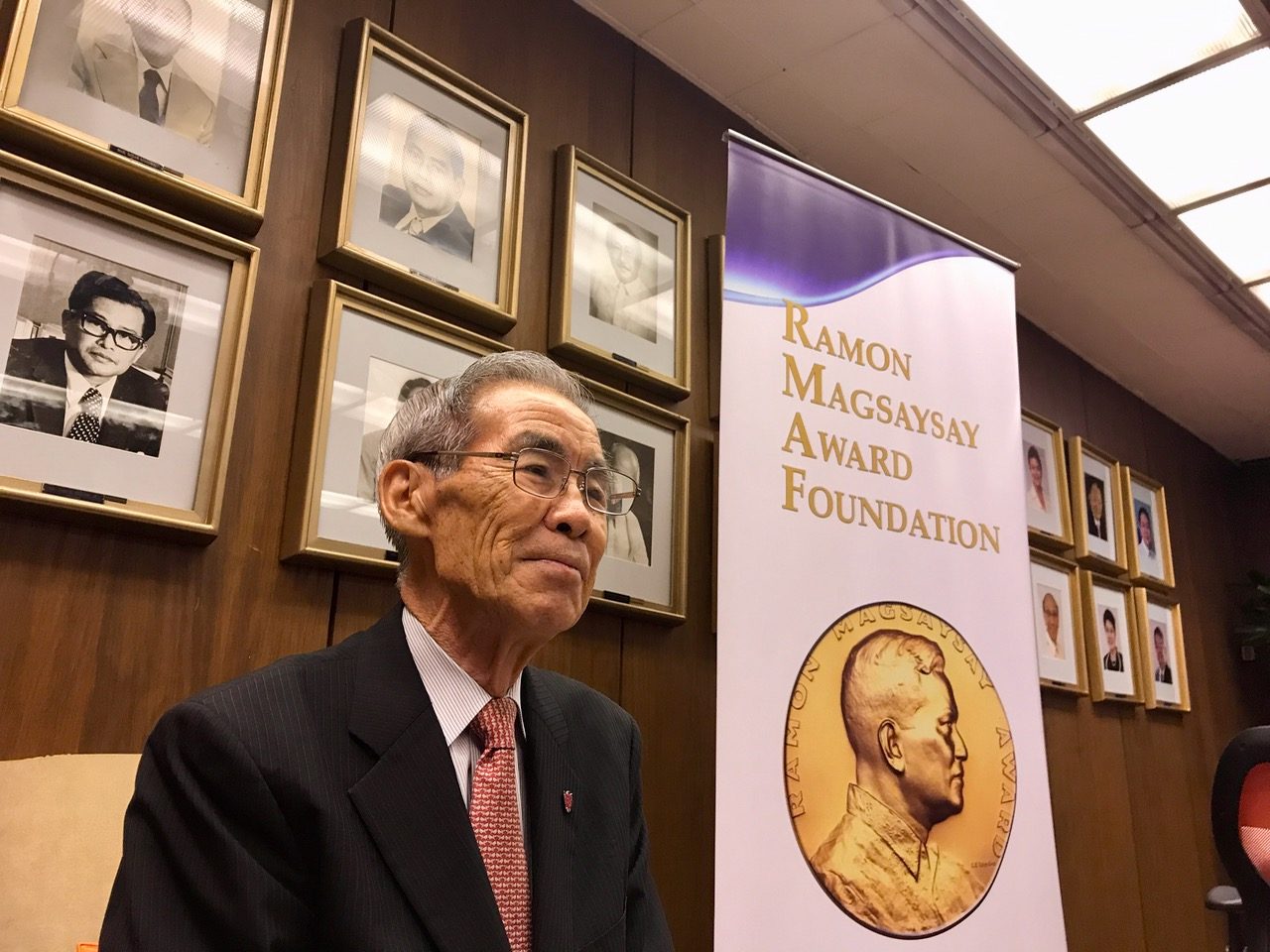

He has authored several research publications on the Angkor Wat, Cambodia and the ancient Southeast Asian civilizations. But the most notable part of his array of accomplishments is his unique approach in restoration, which led him to being recognized as a Ramon Magsaysay awardee in 2017.

Conservationists killed

The Angkor Wat is a 162-hectare temple complex in the Cambodian province of Siem Reap built during the time of the Khmer empire. Angkor is the Khmer word for city while Wat is for temple. As a “temple city,” the complex served as the capital of that ancient civilization.

The complex was originally built in honor of the Hindu god Vishnu but was eventually transformed as a Buddhist temple. Guinness World Records considers it the “largest religious structure ever built.” It is also a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Time and weathering has threatened the temples inside the complex that dates way before the 12th century. Conservation efforts were suspended due to the civil war instigated by the communist Khmer Rouge from 1967 until their fall in 1979.

Although it did not gravely damage Angkor Wat, the war killed Cambodian conservationists whom Ishizawa worked closely with.

“I have many Cambodian friends and so I used to go to Cambodia very often to meet them… I call them about [problems of Angkor Wat]. But unfortunately due to the long civil war, many of these experts were killed only 3 of them managed to come back,” he said.

“That’s how [I] had the idea of saving Angkor Wat,” he said.

Right after the war, in 1980, Ishizawa continued to work with Cambodian agencies and international organizations to campaign for awareness and support for the heritage site’s conservation.

As a historian and an educator, Ishizawa’s approach to conserving Angkor Wat was educating the Cambodians so they themselves can participate in the preservation process.

Culture and conservation

He led the the Sophia University Angkor International Mission (Sophia Mission) in 1989. The mission conducted research, training and conservation work.

Ishizawa brought in Japanese masons to work with their Cambodian counterparts to learn the proper conservation techniques. He also encouraged young Cambodians to study conservation-related degrees in Sophia University where he served as President from 2005 to 2011.

“I want the young people to take and develop an interest in the monument of Angkor so I bring them over to the site of the monument and excavate the place along with them,” he said.

“By the work that they are doing there, they will learn their own history and their own culture. The youngsters would take interest in order to understand their own identity – who they are, what they are,” he said.

He viewed the continuing conservation project as not just rebuilding Angkor Wat but also rebuilding Cambodian identity itself.

Unlike the Japanese who have a strong affiliation with their culture, Ishizawa said Cambodians did not have this opportunity because of colonization, describing it as a “great loss” for them.

He believes that exposing the young ones in the preservation would make them reconnect with their roots.

Each portion of the whole Angkor Wat complex tells a story of how the original Khmer inhabitants lived – their agriculture, art, urban planning, among others.

“The monument is extremenly large and within the monument there are so many things that we can learn hidden [there],” he said.

Cultural preservation

The Sophia mission did not only focused on training young conservationists, it also campaigned to raise awareness among Cambodian children through the establishment of the Center for Education on Angkor Cultural Heritage in 2009. The Preah Norodom Sihanouk Angkor Museum, which houses Khmer artifacts was also constructed.

They also founded the training center and hostel, Sophia Asia Center for Research and Human Development in Siem Reap, for Cambodian and international scholars. (READ: Top 5 tourist destinations in Cambodia)

Ishizawa never expected to gain an award for the efforts he led. “I didn’t think it was anything at all, I was only doing the work I’d like to do… both preservation and history.”

There’s much more work to do in the Angkor Wat as they try to limit the weathering by mitigating mold, replacing old stones, and removing vegetation. Along with the physical work on the structure, he wanted young Cambodians to continue learning and discovering their culture and identity.

“How much progress people [may have economically], the feeling of happiness and peace of mind and heart is [what’s] very important. Studying your history and your culture, learning about your identity – that provides you the peace of mind and serenity of heart,” he said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.