SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Part 1 of 3

MANILA, Philippines – On Saturday, September 3, 2016, the day after the Davao bombing, at least one anonymous Facebook account began to share a March 26, 2016 Rappler story, “Man with bomb nabbed at Davao checkpoint.”

It was quickly picked up and shared by Facebook political advocacy pages for President Rodrigo Duterte. Other websites took the entire dated story and reposted on their sites, like newstrendph.com, which is linked to Duterte News Global (the post has since been taken down). Other Facebook pages, such as Digong Duterte and Duterte Warrior, became active participants in this disinformation campaign. Soon after, these pages manually altered their times of postings.

This is disinformation because it led readers to think the man with the bomb was captured that day, September 3, when President Duterte declared a state of lawlessness in the aftermath of the bombing. Readers were duped into sharing a lie because the context changed the old headline.

That lie served a dual purpose: it led you to believe the government’s draconian measure was justified and that it acted just in the nick of time; but, it also hit the credibility of a trusted news source – which was the way these pages represented the story once Rappler alerted our community about it.

It was such an effective campaign that despite the developing news about the Davao bombing, this old story trended number 1 and stayed in the top 10 stories in Rappler for more than 48 hours.

Take another example: a post by Peter Tiu Lavina, Duterte’s campaign spokesman, who attacked critics of the government’s “war on drugs” with his statement about a 9-year-old girl who was raped and murdered.

The photo was taken in Brazil, not the Philippines.

These are only some of the many disinformation campaigns we’ve seen since the election period: social media campaigns meant to shape public opinion, tear down reputations, and cripple traditional media institutions.

This strategy of “death by a thousand cuts” uses the strength of the internet and exploits the algorithms that power social media to sow confusion and doubt.

This series takes apart this new phenomenon triggered by technology and information’s exponential growth:

Part 1 looks at the paid propaganda taking over social media;

Part 2 takes apart the new information ecosystem, its impact on human behavior, and how its weaknesses could be exploited; and,

Part 3 focuses on 26 fake accounts on Facebook, which together extend to a network that influences at least 3 million other accounts.

Weaponizing the internet

It’s a strategy of “death by a thousand cuts” – a chipping away at facts, using half-truths that fabricate an alternative reality by merging the power of bots and fake accounts on social media to manipulate real people.

A bot is a program written to give an automated response to posts on social media, creating the perception that there’s a tidal wave of public opinion. Since this is machine-driven, it can manufacture thousands of posts per minute.

A fake account is a manufactured online identity, sometimes known as a troll depending on the account’s behavior. Not all trolls are part of a paid propaganda campaign, but for now let’s focus on the paid initiatives, which can pay a troll up to P100,000/month.

Often, dozens of these fake accounts work together along with anonymous pages, strengthening each other’s reach for Facebook’s algorithms. These networks can work with or without bots.

A small group of 3 operators, a source tells Rappler, can earn as much as P5 million a month.

Because they often disregard truth and manipulate emotions, these networks easily game Facebook’s algorithm.

In the Philippines and around the world, political advocacy pages, made specifically for Facebook, are cleverly positioned and engineered to take over your news feed.

That allows these propaganda accounts to create a social movement that is widening the cracks in Philippine society by exploiting economic, regional, and political divides.

It unleashed a flood of anger against Duterte critics that has created a chilling effect.

“It was specifically brought into sharp relief during these past elections, where the amount of hatred and vitriol on the internet was just intolerable,” Vince Lazatin, Executive Director of Transparency & Accountability Network, said during a recent panel on Technology and the Public Debate. “It silenced people into submission. The trolls have found a way to weaponize the internet.”

It’s not clear whether these accounts used for the campaign are working with official government channels today.

What is clear is they share the same key message: a fanatic defense of Duterte, who’s portrayed as the father of the nation deserving the support of all Filipinos.

This possible consolidation of the Duterte campaign machinery with state communications channels is dangerous.

We only need to look to China, which fakes nearly 450 million social media comments a year, according to the Washington Post.

This is the first time this sophisticated political propaganda machinery has been used in the Philippines.

FUD – Fear, uncertainty, doubt

Yet, this isn’t the first time social media has been used to manipulate public opinion here.

The first groups to actively use the power of social media, including its dark side tactics, were corporations and their allies. They used a strategy popularized in the computer industry in the US known as FUD – which stands for Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt – a disinformation strategy that spreads negative or false information to fuel fear.

FUD is commonly used in sales, marketing, public relations – and now – politics and propaganda.

As early as October 5, 2014, Rappler alerted the public about how interest groups are mobilizing fictitious social media resources at scale to disrupt online conversations.

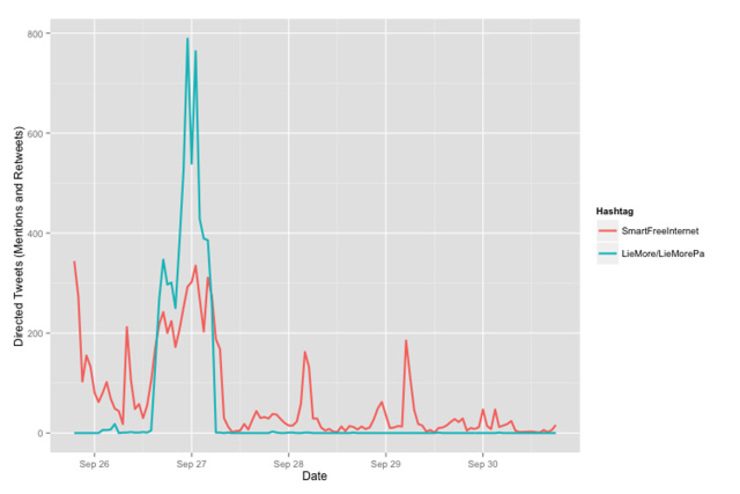

Here’s an example of a black ops campaign on Twitter.

It used a combination of bots and fake accounts to essentially take over and shut down telco promotional campaign #SmartFreeInternet.

In a nutshell, if you use the hashtag, it signals a bot to message your account – to sow fear and doubt to trigger anger – a classic FUD campaign. That’s coupled with fake accounts which continue the campaign. (The greenish-blue line are bots, which attacked at such a high frequency that it effectively shut down the red Smart campaign.)

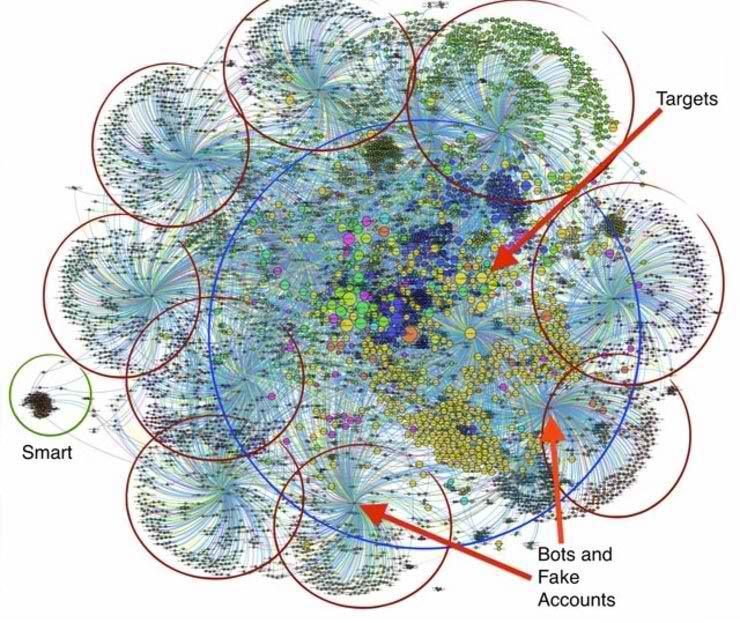

Here’s a map of the conversation, laying bare a familiar communist strategy: “surround the city from the countryside” – effectively shutting out the Smart Twitter account from its targeted millenials.

First social media elections

Social media came of age for politics during the election campaign for the May 2016 elections.

Long before Duterte decided to run, we had long noticed that Davao City had one of the most engaged social media community in the Philippines.

Now we would see humans augmented by machines in both engagement and online polls.

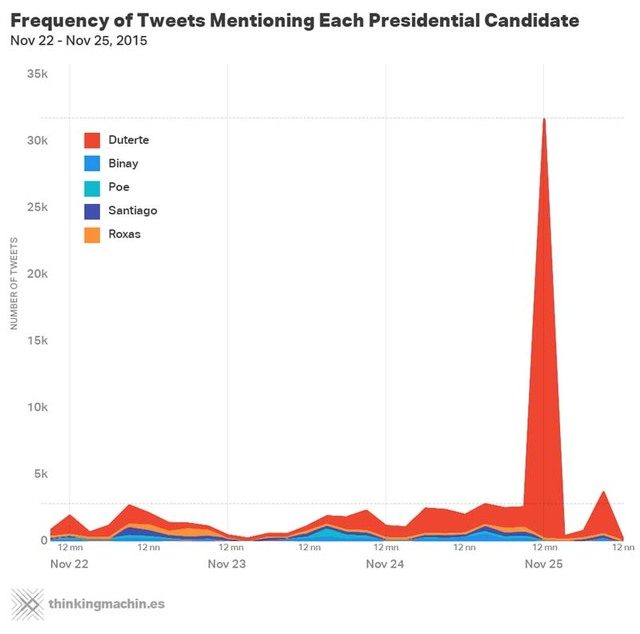

The first time we saw Twitter bots in politics seemed to happen by accident.

Four days after he declared his presidency, from midnight to 2am on November 25, 2015, more than 30,000 tweets mentioning Rodrigo Duterte were posted, at times reaching more than 700 tweets per minute. That’s more than the number of tweets posted when he declared he would run, and more than all the tweets about any presidential candidate over the previous 29 days.

Thinking Machines did an analysis of the campaign using bots and discovered that politics had intersected with entertainment. An examination of the bot-like Twitter accounts showed their timelines full of KathNiel. (Read: KathNiel, Twitter bots, polls: Quality, not just buzz)

What about online surveys which are used to gauge public opinion? Machines can influence that as well.

In December, 2015, Rappler investigated technical manipulation of our online survey, and discovered that 99% of votes from Russia, Korea and China were for Mar Roxas (although there was a small number of these manufactured votes for Duterte as well). Deleting the fake votes changed the winner from Roxas to Duterte. (Read: Who gamed the Rappler election poll?)

Duterte social media campaign

Social media was a crucial factor in electing this president.

Former activist and ex-ABS-CBN sales chief Nic Gabunada headed Duterte’s social media efforts. He told Rappler in a May 31 interview that he built the network with P10 million and up to 500 volunteers, who tapped their own networks.

They were organized into 4 main groups: OFWs or overseas Filipino workers, Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao. He said each volunteer handled between 300 to 6,000 members, but that the largest group had 800,000 members. (Read: Duterte’s P10Msocial media campaign: Organic, volunteer-drive)

It was a decentralized campaign: each group created its own content, but the campaign narrative and key daily messages were centrally determined and cascaded for execution. Gabunada emphasized these posts were done by real people, not bots.

Analysts agreed that the 2016 elections were the most engaged in Philippine history, but they also pointed out that the period also highlighted some of the angriest and vicious political discourse that’s transforming our democracy.

By March, two students at UP Los Baños had been threatened by an online mob.

In a scene reminiscent of the Boston bombing witch hunt, Duterte supporters tracked cell phone numbers and harassed and threatened the students they perceived to be disrespectful of Duterte.

At one point, they created a Facebook page demanding death for the student it named. (READ: #AnimatED: Online mob creates social media wasteland)

Within 48 hours, the Duterte camp asked his supporters to “take the moral high ground” online. (READ: Duterte to supporters: Be civil, intelligent, decent, compassionate)

In April, a young woman who posted she was campaigning against Duterte was deluged with threats and harassment. (READ: ‘Sana ma-rape ka’: Netizens bully anti-Duterte voter)

Shortly before election day, she tested laws governing cyberbullying by filing 34 complaints in court.

Boycott & attack media

The day after he won, Duterte called for healing and his campaign team supported and trended his message using the hashtag #HealingStartsNow.

It didn’t last long.

The soon-to-be president made numerous controversial statements in late night press conferences, including what could be seen as a justification for journalist killings and his wolf-whistle of a GMA7 reporter.

By the beginning of June, Duterte announced he would boycott media and channeled all statements and press conferences through state television network, PTV, and RTVM.

He didn’t break that boycott of private media until August 1.

In those two months, the campaign machinery pivoted to propaganda and threats, first attacking ABS-CBN, then Inquirer (largely because of its Kill List keeping track of extrajudicial killings).

GMA7 and Rappler took the hot seat after Duterte wolf-whistled at a GMA7 reporter, Mariz Umali, at a press conference, and Rappler reporter Pia Ranada-Robles questioned him on it.

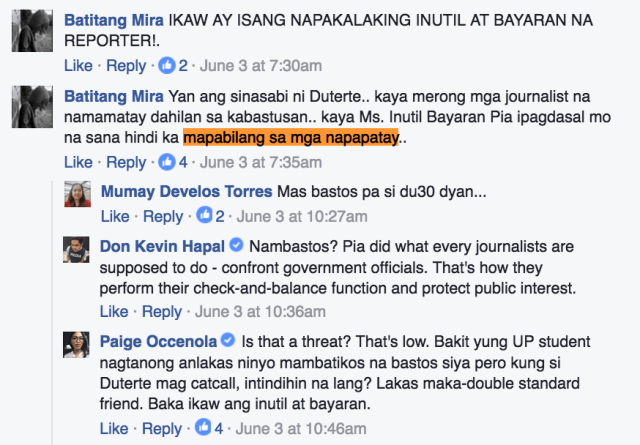

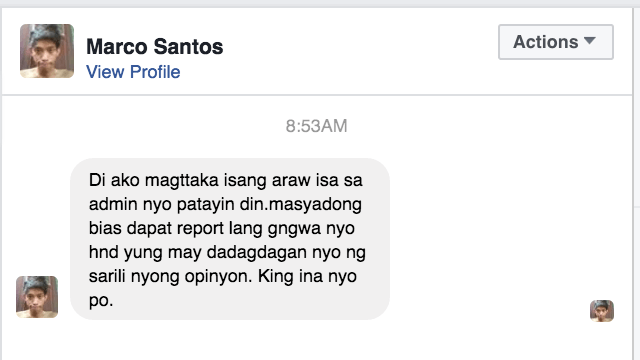

The social media attacks were vicious and personal. They built on their campaign messages, continuing to rail against the Liberal Party and building fear for a “yellow army.”

Anonymous and fake accounts rallied real people to create and spread memes with simple messages that contain a grain of truth, the most efficient for FUD:

- “Bias” – that these media groups are biased against Duterte.

- “Bayaran” – that journalists are paid and corrupt.

- “Oligarchs” – that journalists work for vested interests.

- “Clickbait” – that media groups are commercial interests so they use clickbait headlines for cash.

When the leader of a nation refuses direct access to journalists, controls the narrative top down through established state groups, and is echoed bottom up by social media initiatives, it creates a chilling effect on 2 fronts:

- Access becomes a personal favor for reporters, removing a professional environment and creating a more feudal landscape. Reporters, if they want access, think twice about questioning power.

- Critical posts on social media are immediately attacked, forcing “normal” people to leave the conversation. Many close their Facebook accounts, leaving the field open for more sophisticated manipulation in an increasingly growing echo chamber.

On September 19, the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines called on the government to investigate social media attacks against journalists Gretchen Malalad and Jamela Alindogan-Caudron.

On September 22, President Duterte asked his supporters to stop threatening journalists.

But his statement has done little to stem the propaganda attacks.

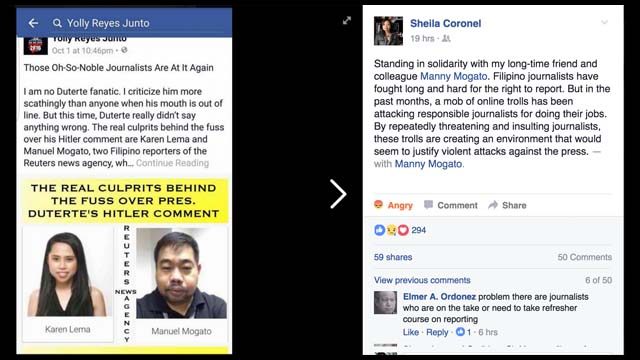

Over the weekend, Reuters reporters Manny Mogato and Karen Lema were targeted after reporting President Duterte’s remarks about Hitler.

Shape perception, rewrite history

These all impact public perception. Fallacious reasoning, leaps in logic, poisoning the well – these are only some of the propaganda techniques that have helped shift public opinion on key issues.

Take for example what was once a prevailing acceptance of human rights and the idea of “innocent until proven guilty.” Today there seems to be a wide acceptance of murder, especially of drug pushers, and any attempt to question that is portrayed as part of a conspiracy theory.

It’s part of the reason many silently accept that in just 11 weeks, 3,546 people have died in the government’s “war on drugs.” (These figures from the PNP were later revised to 3,145 on September 14, 2016).

After all, when someone criticizes the police or government on Facebook, immediate attacks are posted, including “someone should rape your daughter,” “how many people were raped by pushers,” “why not talk about those killed by drugs,” “mayaman kasi kayo,” and many more.

Could it also be used to rewrite history?

That was the charge against the Official Gazette on the 99th birthday of Ferdinand Marcos, who held power for nearly 21 years.

Using a quote that subtly links Marcos to Duterte’s campaign for change, the caption’s revisions sparked outrage, especially after a conflict of interest surfaced: it was posted by a former Marcos staff member.

So what can be done?

Understanding what’s happening is a first step.

Working together to separate fact from fiction is another step.

Regardless of your political leaning, social media is a powerful tool, and if abused, the first casualty is the truth – which will have a direct impact on the quality of Philippine democracy. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.