SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

(Part 1 of 2)

MANILA, Philippines – It only takes a glance at Metro Manila’s major thoroughfare to know how bad traffic is in the Philippines’ national capital region.

Rush hour or not, EDSA seems perpetually stuck in a state of congestion. Cars crawl along the 23.9-km highway and easily spend at least an hour in non-moving traffic. Commuters spill out onto the streets, fighting each other for standing-room space in crowded buses. Overhead, one of the metro’s train lines chug along dilapidated rails, carrying twice its maximum capacity. It’s considered a good day for commuters if the train doesn’t suffer yet another technical glitch.

This is what Metro Manila looks like today – home to a daytime population of 15 million, a car-centric urban environment where motorized vehicles dominate the roads, and public transport system that is neither efficient nor organized. The worsening traffic problem is troubling for an economy hailed as one of the fastest growing in the Asian region, and especially considering that the Philippines, in 2010, was part of the regional bloc that committed to establish a sustainable, energy efficient, and environmentally-friendly transport system.

The Philippines, the second most populous country in Southeast Asia, faces a serious transportation problem. Nearly 50% of its 88 million people live in urban areas, creating a challenge for policymakers to ensure citizens’ quality of life.

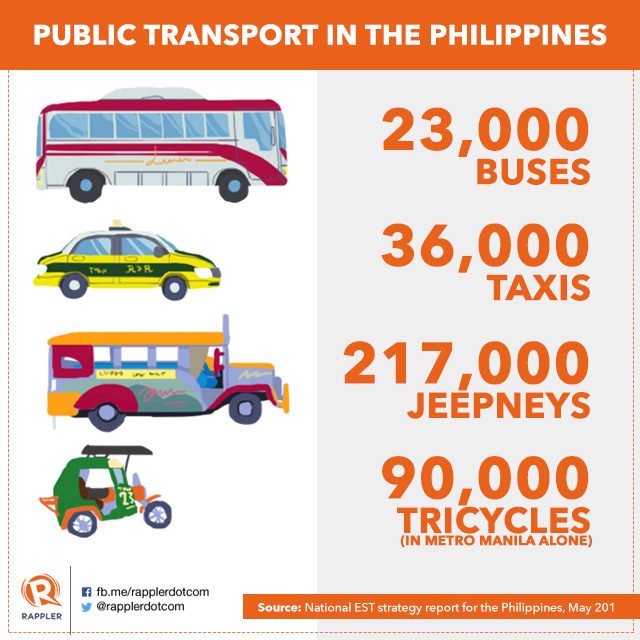

In Metro Manila alone, travel by public transport accounts for 69% of the total number of trips taken every day, with buses and jeeps accounting for 71% of these trips, according to a study by the Japan International Cooperation Agency.

But limited road network and an increasing number of private vehicles have exacerbated road congestion. It is also contributing to bigger carbon dioxide emissions. In the Philippines, the transport sector accounts for 36.1% of the total carbon dioxide emissions from fuel combustion.

In 2010, member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) adopted a region-wide strategic transport plan that aims to arrest the negative effects of the increase of motorized vehicles: the ASEAN Strategic Transport Action Plan (ASTP) 2011-2015, also known as the Brunei Action Plan.

The ASTP aims to establish an integrated and sustainable transport network that can help promote trade and tourism within the region. It also recognized the need to create safe, efficient, and environmentally-friendly transport corridors. With transportation accounting for more than 20% of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions, the ASTP wanted ASEAN member states to share knowledge on sustainable transport projects and to pilot-test them in their own countries.

One of the key thrusts of the ASTP is promoting public transportation. With the exception of Singapore, many major ASEAN cities are struggling to improve public transport and to increase the number of citizens who take mass transit.

The ASTP’s recommendation: for ASEAN countries to study the feasibility of setting up a bus rapid transit (BRT) system, which it considered to be “cheaper, faster to construct, more profitable to operate, and economical to commuters” compared to rail-based systems.

The ASTP also highlighted the need to promote alternative mobility by providing sidewalks and bike lanes to encourage walking and cycling for short distance travels.

The Philippines’ national strategy

In recent years, the Philippines’ Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC) has been laying out plans to improve public transportation networks, promote alternative mobility options, and cleaner transport through alternative fuels and green vehicles.

In 2011, a national environmentally sustainable transport (EST) strategy was released to guide the development and implementation of a master plan for the country’s transportation system.

This EST strategy envisions an integrated, efficient, and effective transport system that moves more people through low-emission transport modes and reducing the emission of greenhouse gases.

Under the national EST strategy, the government should shift to non-motorized forms of transport (such as walking and biking) and an improved public transportation system (such as BRT, and an expanded urban rail system).

It also aims to improve existing transportation modes, such as setting up intelligent transport systems, improving vehicle inspection and maintenance, and shifting to cleaner fuels.

How far has the Philippines gone in achieving the aims of the national EST strategy?

Improving buses and BRT share

With transport-related emissions expected to increase by 57% worldwide between 2005 to 2030, and as the Asian region undergoes rapid urbanization, the Philippines recognizes that “any serious reform” in the transport sector will have to include major changes in current existing systems.

Policymakers are shifting to the idea that the goal is to move more people instead of moving more cars. One cause of traffic congestion is the oversupply of private vehicles crowding limited road space.

The DOTC believes that one solution to address this is to take private cars off the roads and get car owners to take mass transit instead. The rationale: private cars carry only around 3 or 4 passengers, as opposed to buses which take up more road space yet carry 60 or more passengers.

But to entice car owners to take the bus, the DOTC has to convince them that bus travel is cheaper, convenient, and faster than using private cars. In recent months, the department has introduced the express bus and the point-to-point bus systems.

Unlike ordinary city buses, these buses make limited or no stops at all between origin and destination, shaving off an estimated 30 minutes of travel time. The fares may be more expensive than that of regular city buses, but, the DOTC reasons, it’s still cheaper compared to paying for gas and parking.

Why overhaul the bus system? It’s a low-cost solution that makes use of what Metro Manila already has in abundance. It’s a strategy adopted from South Korea’s successful bus reform program, a project that involved transport planning expert Gyeng Chul Kim, now also an adviser for the DOTC.

Overhauling the bus system also involves the challenge of managing supply and demand: matching the number of buses deployed on the road with the number of passengers needing them. To achieve this, a public transport information management center will be set up within the year to track buses using GPS.

The DOTC is going a step further and following a specific recommendation of the ASTP: setting up the BRT system. With funding help from the World Bank, the country’s first-ever BRT project is expected to be operational in Cebu City by 2018. The project, approved in 2014, is expected to answer the transportation needs of the 2.5 million people living in Metro Cebu.

Metro Manila is also set to have its own BRT systems, with one line running along the length of EDSA, and a 12.3-kilometer line running from Manila to Quezon Avenue.

Promoting alternative mobility

Transport experts and urban planners have lamented how less than 2% of Filipinos own cars – and yet, most of the roads are dedicated to vehicles.

Even the design of roads confirm how car-centric Metro Manila is. Sidewalks are very narrow or non-existent, and pedestrians frequently spill out onto the road. Cyclists weave in and out of traffic, and most motorists don’t acknowledge the presence of bike lanes – if they are present at all.

The challenge for government officials is to promote a culture of cycling and walking, and one way that other countries have tackled this problem is by investing in the appropriate infrastructure. Build it and they will come: by providing ample sidewalks, and bike lanes, the public will be encouraged to walk or cycle instead of taking a car ride, especially for distances less than 2 kilometers.

Several cities in Metro Manila have adopted this tactic as their way to contribute to the country’s green initiatives. Transport experts, for instance, have lauded Makati’s network of pedestrian walkways, making it easy to go around the busy central business district by walking.

Marikina City is best known as a cyclist-friendly haven, notable for its extensive 52-kilometer bikeway network, which was launched in 2001 through a a $1.3-million grant from the World Bank’s Global Environment Facility.

Pasig City also has its carless Sundays, turning a stretch of road in the Ortigas business district into a bike-friendly, pedestrian-friendly zone. The city government has also partnered with Clean Air Asia and the Asian Development Bank to host a bicycle-sharing network in the city.

Meanwhile, the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority – the metro body tasked to manage traffic in the capital region – has also set up bike lanes along EDSA and launched its own bike-sharing programs.

Outside of Metro Manila, the city of Vigan in Ilocos Region and Iloilo in Western Visayas have also made pedestrian-friendly spaces part of the city landscape.

The Spanish-influenced Vigan, for instance, is working to preserve its rich heritage and culture by keeping the historic cobblestone street Calle Crisologo free of motorized vehicles.

In Iloilo City, its 1.2-kilometer riverside Esplanade – originally intended to be yet another road – is now a public park that provides breathing space for locals, and also serves as a pedestrian link between two bridges.

To encourage a mindset of walking and cycling for Filipinos, several environment advocates have pushed for more road-sharing activities. The experiments have been piloted in 2011 in Cebu City, where half of the roads were set aside for the exclusive use of pedestrians and cyclists.

While these were not a resounding success – several motorists complained of the heavy traffic triggered by road closures – advocates believe that refining the experiments and keeping up the momentum will be key to eventually creating more livable cities.

Moves in the legislature

One of the latest moves to further strengthen the national EST framework is a proposed measure filed in Congress in 2015. House Bill 6059, or the Sustainable Transportation Act of 2013, seeks to promote efficient and environmentally-friendly modes of transportation and the use of non-motorized vehicles.

The bill, filed in August 2015 by Catanduanes Representative Cesar Sarmiento, envisions a Philippine transport system with adequate walkways and bike paths, modern vehicles that use cleaner fuels, an efficient and environmentally-friendly mass transit system, travel demand management programs, and a transportation plan tied up with land use plans.

More than just a means to help alleviate traffic, the bill recognizes that this kind of transportation system would help save the environment and restore the dignity of the Filipino commuter.

The bill seeks to mandate government agencies to craft sustainable transport action plans, policies to establish emission control standards, infrastructure to encourage walking and biking, and more efficient mass transit systems.

While the DOTC is designated as the lead implementing agency, it is expected to coordinate with other agencies and local government units in the implementation.

This is crucial because the DOTC alone cannot undertake an overhaul of the transportation system. It can, for instance, set guidelines for the creation of pedestrian lanes and bike lanes, but it is the role of LGUs to drill down to the specifics – providing the actual road infrastructure, making sure that these lanes are kept for the exclusive use of pedestrians and cyclists, and mandating business owners to put up bicycle parking spaces.

In promoting cleaner fuels and assessing health impact, the DOTC should coordinate with the health department, environment department, and energy department.

It is also expected to consult other stakeholders, such as civil society groups and the business sector, in studying the feasibility of travel demand management programs such as carpooling, telecommuting, and congestion pricing.

The bill also zeroes in on the role played by local government units. Aside from their involvement in the implementation, LGUs are required to submit an integrated land use and transportation plan that will include ways to avoid unnecessary travel.

The proposed measure recognizes the crucial link between a transportation plan and land use planning. Emphasis is placed on transit-oriented development, or mixed-use residential and commercial areas, that are easily accessible to public transportation system and alternative mobility options.

While it has promising points, the bill remains pending with the House committee on transportation as of September 2015. A technical working group has been created by the House committee on transportation to consolidate 5 bills related to the issue.

More programs needed

While the Philippines’ focus on improving public transportation is a step in the right direction, much more needs to be done in the area of encouraging alternate mobility options and other forms of non-motorized transportation (NMT).

A 2009 study by academics Brian Gozun and Marie Danielle Guillen noted that trips less than 2 kilometers could be covered by walking or cycling, but the lack of “hard” and “soft” infrastructure – bike lanes, for instance, and policies that support these modes of transport – can affect the public’s willingness to walk or cycle.

For Alvin Mejia, transport program manager of Clean Air Asia, providing the right support can entice citizens to walk or bike more.

“I think that the general stigma against cycling in society is an issue of the design of our cities, as well as our popular media giving a premium to having faster and bigger vehicles,” he said.

“This has degraded cycling into an inferior mode of transport which should not be the case. Cyclists, as well as pedestrians, should be entitled to the same privilege as the, other motorized road-users,” he added.

According to Gozun and Guillen, an integrated NMT policy should consider information campaigns to promote alternative mobility, the development of walkways, bike racks, and bike rental programs, and walk-friendly designs in land use plans.

Another Filipino form of NMT – the pedicab – can also be more thoroughly studied to determine how it can be effectively integrated in existing road designs that favor motor vehicles. While some see it as a detriment and even a contributor to traffic, it can work in specific areas where traffic volume is not too high.

The Philippines can also look into expanding bike-sharing schemes as a way to introduce cycling and make it a more acceptable concept for the everyday Filipino.

“Bike-sharing schemes can ultimately be acceptable once people realize that they can fill certain voids in the transport system here in Metro Manila. For such schemes to be successful, the people need to see that such schemes are useful, safe, save money, and save time,” Mejia said.

To speed up the wider adoption of such a scheme, Mejia suggested setting up a bike-sharing network with access to critical origin and destination points and integration with other modes of transport.

The network should also be equipped with technological systems that can monitor users’ activities and provide real-time information on the availability of bikes and docks. These will provide baseline data to further improve the system, he said.

“Sustainable transportation projects to ease traffic congestion and reduce emissions are now high on the public agenda, and putting dedicated bike lanes and developing bike-sharing schemes across cities should complement the existing and planned transport services,” Mejia said.

He added, “Long-term sustainability would require transforming the way we build our cities and integrating cycling, as well as walking, into our transport planning processes.” – Rappler.com

The research for this report was supported by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.