SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

From the time President Duterte won the 2016 elections, workers throughout the country waited for the fulfillment of his campaign promise to end “endo”.

The main agency in charge of this, the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) headed by Secretary Silvestre Bello III, spent several months vacillating on the issue on the pretense of implementing a triple-pronged approach at addressing the evils of contractual employment (usually referred to its Filipino slang, “endo” or end-of-contract).

DOLE’s dilly-dallying is in stark contrast to the President’s consistent and unequivocal stand against contractualization.

In the end, DOLE chose to break the President’s promise and keep “endo” alive. (READ: ‘Legal’ contractualization still allowed in new DOLE order)

When Secretary Bello finally signed Department Order (DO) No. 174 (2017), he did not end “endo.” On the contrary, he ensured its continued practice and prevalence. Workers now are worse off than ever before because DO 174 merely continues DOLE’s failed policies to regulate contracting out of labor.

To see this fully, one properly begins with an overview of the law on contracting and the policies which the DOLE has toyed with through the years.

What the law says

Articles 106 to 109 of the Labor Code remain to be the main law on employment relationships which involve 3 parties, namely, a Principal which farms out work, a Contractor or Subcontractor which accepts the responsibility to do the work and the Worker(s) who actually do the work.

Recognizing that this so–called trilateral arrangement leaves workers vulnerable to abuse, the law explicitly prohibits what it labels as “labor only” contracting.

This exists when “the person supplying workers to an employer does not have substantial capital or investment in the form of tools, equipment, machineries, work premises, among others, and the workers recruited and placed by such person are performing activities which are directly related to the principal business of such employer.”

To ensure that the workers know who their true employer is, the law says that under prohibited labor-only schemes, the principal shall be responsible to the workers as if they were directly employed by him/her/it. The contractor or subcontractor is treated merely as an agent or no different from the Principal. (READ: No ‘endo’ in 2017? Challenge of ending labor contractualization)

Fake news: DOLE cannot prohibit contracting

It is very important to know that the Labor Code gave more than sufficient authority to the Secretary of Labor and Employment to address whatever abuse workers face under contracting arrangements.

In very clear terms, Article 106 of the Labor Code says: “The Secretary of Labor and Employment may, by appropriate regulations, restrict or prohibit the contracting-out of labor to protect the rights of workers established under this Code.”

Therefore, the repeated assertion by DOLE officials that they cannot prohibit contracting out of labor is simply not true.

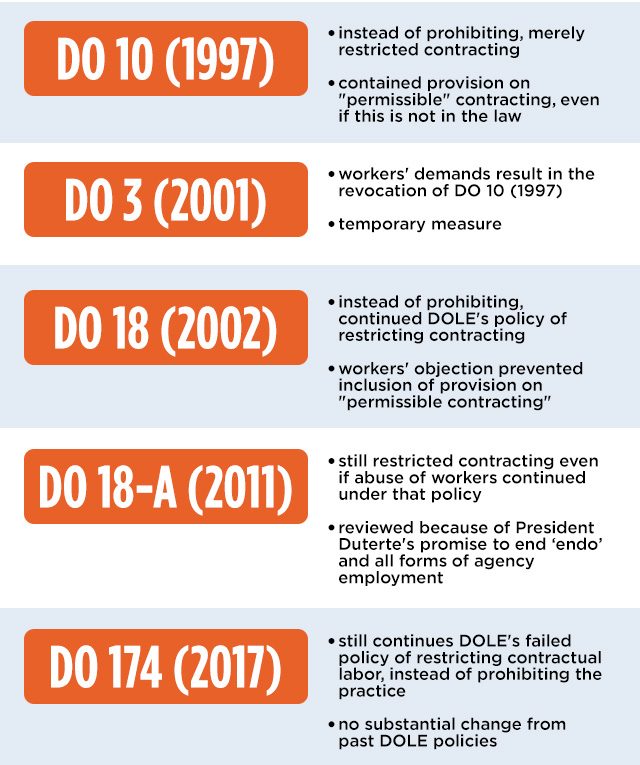

Indeed, for more than 20 years, the DOLE has adopted the weak approach and has chosen to restrict contracting arrangements instead of prohibiting it. In those many years, DOLE’s approach has been demonstrated to be a complete failure.

D.O. 10 (1997)

In May 1997, then Secretary Leonardo Quisumbing issued Department Order No. 10 (D.O. 10). It was the expressed aim of DOLE to give employers the “flexibility” they wanted while guarding workers’ rights. Significantly, D.O. 10 included a provision which introduced the concept of “permissible contracting or subcontracting.”

This lax approach under D.O. 10 led to an upsurge of employment through agencies. It also led to a proliferation of short-term and precarious employment arrangements. As a result, countless positions which had previously been occupied by directly-hired regular employees were given to workers hired by agencies. (Insert Figure 2)

In time, society naturally developed colloquial names for its workers’ common experience of insecurity in employment. “End of contract” is “endo,” indirect employees introduced themselves as “agency po ako,” and repeated employment lasting five months is “5-5-5”.

Through time, agency-hired and “endo” workers internalized the practice that they were worth and treated less than regular workers.

They accepted its impact on their pay, the unavailability of overtime and holiday pay, rest day premium, leaves, and many other basic conditions of work. Their ID’s and uniforms are constant reminders of their lesser status. And of course, forming or joining a union means losing one’s job.

The evil in trilateral arrangements

The main evil in the agency arrangement lies in the Principal’s inherent ability to end its contract with the Contractor/Subcontractor and in the ease by which the contractor can pull out the worker from work and place her/her in a “floating” status.

When this happens – as it does for a wide range of reasons – the employee loses the source of her/his livelihood. The evil is so pernicious that the threat alone of losing one’s job is enough to render contracted workers impotent against abuse.

Thus, where agency-hired workers wish to enhance the terms and conditions of their employment, they can act only at the cost of their very livelihood. For agency-hired workers, keeping the job – despite poor employment conditions – is still better than losing it altogether.

In this way, the threat of losing one’s job naturally leads to a workers’ inability to enforce their rights.

While the best way for workers to fight for their rights is to form or join unions, this too becomes impossible for them. Just a rumor that workers are engaged in union activities is sufficient to cost them their jobs.

Ask yourself: have you seen any service contractor or agency which is unionized? This is the way by which a cycle is formed which keeps workers trapped in short-term, abusive employment relationships.

DOLE insists on failed policy

The proliferation of worker abuse under DO 10 (1997) was the principal reason why workers demanded its repeal right after President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo assumed the presidency in 2001. Thus, in May 2001, then Labor Secretary Patricia Sto. Tomas issued DO 3 (2001), which revoked DO 10.

Designed as a temporary measure, DO 3 merely paved the way for a new set of guidelines on contracting and subcontracting.

On February 2002, Secretary Sto. Tomas issued Department Order 18 series of 2002. Due to workers’ objection to any “permissible contracting,” DO 18 did not include any provision on “permissible contracting.”

However, it is important to know that DO 18 merely continued DOLE’s policy to restrict – not prohibit – contracting-out of labor.

As a result, regular employment continued to dwindle and a whole industry of “service contracting” blossomed. The evils of DO 10 returned with a vengeance, with employers evolving new ways to prevent workers from attaining regular status. Many agencies were seen to disguise themselves as “cooperatives” which prevents unionization and further confuses the availability of workers’ right to wages and basic conditions of work.

Shortly after the long incumbency of President Arroyo gave way to President Benigno Aquino III, DO 18 was replaced by DO 18-A (2011).

“Permissible Contracting” remained excluded but DOLE continued to insist on its failed policy to merely restrict contracting out of labor. It still refused to exercise its authority under the Labor Code to prohibit it.

In the more than 2 decades in which the DOLE has insisted on restricting and regulating the practice of contracting out of labor, regular employment has now become the exception.

In its stead, non-regular work including hiring through agencies, is now the norm. One only has to ask the person delivering food to your homes and offices, the salesperson showing you shoes at the department store, or the technician repairing your telephone or internet or cable TV connection.

Less visible, workers in factories and manufacturing plants are also now a mix of regular and agency hired workers with the latter outnumbering the former in many cases.

And so, presently, the cycle described above continues and workers remain unable to enforce their rights or form and join organizations for their protection.

Ultimately, the continued proliferation of employment arrangements which render workers vulnerable to abuse is directly related to the DOLE’s insistence on its failed policy of merely restricting contracted labor instead of prohibiting it.

Through more than 20 years, the DOLE has implemented the same weak approach while promising to finally protect workers from abuse.

To paraphrase an oft-heard quote, it is crazy to keep on doing the same thing over and over, but expect a different result.

Cosmetic change

After the elections, workers demanded the fulfillment of President Duterte’s commitment to end endo and employment through agencies.

With one voice, they told DOLE to change its policy of merely restricting the practice of contracting out labor and, for once, exercise its authority under the Labor Code to prohibit it.

Sadly, however, DOLE chose not to listen to the workers. Instead, DO 174, signed on March 16, 2017, continues the same failed policy of regulating what is now an industry of Brobdingnagian proportions.

Contrary to DOLE’s media posturings, the latest order only contains cosmetic changes or amendments too inconsequential to benefit workers. According to the DOLE, contractors must now have capital of at least P5 million instead of the previous P3 million. However, years of business success has seen the contracting industry grow into a multi-billion peso industry. The increased in capitalization is therefore of any doubtful efficacy.

On the other hand, consider the following troubling aspects of DO 174:

- D.O. 174 continues to allow principals to hire workers through agencies. This, despite our long history which proves that under such tripartite arrangements, workers are extremely vulnerable to abuse. The prohibitions it contains – such as labor only contracting – have been prohibited for the past 2 decades. And yet, the abuse of workers have only worsened. So the question has to be asked: what has changed with D.O. 174?

- Even worse, D.O. 174 inexplicably re-introduces a provision on “permissible contracting.” This provision has already been rejected many times over since its first incarnation in D.O. 10 (1997) because it only encouraged employers to contract out labor and gave agencies a mask of legitimacy to hide behind. And yet, the DOLE, defying logic and good sense, revives it in D.O. 174. One will be challenged to find something more idiotic!

- In the rounds of consultations it conducted, DOLE received many testimonies from workers about the abuse of the concept of “cooperatives.” And yet, D.O. 174 completely ignored them and chose instead to prohibit only those which it considers to be “in-house” cooperatives. By doing this, DOLE allows all other cooperatives to engage in contracting and subcontracting – a practice which have demonstrably misled many workers regarding their true status of employment and blunted their ability to exercise their rights as employees.

- D.O. 174 removed the ability of workers’ representatives (bargaining agents) to demand a copy of the service contract between the principal and the contractor/subcontractor. This was previously granted by D.O. 18-A but was inexplicably removed in D.O. 174, leaving workers and their unions even weaker than before.

- D.O. 18-A previously required contractors to set at least 10% of the total contract cost as the standard administrative fee. Competition among contractors should then operate above this rate. This is not anymore required by D.O 174. Thus, one can only wonder how the DOLE expects contractors, without a set minimum for such a fee, to avoid cutthroat pricing and racing to the bottom with regard rates charged to principals. These practices have invariably lead to the denial of workers’ benefits.

Statements made by the DOLE following the issuance of D.O. 174 seem to indicate a pledge to enforce labor laws in order to protect workers.

However, given the DOLE’s betrayal of the President’s promise to end “endo” and employment through agencies, the DOLE has clearly shown its choice to cling to its failed policy of regulating contracting out of labor in face of workers’ unanimous demand to prohibit it.

This indicates a readiness to accommodate employers’ interests at the cost of workers’ rights and welfare. What kind of enforcement then can we then expect from such a Department?

As workers and workers’ organizations such as NAGKAISA and SENTRO continue to demand for the total prohibition of all forms of contracting, they also remain vigilant in guarding the rights of workers: the person delivering your food, the salesperson offering you shoes, the factory worker producing goods. Will they finally enjoy the security of tenure, the living wage, the right to form and join unions, and all other rights guaranteed by the Constitution?

Under a DOLE which continues to insist on a weak and failed approach to contracting out of labor, it is highly unlikely. And the workers’ demand to prohibit all forms of contractualization will only grow louder. – Rappler.com

SENTRO is a national labor center composed of 16 industry federations and sectoral organizations. It has been at the forefront of the fight for security tenure for many years. It is an affiliate of the NAGKAISA Labor Coalition.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[In This Economy] Is the Philippines quietly getting richer?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/20240426-Philippines-quietly-getting-richer.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=194px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[In This Economy] A counter-rejoinder in the economic charter change debate](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/TL-counter-rejoinder-apr-20-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=267px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Vantage Point] Joey Salceda says 8% GDP growth attainable](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-salceda-gdp-growth-04192024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[ANALYSIS] A new advocacy in race to financial literacy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/advocacy-race-financial-literacy-April-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.