SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

“My land is half an hour’s walk from the sea. The whole place is poetic and very picturesque…without comparison. At some points, it is wide like the Pasig River and clear like the Pansol [in Laguna], and has some crocodiles in some parts. There are dalag (fish) and pako (edible fern). If you and our parents come, I am going to build a large house where we can all live together.” – Jose Rizal in a letter to his sister Trinidad, January 15, 1896

ZAMBOANGA DEL NORTE, Philippines – More than a century ago, Jose Rizal bought a 16-hectare land in “Barrio Talisay” here, which became his home for most of his four years of exile, and the site of his school for young Dapitanons and his agriculture development area. In this property, he also built his eye clinic, his students’ dormitory, and even a small dam for his property’s water system.

However, efforts to preserve the property – now called the Jose Rizal Memorial Protected Landscape (JRMPL) – is confronted by at least three threats:

- Continuing people’s encroachments

- Alleged questionable acts within the local offices of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) that are tasked to protect it

- Government’s ill-thought infrastructure projects

Ronald Gadot, in charge of DENR 9 Regional Executive Director’s office, said he was not aware of wrongdoing within his ranks, but challenged accusers to substantiate their allegations, “and I will deal with these personally.”

The looming problems inside JRMPL are glaring, however.

Rizalistas and other claimants

From a few families in the early 1980s, the number of residents in JRMPL has grown to around 500. A lot of houses made of light materials have been transformed into modern concrete structures. There is even a covered court.

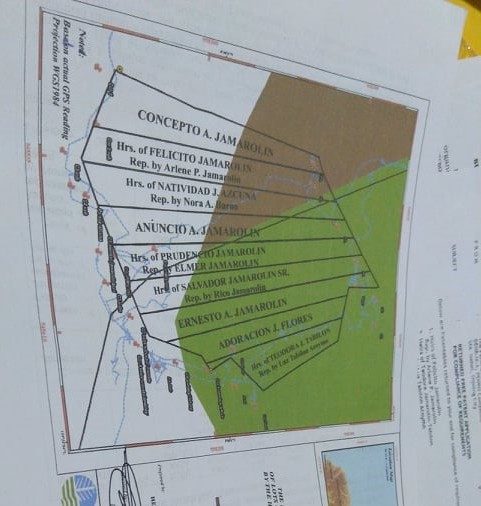

While many of the settlers were given Certificates of Tenure Migrants by DENR, at least four lots inside JRMPL have been issued titles. Nine others in Sitio Pook are in the process of getting titled by descendants of Celestino Acopiado, Rizal’s alalay (handyman), and his wife Anecitas Bael, who was the national hero’s cook.

The claimants said Rizal bequeathed his property to their great-grandparents Celestino and Anecitas Acopiado, but sources within the Community Environment and Natural Resources Office (CENRO) based in Segabe, Municipality of Pinan, the applications were “full of other technical irregularities that could not have been done without the help of DENR officials.”

Meanwhile, Sitio New Jerusalem, also inside JRMPL, is occupied by a group calling themselves “Rizalistas” because they believe that their founder, the late Felimon Reambonanza, was Rizal’s reincarnation.

Elsewhere within the JRMPL are an undetermined number of other occupants.

The provincial government made the situation worse when it built a road across the protected area in 2021 without getting permission from DENR and the Protected Area Management Board (PAMB).

Provincial Engineering Office bulldozers cut down everything on their path, including centuries-old trees, until the PAMB, then under Protected Area Supervisor (PASu) Jaymark Balbosa, intervened and filed a case in court also in 2021.

Recently, however, Dapitan City Prosecutor Lynbert Lo dismissed DENR’s complaint. DENR’s Gadot claimed the dismissal was based on technicalities, and that CENRO-Segabe had re-filed the case against the Zamboanga del Norte provincial government.

Rizal property is protected area

Two months after arriving in Dapitan on July 17, 1892, Rizal bought the abandoned agricultural land in Talisay from Juana Tabugok for P4,000, which he won from Reales Loterias Espanolas de Filipinas (Royal Spanish Lottery in the Philippines).

“My land is half an hour’s walk from the sea. The whole place is poetic and very picturesque…without comparison. At some points, it is wide like Pasig River and clear like Pansol [in Laguna], and has some crocodiles in some parts. There are dalag (fish) and pako (edible fern). If you and our parents come, I am going to build a large house where we can all live together,” Rizal said in a letter to his sister Trinidad on January 15, 1896.

Barely a year after sending that letter, Rizal was executed by firing squad in Bagumbayan (now Luneta), and Spanish authorities confiscated his property in Talisay.

In 1913, a year after the American occupation, Rizal’s property was converted into a public park and, on September 3, 1940, President Manuel Quezon signed Proclamation 616, declaring the 10 out of the original 16 hectares property as “Rizal National Park.”

The proclamation prohibits the “sale, settlement or other dispositions, subject to private rights,” of the property.

On April 23, 2000, then-president Joseph Estrada issued Proclamation 279, declaring the Rizal National Park as a protected area, which had been increased to 439 hectares, with its peripheries as buffer zone.

The proclamation also renamed the area Jose Rizal Memorial Protected Landscape.

And from 439 hectares, JRMPL was further expanded to 474 hectares through Republic Act 11038 or the expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System (NIPAS) signed by President Rodrigo Duterte on June 22, 2018.

Land certificates issued to tenured migrants

Despite the prohibitions on the disposition of the property, a former Dapitan City councilor, who requested not to be named, estimated that the number of residents within JRMPL had grown from a few families to 350 to 500, composed mostly of Rizalistas.

“The occupants grew that much amid the fact that only a handful were descendants of the Acopiado couple, and it would be difficult to ascertain the exact number of occupants because many of them – particularly Rizalistas – move from one place to another,” the source admitted.

In Sitio New Jerusalem alone inside the JRMPL, there are now at least 60 families of Rizalistas residing, and the number continues to grow.

Gadot pointed out, however, that Republic Act 11038 or the expanded NIPAS protects and respects all properties and private rights within JRMPL and its buffer zones that existed five years before and at the time the law was signed.

“We respect the people living there because they are part of the bio-diversity within JRMPL, as long as they do not cause destruction, like cutting of trees or conduct mining activities,” he continued.

Gadot also said that, two years after Duterte’s Republic Act 11038 took effect in 2018, people residing within JRMPL were to be given certificates as tenured migrants. The documents acknowledge their existence in the protected area, although these do not grant them security of tenure.

So far, the DENR has issued 270 Tenured Migrants Certificates to the Rizalistas and other people residing within JRMPL, revealed Salahuddin Kaing, the provincial environment and natural resources officer of Zamboanga del Norte.

‘JRMPL can’t be protected’

“It’s really impossible to effectively protect the entire protected area,” admitted engineer PASu Camilo Arco, successor of Balbosa, saying that he is JRMPL’s only regular employee, assisted by three non-regular employees.

Arco told Rappler that the ideal work force for the 474-hectare JRMPL should be 30 regular employees.

“How can I walk around JRMPL and watch for people sneaking in or cutting trees?” asked Arco, adding that he didn’t even know the exact number of residents within the protected area.

But Gadot argued that Arco’s statement was not accurate because the protection of JRMPL is still the responsibility of the entire CENRO-Segabe and not solely of the PASu.

Nevertheless, Gadot said they already have the “approved plantilla” for JRMPL personnel, “and hopefully it can be funded soon so we can hire more employees.”

Of the seemingly uncontrolled growth of occupants within JRMPL, Arco said, “The government has always tended to favor the people.”

Besides, Rizalistas are also known to have rendered free daily clean-up of the Rizal Park, which is controlled by the equally undermanned National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP).

It was after the Rizalista organization under the name “Kingdom of God” was registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission in 1982 that the late Reambonanza and a few followers started to build their houses inside JRMPL, at the mountain part adjacent to the Rizal Park.

“Actually, we don’t worship Rizal as our God,” said Rio Patangan, a devout Rizalista. “Our God is still the same as the Christians, we still believe in the Bible, but we also believe that Rizal was a sugo or messiah, and that he reincarnated in Tatay Felimon [Reambonanza], who is also a sugo or messiah.”

“Nakasulat pud gani si Tatay Felimon ug libro nga Nunc mi Tangere or Touch Me Now, ag kang Rizal kay Noli me Tangere or Touch me Not man to,” Patangan said. (Father Felimon had even written a book titled Nunc mi Tangere or Touch Me Now, Rizal’s book was Noli me Tangere or Touch Me Not.)

The Rizalistas claim their organization has grown to millions of members throughout the Philippines, which enabled the late Reambonanza to establish strong connections with big political clans, like the Marcoses.

She said that, although “Tatay Felimon is Rizal’s reincarnation, he impersonated the life of Jacob – from which Israel got its name – by having four wives and 12 children.”

The handyman and the cook

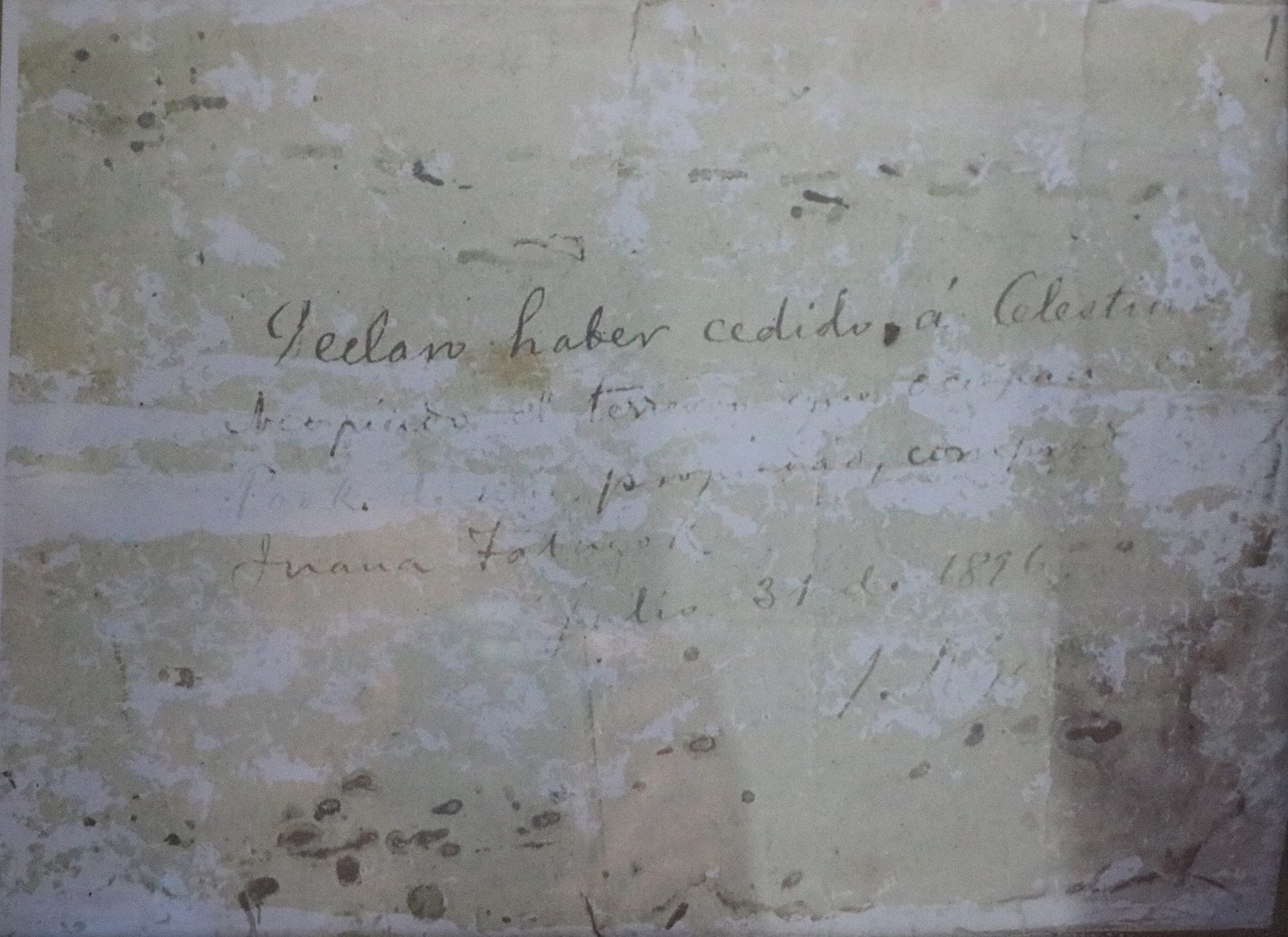

When it comes to the nine claims for titles inside JRMPL, there may be no problem when it comes to question of “prior rights” because Rizal ceded his property to their great-grandparents.

Anuncio Acopiado Jamarolin, 82, grandson of Celestino and Anecitas Acopiado, said his grandparents were given the property because they served Rizal during his exile in Dapitan.

“Si Celestino maoy tig-lampaso, guwardiya ug suloguon samtang si Anecita maoy tig-luto ug dunay panahon nga maoy tigpanguha sa kuto ni Trinidad, si Trinidad ra man kunoy kuto-on sa mga magsuong Rizal,” Jamarolin said. (Celestino scrabbed the floor of Rizal’s house, served as his bodyguard, and did errands, while Trinidad was the cook and at some time pulled lice from Trinidad’s hair. Trinidad was the only one with lice in the family.)

He recalled his mother Felisa Acopiado-Jamarolin – one of Celestino and Anecitas Acopiado’s nine children – to have told them that it was late afternoon on July 31, 1896, when Rizal was fetched by a small boat that would bring him to Steamer España anchored off Dapitan Bay.

Dapitanons turned en masse to see Rizal off while the town band played Chopin’s “Marche Funebre.” Then, suddenly, when Rizal was knee deep on shore, Anecitas came running and asked him how she could prove that he had given his property to her and her husband.

“My mother told us that Rizal got a paper and a pen and wrote that he ceded his property to Anecita and Celestino,” Jamarolin recalled, as he showed the framed copy of Rizal’s letter.

Jamarolin emphasized that they never had in mind to illicitly claim the land of Rizal: “Sigi gyud mi niyang ingnon nga respetuhi ug higugmaa ang kabilin ni Rizal kay dako kaayo na siyag natabang nato,” he stressed. (My mother always reminded us to respect and love what Rizal’s had given us because he helped us a lot.)

Conflicting surveys

The application for titles of Anecitas and Celestino’s nine descendants are almost done, but the problem is their claimed lots have included the foreshore area, buffer or salvage zone, and timberland that by law could not be titled.

The nine applications for titles passed the scrutiny of CENRO-Segabe and were sent to DENR Region IX in Pagadian City. The “survey plan” was eventually approved by the regional office in January 2019, and the final step would already be the issuance of titles.

However, Adelaida Borja of CENRO-Segabe issued a certification dated January 25, 2021, stating that actual ground verification found some parts of the nine claims are within areas considered as “easement” or “salvage” zone in accordance with DENR Administrative Order 2007-29 or the Revised Regulation on Land Surveys.

Borja’s certification added: “The survey plan submitted in support to their applications for Free Patent…indicated that Salvage Zones are outside their claimed applied lots, which run contrary to [CENRO-Segabe’s] recent findings, thereby recommending said issues and concerns to the Regional Executive Director for further in-depth investigation and resolution.”

Asked about this, Gadot – who just assumed the post of regional executive director in-charge on Septembert 15, 2021 – said the submitted “survey plan” was approved, though not during his tenure, “because everything were in order” and was sent back to CENRO-Segabe for the issuance of titles.

“But if CENRO Officer Borja would contest the approved survey plan – which they themselves prepared, processed, and endorsed to us for approval – all she would need to do is prepare a complete staff work with the recommendation to cancel the plan,” Gadot stressed.

Stretching the DENR surveys

The delay prompted Jamarolin to ask why the nine applications encountered problems when these claimed lots are located in the middle of two lots that were issued titles, about which an officer at DENR-9 said, “Naay ga-inat ana (Somebody has stretched the survey).”

“Inat-inat sa (Deliberately stretching the) survey – that happens in the DENR many times,” the official told Rappler. “There was even one claimant, a national government official assigned in Dapitan, whose lot she applied for titling was stretched by her surveyor and ate up two other adjacent lots. The case is still in court.”

The case of the nine claimants started in 2012, when engineer Domingo Chiong, then DENR-9 chief for isolated survey, conducted a survey for their claim. The survey was rejected because it covered Dapitan Bay.

However, geodetic engineer Jessica Ladera of CENRO-Segabe revealed to Rappler that the same survey was resurrected in October 2018, and that this time the signatory was geodetic engineer Maxel Ponce, who was a non-regular employee of CENRO-Segabe in 2012 and now appointed Engineer III of CENRO-Guipos in Zamboanga del Sur.

Ladera said Republic Act 8560 or an act regulating the practice of geodetic engineering in the Philippines, prohibits any geodetic engineer from affixing his or her signature on a survey conducted by another.

She also sent a letter to DENR-9 Regional Executive Director Crisanta Marlene Rodriguez on March 22, 2021, asking for an in-depth investigation because the survey plan was eventually approved in January 2019 despite “glaring irregularities.”

For one, she said, the survey plan was approved based on a certification by geodetic engineer Ronilo Saguin, the chief of the Survey and Control Section, that the “original lots fall within Alienable and Disposable Land,” even if Saguin had no authority to do so.

Ladera said that, based on their Manual of Authorities, the approving authority on Certification of Status of Land is the CENRO, in this case CENROfficer Borja.

She also said it was also irregular that attached with the survey plan was a certification from the PAMB of JRMPL without the name and signature of the PASu.

“Until now, no in-depth investigation was made. My letter was just taken like a piece of paper,” Ladera told Rappler.

Asked why no investigation had been done, Gadot said that it was up to CENROfficer Borja to recommend the cancellation of the approved survey plan if they found irregularities in the documents and the process.

The government is its own problem

Finally, the government’s own protection efforts of JRMPL have become more difficult and much less effective with ill-thought government infrastructure projects.

When former protected area supervisor Balbosa was on a boat passing by the Rizal Park on February 13, 2021, he noticed that a road was being built across the JRMPL.

After conducting a survey of the area the following day using a drone, Balbosa learned that it was the Provincial Engineering Office that was constructing a road in the middle of JRMPL.

About three days later, Balbosa sent a letter to Zamboanga del Norte Governor Roberto Uy, asking him to stop the road construction.

Eventually, the construction was stopped, and PAMB filed a complaint against the provincial government. It was recently dismissed by Dapitan City Prosecutor Lynbert Lo – “dismissed out of technicalities,” said Gadot.

Gadot said Balbosa had re-filed the complaint.

The provincial government did not directly respond to inquiries from the media on why a road was constructed in the middle of JRMPL, but it released a news item through the Provincial Information Office and posted it on their Facebook account, saying that the clamor of the people within and adjacent to JRMPL prompted them to construct the road.

Dapitan City Mayor Rosalina Jalosjos was not satisfied with the explanation. She said what the provincial government did was a “wanton desecration of a protected land, and not just any protected land.”

The mayor added that the provincial government’s refusal to coordinate with the city government, the PAMB, or even the officials of the two barangays where JRMPL is located was an insult not just to Dapitanons, but to the entire Filipino people.

Governor Uy, who is on his last term as governor, is running for mayor in Dapitan.

Mayor Jalosjos said the construction of that road has already felled centuries old trees and, if not stopped, “we also could no longer stop the encroachment of people inside JRMPL and the eventual destruction of JRMPL.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.