SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

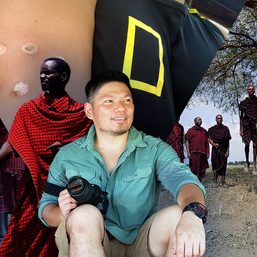

The Serengeti plains are so vast that hiding millions of large animals is a breeze. Bouncing inside an open-topped Land Rover, our all-Pinoy team glasses the grass for wildlife. Aside from the occasional startled bird, few show themselves.

In Swahili, the trade language of East Africa, safari means to go on an adventure. And after years of dreaming and planning, we’re finally on safari in Africa.

“Zebra, wildebeest, and other grazers follow the rain. They tend to avoid areas like this, where grass has grown tall enough to hide predators like lions and leopards,” explains safari guide Ray Shirima. Ringing us is a steadily-swaying grass sea five to six feet tall.

Islands of granite called kopje stand sentinel over the savannah, while stands of baobab or acacia break the horizon.

After an hour, our Rover rounds a bend. Suddenly, the animals are there. Hundreds of wildebeest and zebra graze serenely alongside dozens of gazelle and a handful of giant eland. “See the grass in this area? The animals have been feeding here for days,” points Ray.

Instead of fields of tall grass, the area resembles a giant golf course, with inch-high grass adorned with little green piles of grazer dung for kilometers on end. In Africa you’ll clearly see how various animals peacefully coexist. Zebra graze solely on the tallest grasses. Various antelope munch on mid-sized grasses, while wildebeest browse contentedly on the stubble.

I try to imagine just how many animals it takes to mow down a horizon’s worth grass. Only then do I understand the scale of life in the Serengeti, home to the largest mammal migration on Earth – a 2,000-kilometer long journey from Tanzania to Kenya and back.

The Great Migration begins with the birth of nearly half-a-million wildebeest calves in the southern Serengeti from January to March. When the grass dries up in May, the herd – up to two million animals strong – journeys north, bolstered by hundreds of thousands of zebra and antelope. As one, they leave Tanzania for Kenya’s Masai Mara Reserve, where the grass is quite literally, greener. The herds are so immense that they form an unbroken column, 30 to 40 kilometers long.

Perils galore await the herd en route to their grazing grounds – from hungry prides of lions and packs of hyenas, to the dreaded crossing of the Mara and Grumeti Rivers, which whittles down tens of thousands of the weakest, sickest, and unluckiest animals. Over 300,000 grazers die each year – but enough survive to continue the great trek back to Tanzania and the Serengeti plains each October, where the age-old cycle shall begin anew.

This, more than anything I’ve encountered over a lifetime watching wildlife, illustrates the fluid nature of life. As explained by Mufasa in The Lion King:

Everything you see exists together in a delicate balance. We need to understand this balance and respect all creatures, from the crawling ant to the leaping antelope. We eat the antelope, but when we die, our bodies become the grass, and the antelope eat the grass. So you see, we are all connected in the great Circle of Life.

Nature is a system where each beginning is also an end, where each death triggers some form of rebirth. This gives us hope, for it shows how death is never the end of the journey, but merely a continuation of life. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.