SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

In Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), the first thing we see is an aerial shot of a crowded and busy park.

Cacophony overwhelms the opening visuals. Street-side banter, random music, and other noise accompany the chaos of people going about their respective business. Coppola’s camera slowly zooms in and centers on one briefcase-carrying man, played by Gene Hackman, walking his way to work, oblivious of the fact that are eyes are on him. In just a few minutes, Coppola was able to evoke a feeling of paranoia, a sense of being perpetually watched and the dread of losing privacy even in the safety of a very public place.

Sign of the times

Steven Soderbergh’s Unsane has a similar scene.

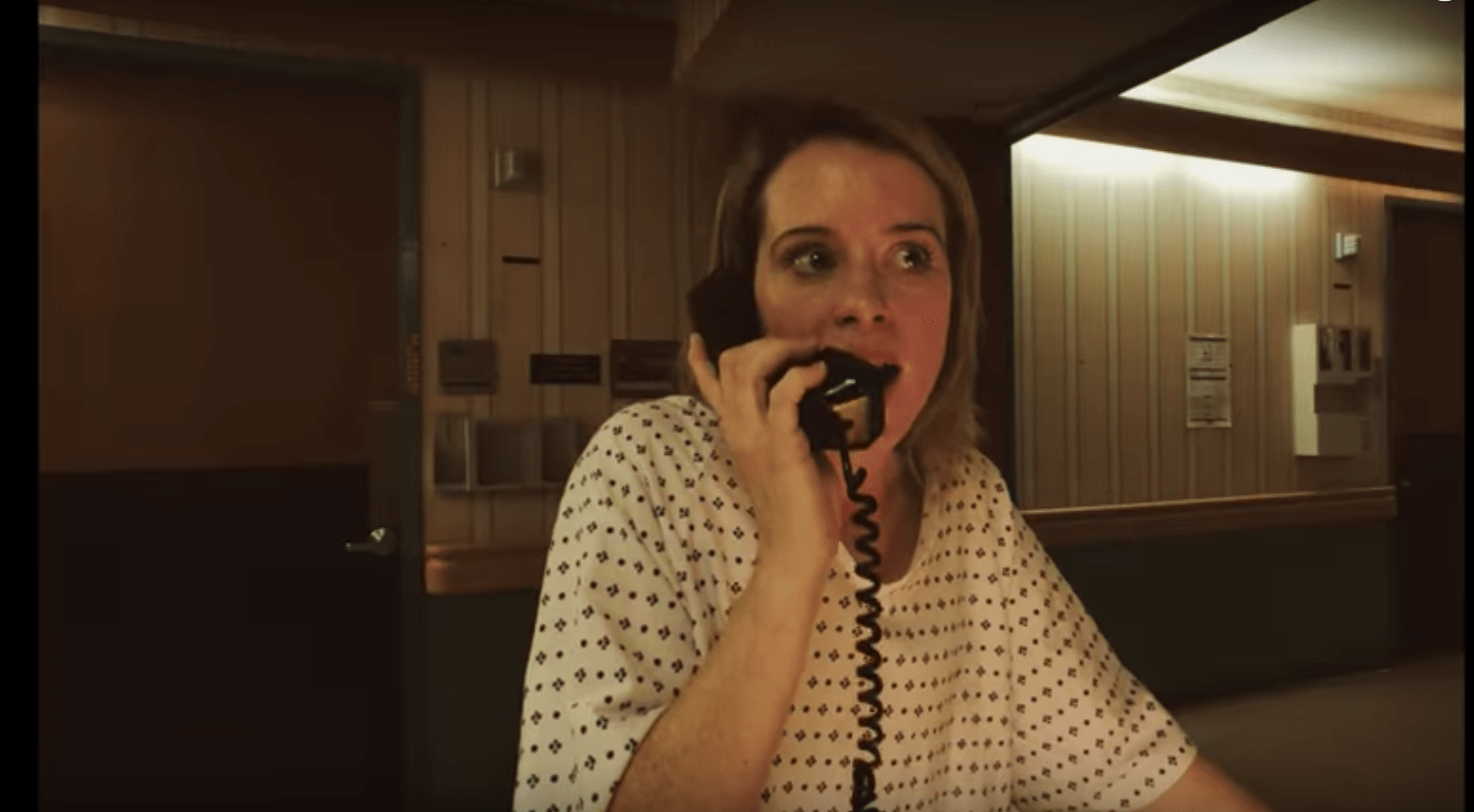

Right after its introduction wherein we hear a dreamy statement of adoration by a mysterious male over a nightmarish visual of a decrepit forest, the audience sees Sawyer Valentini (Claire Foy) walking to work. Soderbergh has his camera hidden behind bushes and other street structures. Like Hackman’s character in The Conversation, it seems that Sawyer is unaware that she is being watched.

We later find out that she probably knows, except that she can’t do anything about it. It’s just a sign of the times. Privacy is a thing of the past, at least in this particular portrayal of America by Soderbergh where the ills of corporate greed and the advances of technology have given rise to an epidemic of mental instability.

She starts to work, argues with a client, and gets praised by her boss before being the subject of a very awkward sexual advance. After work, she goes on a blind date that seems to have been going great – until she cracks just before getting steamy with that night’s random man.

She then goes to a clinic to talk to a shrink, where she confides her very many neuroses that living her kind of life gives her. Upon the recommendation of her shrink, she decides to have herself checked into a mental facility. This turns out to be the start of a loony bin-bound thriller that echoes the kind of wildly insane and sometimes raunchy shockers that never gets made in this age of unimaginative spectacle that rely too heavily on special effects than visual moods to provoke emotions.

Shot on an IPhone

Shot entirely on an IPhone 7, Unsane has the mood and feel of a film totally unhinged from the grime-filled but still glossy aesthetics of most Hollywood thrillers.

Soderbergh owns the micro-budget he chose to contend with.

He doesn’t attempt to turn the visuals the IPhone 7 is capable of into unnecessary gold. He sticks with it and in so doing creates a defined look, one that isn’t unlike the one we see from student films that have to make do with a very meager budget except that Soderbergh, who is also Unsane’s cinematographer, treats the aesthetic as essential to the tale he is telling.

His camera seems to be placed in nooks and crannies, creating angles that evoke an imagined surveillance, a sense that there is some sort of surreptitious intrusion to the characters’ personal spaces and private conversations. The film never feels detached from the looming and pervasive craze that it so fluently defines both within its main character and the world she is existing in.

David Wilder Savage’s score, which is reminiscent of the dingy beats of the B-movies of yesteryears, complements the film’s very specific aesthetic.

Tight, taut and fully realized

Unsane is perfect in terms of consistency.

It smartly opts not to overreach its ambitions and as a result remains a tight, taut and fully realized film whose crafting and themes are never at war with each other. – Rappler.com

Francis Joseph Cruz litigates for a living and writes about cinema for fun. The first Filipino movie he saw in the theaters was Carlo J. Caparas’ Tirad Pass. Since then, he’s been on a mission to find better memories with Philippine cinema.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.