SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – I tell Dr. Thomas Armstrong about my son who draws war scenes, blood and death and all. For an 8-year-old, he knows a lot about World War 2 tanks and makes models of them using LEGOs. He talks to his dad about strategic flanking. He asks us uncomfortable questions about Nazis.

Half-jokingly, I ask Dr. Armstrong if the bloody drawings should worry me. He smiles and says, “It’s wonderful he is fascinated by history!”

Fascination is a child’s natural, ideal state according to this psychologist and teacher. In his 35 years of teaching, he has taught primary school children and doctorate students, so I suppose I can completely laugh at my question now.

Armstrong is also an award-winning author on learning and human development. His 14 books have been translated in 26 languages, including The Best Schools: How Human Development Research Should Inform Educational Practice, Awakening Genius in the Classroom, The Power of Neurodiversity, and ADD/ADHD Alternatives in the Classroom.

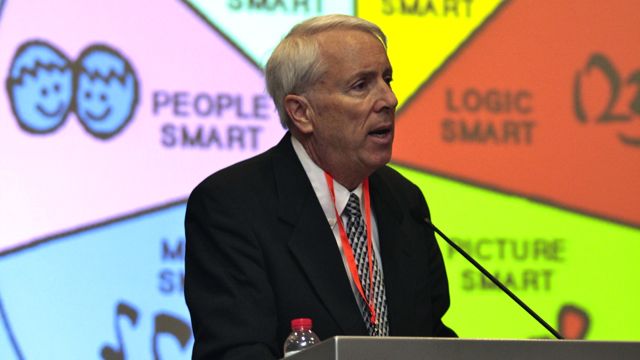

He recently visited Manila to be the keynote speaker at this year’s Super Kids 2012 Conference, where he talked about ideal learning environments and how children are “all kinds of smart” not just limited to reading, writing and math.

To research-savvy teachers, Dr. Armstrong is some sort of rock star. A few school directors came to the conference all the way from the province to hear the educator whose guidance has been sought by many — from the BBC and Sesame Street to the European Council of Schools, the Singapore government and other state departments of education.

I was able to chat with the author/educator about his advocacy for more Human Development Discourse in schools. He was candid about his frustration with children being stressed-out by tests and the use of textbooks.

Nikka Santos: How did your own childhood and education lead you to your work with children?

Dr. Thomas Armstrong: I always learned differently. I’m left-handed, an issue back then. As a child I think I was artistically inclined, but many of my art teachers were actually mean.

My father suffered from severe depression and this had a big impact on our family. It was very difficult.

I think because my childhood was traumatized I felt strongly that other children should not to be traumatized. I became very interested in how to support their development.

NS: You see certain aspects of traditional education as being harmful to child development. This is the heart of your advocacy for Human Development Discourse versus Academic Achievement Discourse.

TA: In learning we should be less concerned about test scores and more concerned about developing the whole human being.

Think about creative development, for example. What happens with creativity in an environment where everyone is overly concerned about test scores? You can’t be creative in a test.

NS: You think teaching-to-the-test is actually harmful?

TA: It is. Many wonderful things, valuable things that deserve to be taught… when they’re not in the test, they’re ignored or discarded. So they lose access to that knowledge.

NS: In The Best Schools, you say more than teaching-to-the-test children need to learn to love learning, to imagine, create, to think critically. You’d rather have them involved in projects. Less pop-quizzes, more experiences. But then there are those who ask, “Isn’t academic achievement a good thing?”

TA: Yes, it is. In fact, academic achievement is part of the development of the whole person.

It’s only when it becomes the main focus of learning that it becomes a problem. Academic achievement is important, but it must stem from a love of learning. We should not destroy this intrinsic love of learning that children are born with.

If we create this atmosphere where the test is the most important thing, then we starve their curiosity because they’re so busy studying for those very limited questions to a test. We then we miss the main point of education.

NS: For young children, you believe one of the best ways to learn and build life skills is through play.

TA: Let’s define play first. Play is not an organized soccer game. Play is not playing a video game. Real play is open-ended. It involves using the imagination. It’s creating. Building with blocks. Playing in sand. Exploring the outdoors. Navigating relationships in the playground.

NS: The playground — that’s as real-life as you can get. Another aspect of traditional education that’s not “real-life” to you are textbooks. You don’t like textbooks.

TA: If children are working on Reading for example, they need to be exposed to original materials, to great literature, to actual historical documents for history, to stories about scientific achievement. The best books are the books you find in the library.

NS: Books that make you think and feel. Books you can bond with, right?

TA: Yes! Who bonds with textbooks? Where’s the gripping story in a textbook?

NS: You visited a Philippine school. Your impressions? Did you get to interact with the students?

TA: I went to a preschool, Explorations and also Keys (Grade School). I certainly saw the Human Development Discourse in the classrooms.

I spoke to several students and they were very articulate about what they were doing and why they were doing it. I particularly remember the 7th and 8th graders who were engaged in their own projects. I was impressed with the diversity of projects. Some were working on musical compositions, some were reviewing portfolios of work they were creating over the course of a few months. Some were working on stories they had written.

It was a very rich environment. It was so wonderful to see these students making choices, monitoring their own progress and being engaged with the material and having a sense of confidence about themselves as learners.

NS: You believe schools should engage students in metacognition; this is important when they become very hormonal during their teen years.

TA: Metacognition means being able to think about how you think. This is very valuable especially for adolescents because their emotions are raging during puberty.

By the time children reach the ages of 11 or 12, certain spikes occur in the growth of areas of the brain, which may be correlated to their ability now to think in more abstract ways. No longer do they need to think in terms of concrete objects. That’s why Algebra is appropriate for 12-year-olds. They can now deal with a = b + c squared without worrying, what is “a” in the first place? They can now deal with pure concepts.

NS: So they’re in an emotional, impulsive stage, but as it happens they can also better understand concepts like self-awareness, social justice.

TA: Exactly. Now you can really engage them in social development, in personal development. Cognitively, they can really understand the process of decision-making. This can help them develop good study habits, better health habits.

NS: But schools and parents still need to guide them towards this…

TA: That’s why the stringent focus on academics ignores huge issues that could make the difference between a student that is healthy and positive versus becoming addicted, depressed and anxious.

The stakes are high. We have to develop the whole child, not just academic proficiency.

Emotional growth, even spiritual growth… these must come with intellectual growth. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.