SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Health workers are frontliners in the world’s battle against Ebola in West Africa. To date, the deadly virus has already killed more than 300 health workers, and the outbreak is far from over.

The United Nations (UN) this week said more foreign health workers and specialists are needed in areas where the disease is still spreading quickly. (READ: Ebola still ‘flaming’ in parts of Sierra Leone, Guinea – UN)

While the Philippines has pledged to give $1 million to the UN, it has decided not to send medical workers to the epicenter of the outbreak. But the government’s decision has not stopped Filipino doctors from helping.

On October 17 – a day after the government announced it will not be sending health workers to West Africa – Dr Natasha Reyes began her month-long medical mission as medical coordinator for the Ebola response of Doctors Without Borders’ (MSF) in Liberia.

“It’s a little party when [patients] get discharged, [when] children [and] families leave together,”

– Dr Natasha Reyes, medical coordinator, Doctors Without Borders’ Ebola response in Liberia

The Filipina doctor has been with the non-governmental organization since 2007 and has worked in several African outbreaks in the past, including cholera in Sierra Leone, and measles and hepatitis E in South Sudan.

More recently, she was MSF’s emergency coordinator for Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan).

Reyes knew how dangerous Ebola is, but she went to Liberia anyway, because people needed help, the country’s health system needed as many professionals as possible, and a lot of work needs to be done.

She also knew the best way to fight the outbreak was to get it at its source.

“I didn’t go there blindly…I thought about it carefully, spoke about [it to] my family to make sure they understood, [and] prepared myself [mentally and] emotionally,” Reyes told Rappler.

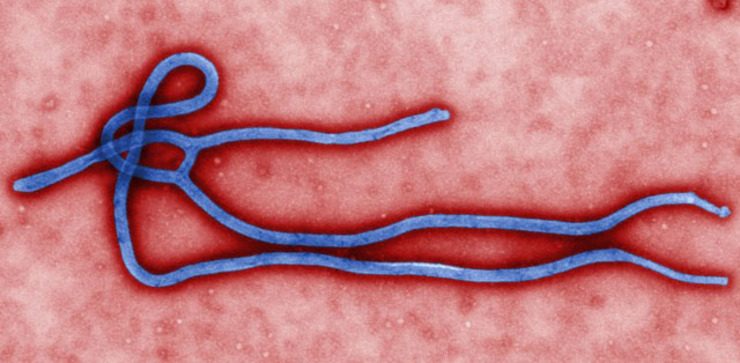

The Ebola virus, which can be transmitted through bodily fluids, causes severe fever, muscle pain, weakness, vomiting, and diarrhea. In some cases, it also causes organ failure, unstoppable bleeding, and can kill victims in just days.

As of December 10, the World Health Organization said the 2014 Ebola outbreak has already killed 6,583 out of 18,188 cases, mostly in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone.

On the ground

When she arrived in Liberia’s capital city Monrovia, Reyes saw how Ebola has changed the West African country in more ways than one.

“Africa is very vibrant, [with] kids playing in streets [and noisy] markets. [But] when I arrived in Monrovia in mid-October, it was very quiet. Not that many people [were] in the streets. Ebola has not just affected the health of Liberians, but it has really changed their way of life,” she said.

The economy of Monrovia is also affected, Reyes observed. Schools and businesses were closed down, and many lost their jobs either temporarily or permanently.

During Reyes’ stay, the MSF treatment center in Monrovia had over 100 patients, and at its worst, some patients had to be sent home for lack of bed space. Ebola’s survival rate is at 40%, but some survivors face discrimination in their communities.

The number of infections has decreased since then. David Nabarro, the UN coordinator on Ebola, earlier hailed the global and national responses to the outbreak, highlighting a sharp drop in transmission rates in Liberia.

Morale of health workers has also stayed up, Reyes said, and communities are beginning to change their behavior towards the disease.

“It’s a little party when they get discharged, [when] children [and] families leave together,” she recalled.

Ebola is still feared by many, but with more knowledge going around, many misconceptions have already been addressed. (READ: 5 misconceptions about Ebola)

Health workers are not letting their guards down either, as they work on improving health systems and protocols, including contact tracing, health promotion, and the referral system.

Mental health is also part of the intervention. MSF, for instance, has counseling teams who go inside high risk areas to talk to families and individuals traumatized by the disease.

She said doctors need to rely on science and what is known so far about Ebola to protect themselves. While it is true that Ebola is deadly, it is not easy to get infected unless there’s direct exposure to body fluids. (READ: Fast Facts: Ebola)

“There’s that vigilance all the time. The whole time I was absolutely aware of what I was doing whether outside or inside high risk area, when leaving, and removing [personal protective equipment]. If you just came from a high risk area, be careful [in removing] it – [you] have to be aware of what you’re doing at that moment,” she added.

‘Good opportunity’ to help fight Ebola

TIME Magazine recently named Ebola fighters as its Persons of the Year for 2014, honoring health workers from MSF and other groups who “fought side by side with local doctors and nurses, ambulance drivers and burial teams.”

“So that is the next challenge: What will we do with what we’ve learned? This was a test of the world’s ability to respond to potential pandemics, and it did not go well,” TIME managing editor Nancy Gibbs said.

As the outbreak continues, Reyes said health workers are still needed on the ground – professionals who are willing to go and be trained.

“Material or economic resources can help but the problem now is I’m seeing Ebola treatment centers built in Liberia with nobody to man them. Some organizations are committed to manning them, but not enough,” she said.

For her, it would be a good opportunity for the Philippines to send its health workers to help fight Ebola on the ground, so Filipinos can experience treating the disease, interact with other health workers, and bring home lessons to further improve the country’s preparedness.

“Regardless of how each country protects itself and [its] borders, until you stop [the] outbreak [from] where it’s happening, every country [is at risk].”

– Dr Natasha Reyes

Reyes said foreign medical teams go home after 4-6 weeks of fighting Ebola on the ground. Although a part of her wanted to stay longer, her medical mission ended on November 17.

At least 5 Filipinos – including Reyes – have helped in the Ebola response of MSF in West Africa since the beginning of the outbreak. Filipinos also top the organization’s field workers from the Southeast Asia region deployed to humanitarian emergencies.

The Philippines is not completely closed to the idea of sending health workers to West Africa. In fact, Health Spokesperson Lyndon Lee Suy said Filipino doctors are currently there for “other activities.”

“Baka sa assessment nila makita din. Baka puwedeng magpadala or what. We’ll wait for their assessment (Maybe in their assessment, we’ll see it. Maybe we can send health workers. We’ll wait for their assessment),” Lee Suy told Rappler. – with reports from Agence France-Presse/Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.