SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Who would have known that the year after I became grandmother to a second-generation American would see me posting thoughts full time for a Manila-based news site?

Who would have known that the year after I became grandmother to a second-generation American would see me posting thoughts full time for a Manila-based news site?

As summer of 2015 dawned I accepted the invitation of a colleague and former star correspondent to share my opinions and observations as a woman, expatriate, Filipina, American, mother, nerd, community organizer, volunteer, and all of the above.

I thought I was a foot in retirement, my home my office, no deadlines, my time my own? Not now.

First summer

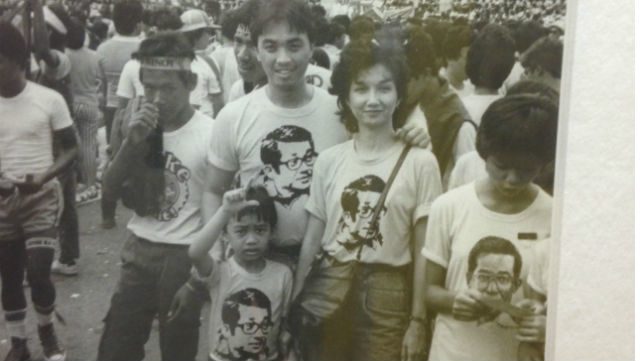

In the summer of 1961, Philippine News came to life in the hands of the indomitable Alex and Ludy Esclamado. In 1985, they offered a post to an editor on vacation from a Manila magazine critical of the dictatorship ruling the Philippines for 20 years at that point. They stoked me to unmask the regime that broke my father’s heart and probably ultimately killed him.

The Esclamados gave me a seat at the table of Filipino American empowerment. Succeeding publishers Ed Espiritu and his children cemented it.

My husband gave up his upwardly mobile marketing career and with our only child joined me in California to see why I was turning my back on the comfortable life we enjoyed in Manila.

All I ever truly wanted was to be like my parents – the journalists – watching, documenting, researching, reporting, analyzing, admiring or chastising, questioning authority, uncovering secrets that should not be; sparking thought, fueling conversation, triggering action – the better part of the profession.

Nobody gets rich being a journalist, unless of course they play ball with their subjects or moonlight as for-profit publicists, covertly or not.

“Periodistas,” as Dad and Mom identified themselves, didn’t punch clocks in their 24-7 vigilance for the scoop. A journalist no matter her or his beat knows everything that’s happening. Or should. Family often waits for them to catch quality time.

Subliminal

I grew up making those midnight phone calls to Dad, the managing editor, reminding him of his promise to bring home five and not two bars of Nestle’s Crunch, and have my expectations fulfilled each time. Never mind how he managed that while being stalked by the corrupt politician who had been subject of his daily relentless expose.

I’d cry begging Ma, the “society” editor, to stay and have miniature tea with me, Blondie, and Bella, the lifelike dolls she had brought home from a papal audience with colleagues she referred to even in their late 80s as “the girls,” but there was always this “luncheon” (who says that anymore?) she could not miss.

Instead we would play dress-up. I would stare as she lined her brows and painted her lips, slipped on her nylons, dabbed scent on her wrists and neck. I’d help her choose the purse and shoes to match her dress, and string the pearls around her neck for the finale. Then I’d do exactly the same on myself after she had left, stumbling in the stilettos while sashaying in front of her full-size mirror.

My parents may not have realized they were subliminal messaging by taking me to receptions, introducing me to names that jumped from the front page and faces that smiled from the newspapers, magazines and TV.

I shook hands with presidents foreign and our own (one was my baptismal godfather), feeling less thrill than if I had pressed the palm of John Lennon. The sea of humanity parted as I followed Pope Paul VI’s processional at Quezon Memorial. The phone rang with some whistleblower at the other end offering an explosive exclusive. A few hundred words changed lives.

Journalism was all-access pass, I soon realized, that came with much caveat:

Read ravenously. Stay curious. Build contacts, never ask for favors. Have no fear. Listen to your conscience. Be accurate, be fair. Pride over prosperity. Honor above all: I phrase my parents’ example.

Transformation

I realized all that after transforming from fashion editor to managing editor of the premier Filipino newspaper in the United States, the one that challenged the Marcos dictatorship by publishing reports banned as subversive in the Philippine government-controlled media.

I switched to news writing, earning snickers from Manila colleagues who still refuse to recognize me beyond the fledgling tapped by Eugenia “Eggie” Apostol straight out of graduation to find faces for the weekly covers and produce fashion pictorials for her magazine.

Apostol taught me to have fun at work, break free from convention, dare toward untrodden paths. Our Mr. & Ms. Magazine team annoyed the dictatorship by interspersing our “women’s” features with sagacious essays by Marcos critics, Eggie’s way of having her cake and eating it too.

When she launched Philippine Daily Inquirer, I was already across the Pacific, learning “advocacy journalism” from Alex Esclamado, whose newspaper flouted the cardinal rule of objectivity while touting “fearlessness.”

That was before cellphones and Google – when research was actual legwork and anonymity was anachronistic to the profession.

‘Advocacy journalism’

Esclamado was the most powerful Filipino American never elected. He did not need an official title to sit and sup with uncrowned heads of this country and call them on behalf of a friend in need.

We were two faces of the same coin, I told Alex the first time we met.

While he, the lawyer-turned-publisher, pulled no punches, I, the career journalist, laced my fists – so to speak. We shared the same compassion for the oppressed and contempt for tyranny.

When Consul General Romy Arguelles announced he was defecting from the Marcos regime and turned the tide against the dictatorship in Northern California, I was among few non-mainstream reporters standing over the heads of seated opposition leaders who took over the consulate in 1986.

When an Asiana Airlines jet crash landed in 2013, I texted Deputy Consul General Jaimon Ascalon, who replied immediately from a family gathering, and we got the scoop on the Filipinos on board, injured but alive.

When Philippine News turned 40, actress Sharon Stone stole the anniversary program by escorting her husband SF Chronicle executive editor Phil Bronstein, our keynote speaker.

Ten years later, we headlined Pulitzer laureate Jose Antonio Vargas, poster child of unknowingly undocumented immigrants, amplifying his fight for immigration reform.

Francis Espiritu had taken over as publisher by then and invited me back to headline key community issues, including domestic violence and elder abuse.

We began partnering with Rappler after one of our ace correspondents, California-born Ryan Macasero, decided to find his roots in his parents’ homeland, and took a job with the Philippines’ premier news website.

Old rules, new medium

One summer evening in Manila nearing the turn of the last century, a 10-year-old asked her father what life would be in the year 2000. What’s left to be invented when the telephone and the television were common in homes everywhere, the girl wondered.

As always, her father provoked imagination.

We have no idea what will come next but definitely it will change the world, said he who scorned the electric typewriter: Nothing but the Olivetti, whose steel keys echoed each dramatic flourish emanating from mind to fingertip to ribbon to paper.

The possibilities are endless, said the girl’s father.

I can imagine the copious commentaries that might have emerged from Dad’s rendezvous with a PC, had he survived lung cancer in 1989.

Mom, on the other hand, flirted with the laptop, on which she churned out a few of her own columns for a publication in Manila while on sojourn in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Women, indeed, tend to be more welcoming of change.

I cannot count the times I’ve left and returned to Philippine News, my life project. In 2002, I attended news writing classes at UC Berkeley to refresh myself, proving that the tenets of good journalism remain the same no matter the medium.

Now here I am, turning a new page, uh – post, as columnist for Rappler while consulting with Philippine News.

Dad was right about not knowing what comes next, and also about knowing that some things never change. – Rappler.com

Cherie M Querol Moreno is a keen observer of the evolving Filipino American community in the San Francisco Bay Area, subject of her 30 years of reporting for and editing Filipino-American publications. She founded and directs the family violence prevention nonprofit ALLICE Alliance for Community Empowerment and sits on the San Mateo County Commission on Aging. ‘Unbound’ is her long-running column which will now publish regularly on Rappler.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.