SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

In today’s modern economy, arguably no other technology has caused more tectonic shifts in the nature of production than the Internet.

One by one, the Internet is single-handedly killing such favored and beloved print media such as newspapers, magazines, and books. Encyclopedia Brittanica, for instance, has stopped publishing its famous 32-volume print edition in 2012, after 244 years. Why? In a word, Wikipedia.

Newspapers are also hit by the rise of Internet news. In the US, while total print ad revenues for all newspapers dropped by 55% from 2005 to 2013, online ad revenues rose by 66%. Indeed, printed news is becoming less and less profitable as evidenced by a recent selling spree of newspapers like the Boston Globe (sold for $70 million) and The Washington Post (sold for $250 million). Both these sell-offs occurred in just the past few weeks.

In the Philippines, the owners of The Philippine Star are planning to sell as much as 80% of the company’s stakes to PLDT’s Manny Pangilinan. In the words of Philippine Star president and CEO Miguel Belmonte, “Partnering with a tech company like PLDT will extend the life span of our paper. Our expertise is on publishing — as we know it, the hard copy. Since the digital age is upon us, we feel that their capability in that area is far superior than what we’re capable of doing. They will be a strategic partner to have.”

Digital revolution

Aside from the publishing industry, the Internet is also killing old means of private communication. Last July 14, 2013 the Indian government’s 160-year-old telegram service sent its final telegram.

Postal services around the globe are also feeling the pinch as email has become the norm, leading to closures and sell-offs left and right. In the US tens of thousands of post office workers have already been laid off, and counting.

Breakthroughs in computing and processing capabilities have also caused radical changes, so that even relatively new technologies—like landline telephones, optical disks (CDs, DVDs), digital media players, e-readers, point-and-shoot cameras, and video game consoles—are slowly dying already, what with the emergence of newer technologies like smartphones and tablets, which combine in one machine the functions of many previous stand-alone devices.

Aside from being far more handy, today’s smartphones and tablets can fare just as well (or even better) than most stand-alone devices. Smartphones and tablets also offer much more flexibility in functionality with the existence of apps and app stores which, through the Internet, harness the creativity and ingenuity of developers the world over. Whether we want to stargaze, tune our guitars, or plan our next road trips, there almost always seems to be an app for each.

Creative destruction

The incessant march of technological progress, driven by revolutions on the Internet and digital computing, goes to show that even relatively new technologies can be killed the moment newer, sleeker, and smarter ones emerge.

This phenomenon of technological displacement is hardly a new one: Back in 1942 the economist Joseph Schumpeter coined the term “creative destruction” to refer to the process of “industrial mutation” that “incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.” He even went on to say that creative destruction is, in fact, “the essential fact about capitalism.”

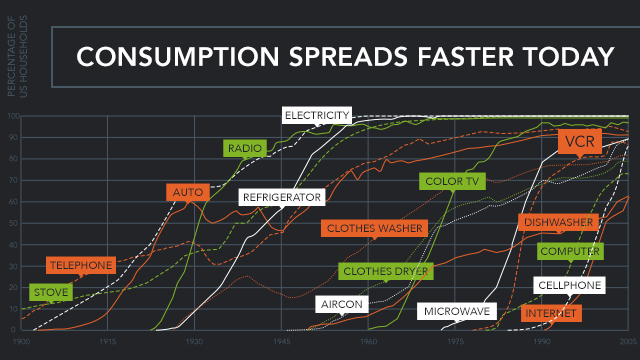

The figure below summarizes well the emergence of new technologies over the 20th century (though from a US perspective). Specifically, the figure shows the percentage of American households owning a variety of new products over decades, from refrigerators to microwaves, radios to colored TV, etc.

The incessant creation of breakthrough technologies, one after the other, often comes in the form of new consumer goods (like Henry Ford’s automobile), the development of new methods of production (such as the assembly line), and the expansion into new markets (such as Europe and Asia).

The viral spread of such technologies is the secret that keeps the capitalist engine running throughout decades and centuries.

Figure: Rate of technological adoption in US households. Source: Adapted from Visual Economics.

Painful change

And yet this technological march toward progress is hardly smooth-sailing or pain-free: creative destruction implies the (sometimes devastating) roiling and disruption of employment in various industries that are becoming relatively old, forgotten, or obsolete.

In particular, technological change can bring about considerable job losses, income reductions, and a higher degree of uncertainty for the future of those who will be displaced.

This seeming battle between man and machine has existed for a long time. In the 19th century, for example, the Luddite movement saw massive riots and protests held by English textile artisans whose jobs were threatened by a particularly innocuous yet very efficient invention: the automated loom. The Luddites wrecked these new machines in public, often resulting in clashes with the government and, in some cases, killings.

Today, though less violently, new technologies are replacing many jobs across several occupations. Advances in automation and computer technology are creating new job niches (like database administrators, systems analysts, and software engineers) just as fast as they are destroying many old ones (routine jobs held by secretaries, typists, bookkeepers, and cashiers).

Some are even suggesting that the job displacement effect of technology is one culprit for the slow rate of job creation in the US in recent decades.

Naturally, the knee-jerk reaction to the job-destroying aspect of technological change is to clamor “saving” such jobs from extinction, perhaps to prop up such industries with some help coming from government.

However, it’s not clear how much government can help to “save” jobs. For instance, it’s not as if jobs lost in the postal service or publishing industries will be regained by “undoing” the Internet. The Internet is, for all intents and purposes, here to stay.

Adaptation

Perhaps workers can be given aid as they search for new areas of employment. Or, in the event that retraining is required, the government can sponsor further skills development. Beyond that, however, any effort to resist the tide of technological progress will only prove to be an exercise in futility.

In today’s modern market economy, adaptation is the name of the game, and workers in these affected industries will simply have to innovate and recalibrate their skills set if they are to keep up with changing times.

Economists always say there’s no such thing as a free lunch. And in this fast-paced world we live in, adapting to both the creative and destructive aspects of technological change is the price we need to pay to bring about higher standards of living for all. – Rappler.com

Man holding a light image from Shutterstock

JC Punongbayan holds a master’s degree in economics from the UP School of Economics. He is also a summa cum laude graduate of the same school. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations.

This piece was inspired by Rappler and Google’s collaboration called #ThinkPH: The Internet, Big Data & You to be held on August 23, 2013 at the New World Hotel in Makati.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.