SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

There are many good reasons to abolish the pork barrel once and for all, as expounded by some writers in recent weeks here on Rappler.

For one thing, pork is often reduced to being a tool of the executive branch to muster support (and punish enemies) in Congress. This undermines the independence between the two branches of government, as was explained by Prof Carmela Abao.

Second, pork is also a way for lawmakers to increase their visibility in their hometowns by spending pork on various public works (like waiting sheds and basketball courts) bearing their names. Pork likewise perpetuates the cycle of patron-client relations between politicians and their constituents, as was explained by Prof Ron Mendoza.

In this piece I will try to highlight yet another good reason for the abolition of pork: There’s simply no relation between which districts get pork and which areas need pork the most.

In other words, the Priority Development Assistance Fund (or PDAF) has ceased to become relevant in providing funds to areas which need development assistance the most, thus rendering it an ineffective strategy for promoting regional development.

No vision

The lack of vision and thought behind PDAF as a development strategy is apparent from its very origin: the General Appropriations Act or GAA. Take for instance the 2010 GAA (pdf here). The section on PDAF starts off with a “menu” of projects on which the lawmaker can spend his or her PDAF allocation. This menu includes programs in education (e.g., scholarships), health (e.g., medical equipment), and public works (e.g., roads and bridges), to name a few.

One might expect, however, that instead of listing the shopping list at the outset, there first ought to be a proper overview as to what PDAF is all about, how PDAF defines “development,” and how PDAF relates to the government’s overarching strategy to promote growth and reduce poverty as expressed, for example, in the Medium-Term Development Plan.

In other words, prudence dictates that before spending a ton of people’s money on these projects, proponents of PDAF should show at least some iota of thought on the justification for such big-ticket items. Unfortunately, it seems no one can be bothered to explain on paper what exactly PDAF is for.

The lack of a rationale for PDAF has led to its reduction as a free-for-all where lawmakers get to spend taxpayers’ money hither and thither. The few safeguards we currently have against misuse and abuse of PDAF also seem to be largely incapable of stopping the channeling of such precious public funds to the likes of Janet Napoles (see the grisly details of the COA special report on pork here).

Pork and the poor

But just because some lawmakers’ pork is being misused doesn’t mean that all of pork is being misused — right? That is, districts and provinces that have higher poverty rates or higher measures of deprivation must somehow be getting a commensurately higher share of this development assistance funds, right?

Unfortunately, no: Back-of-the-envelope analysis of the data on pork funds received by district representatives between Fiscal Years 2010 to 2013 (first half) will reveal that there’s actually no relation between PDAF releases and development indicators like poverty incidence or the Human Development Index, as shown below.

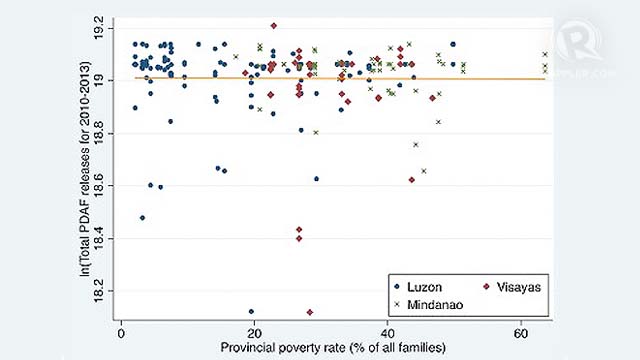

Figure 1 shows a scatterplot of total PDAF releases to all district representatives from FY 2010 to 2013 versus the poverty incidence of their home province in 2009. The orange regression line, which signifies the line of best fit between the points, suggests that there’s no relation between the amount of pork representatives claim and the poverty rate in their hometowns.

This is in contrast with the expectation that, since PDAF is intended to be a development measure, and therefore dependent on the needs of one’s district, poorer districts should require (and therefore claim) more PDAF than districts which are less poor. One should thus expect an upward-sloping regression line, not a flat one.

To some extent, some districts conform to the ideal upward-sloping trend. For instance, a district in Quezon City has a low poverty rate and claimed relatively little PDAF, while some districts in Zamboanga with high poverty rates claimed almost the full measure of PDAF.

Sadly, most other districts deviate from this ideal trend: relatively non-poor districts claimed as much PDAF as did very poor districts. When taken all together, a good part of PDAF therefore went to districts which are already relatively affluent and non-poor.

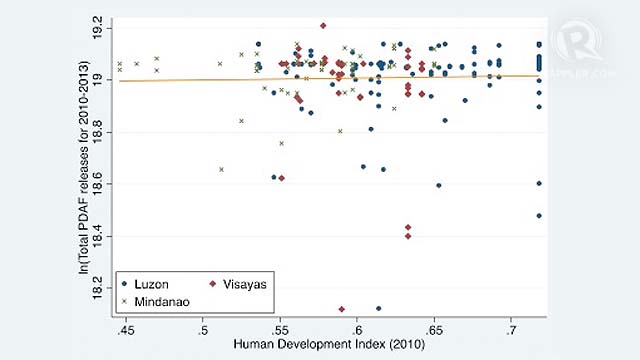

In Figure 2 we use an alternative measure of development called the Human Development Index (HDI) as reported in the 2012/2013 Human Development Report (see here).

The HDI combines in one measure 3 dimensions of development, namely life expectancy (as a measure of health), years of schooling (as a measure of education), and gross national income per capita (as a measure of standard of living). A higher value for HDI means a greater level of human development based on these 3 aspects.

Again, one would expect that, in districts located in provinces with a higher HDI measure, claims and releases of PDAF would be less than in areas with lower HDI. But instead of seeing a negative-sloping orange line, a flat relationship emerges — similar to when we used poverty incidence. This shows that there’s hardly any relation between how much PDAF is released to district representatives and where PDAF is needed the most in terms of human development.

Hardly an ‘equalizer’

All in all, this data on pork (which covers at least the past few years) reveals a virtually nonexistent relationship between PDAF releases and where PDAF is needed the most. In fact, it can be said that the two seem to be independent of one another! This suggests that the current system of distributing and spending PDAF is a terrible way of allocating resources intended for development projects.

One argument for the PDAF echoed by Sen Juan Ponce Enrile is that, it “equalizes” the allocation of funding across the regions.

Unfortunately, the data we’ve just presented shows that PDAF does anything but that: It actually allocates a disproportionate share of resources to affluent and relatively non-poor areas, so that very rich and very poor districts alike could receive the full measure of pork, regardless of how needy their respective jurisdictions are.

Put simply, a huge proportion of pork money is not reaching those in most need of it.

Alternatives

If targeting development money is the real agenda, then there are many good bottom-up alternatives to the largely top-down PDAF. For instance, the fiscal space currently occupied by PDAF funds can be redirected to social safety nets which target assistance to specific neighborhoods and households according to surveys of what people really need on the ground.

This obviates the need for lawmaker-representatives to second-guess the needs of the poor from atop the pedestals and lofty positions they operate in.

In other words, let’s all depart from the notion that our solons know what’s best for us, and should therefore be granted as much resources as possible to bring the poor out of poverty. In this day and age there are alternative and scientific methods better suited to the purpose of bringing development assistance to priority areas, while making sure that such assistance reaches the intended beneficiaries.

Beyond repair

It seems therefore that PDAF is a policy full of good intentions but riddled with unintended consequences. Retaining the pork barrel system this long seems to have led to more problems than solutions, more opportunities missed than seized, and perhaps more hardships for our people than if it was removed many years ago.

Our simple parsing of the data on pork hopes to contribute to the larger body of evidence suggesting that PDAF has become largely ineffective and irrelevant as a means of promoting development across the regions. It’s even entirely possible that PDAF has indeed worsened regional inequalities over the years, thanks to the culture of impunity and corruption it has brought with it.

Thus, perhaps it’s high time we put an end to Frankenstein’s monster that has arisen from our decades-old experimentation with pork. To my mind this can best be done not by trying to fix pork (which has been attempted time and again to no avail), but by finally abolishing it altogether. NOW.

JC Punongbayan holds a master’s degree in economics from the UP School of Economics. He is also a summa cum laude graduate of the same school. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.