SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Climate change disrupts community life and further weakens the already fragile social-economic fabric that still sustains the community.

Climate change disrupts community life and further weakens the already fragile social-economic fabric that still sustains the community.

As seen in the impact of Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan), this is especially true among rural communities suffering from scarcity even before disasters strike. Their sufferings are worsened by extreme weather conditions brought about by climate change. (READ: How climate change threatens food security)

The evacuation and permanent displacement of community members is one of the most disruptive effects of such disasters, but other effects are equally debilitating too.

Antique province was not Ground Zero for Yolanda and affected families in uplands didn’t have to be evacuated, but they had to contend with food insecurity.

With their traditional survival mechanisms threatened, the women felt the most impact.

‘Calendar of life’

Latazon, Tigunhao, and Guiamon are upland villages in the municipality of Lauan, province of Antique in Panay Island, western Visayas.

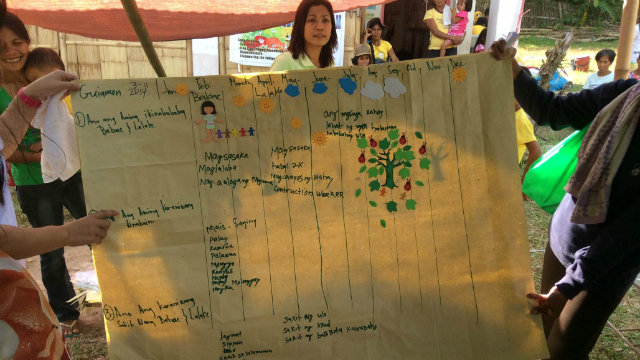

Through an activity called “Calendar of life” and a feeding project, the women of Lauan shared how they survived poverty and situations of lack – before Yolanda struck.

The activity was launched by Bulig Kababayen-an (Support Women) in March as part of its initial rehabilitation work.

Bulig is a network of mostly women cause-oriented groups formed in the aftermath of Yolanda. They respond to the needs of affected communities, especially of the women. Its members include the National Coalition of Rural Women (PKKK), Lilak, Sarilaya, Women’s Legal Bureau, and Focus on the Global South.

The women in these upland villages – reached only through a motorcycle ride or by trekking – used to source their food supply from what could be harvested from their small plots: peanuts, camote, root crops, corn, malunggay, kadyos and jackfruit. (READ: PH farm-to-market roads) Some also planted rice.

The food situation was not always one characterized by abundance as they could not buy other food supplies from the market with not enough cash to go by. (READ: Who’s afraid of food security?)

But they had relied on their traditional crops to help them cope. (READ: Why PH agriculture is important?)

In the months that followed Yolanda, a time period which the women marked in their “calendar of life” as November 2013 to March 2014, they became dependent on relief goods consisting of noodles, dried fish, canned sardines and rice.

At one point, even the local government had to say no to the abundant supply of noodles and canned food coming in, as they were feared to affect the villagers health situation.

Latazon village was luckier to be provided with fish supply from the river; meanwhile, Tigunhao village, with a drying river, was not as fortunate. (READ: Women, the sea, and food security)

Women hunger warriors

The Calendar of life also indicated a regularity in planting and harvest seasons that had assured food seccurity for communities.

This farming cycle was not just an economic activity, but it also sustained village life, familial and social kinship. All these were disrupted by Yolanda.

A number of women had to find work in the lowlands – like washing clothes – to earn much needed cash, as there were no harvests to provide for their families. (READ: Why most of the hungry are women)

The men left the villages as early as November 2013 to work as sacadas (transient farm workers) in other provinces.

As of March 2014, when Bulig returned, a number of houses had not been repaired though construction materials had been made available since January. This is because the sacadas had yet to come home.

In Roxas province and Panay Island, women from indigenous people’s communities devastated by Yolanda were forced to go down to lowland towns to work as housekeepers, according to a report from international humanitarian organizations.

Land of no women

But women’s capacity for self-reliance amid poverty, though enfeebled, cannot be totally broken.

Without the women leaders of the village-level self-help groups in Latazon, Tigunhao and Guiamon, the relief and initial rehabilitation efforts of Bulig would not have been conducted as efficiently.

Women have been at the forefront of fighting hunger, poverty, and hopelessness.

They drew up the list of beneficiaries, helped in assessing the situations of community members, organized the conduct of relief distribution, repacked goods, and negotiated with other community members who had not been affected by Yolanda so the latter would understand why they couldn’t be beneficiaries, especially of housing materials.

Owing to these efforts, there was no untoward incident in the conduct of the relief work. In Valderrama, the people had cleared the unpaved road of rocks a day before Bulig went there in January.

It made the trip less challenging for the motorcycle drivers and less threatening for Bulig members. (READ: The future of rural roads)

A woman’s touch

During the feeding project in March, the women of the Lauan towns brought their peanuts and root crops as their contribution to the meal.

It was the reliable hands of these women that chopped, washed, cooked the hearty, nutritious meals. (WATCH: PH Community kitchens)

Discussions on sustainable healthy diet led by Sarilaya complemented the feeding. As part of traditional hospitality, the womenfolk didn’t allow the visitors to leave without the padala consisting of whatever could be had from their plots.

Minds were also fed, through a session on women’s rights Lilak conducted.

The women’s hard work and community spirit could not dissuade members of these villages from performing their traditional dances and songs to celebrate women’s month.

These women are a big part of restoring the beauty of community life. – Rappler.com

Clarissa Militante works at Focus on the Global South; she is also the author of the novel “Different Countries,” which was long-listed in the 2009 Man Asia Literary Prize and published by Anvil Publishing in 2010.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.