SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

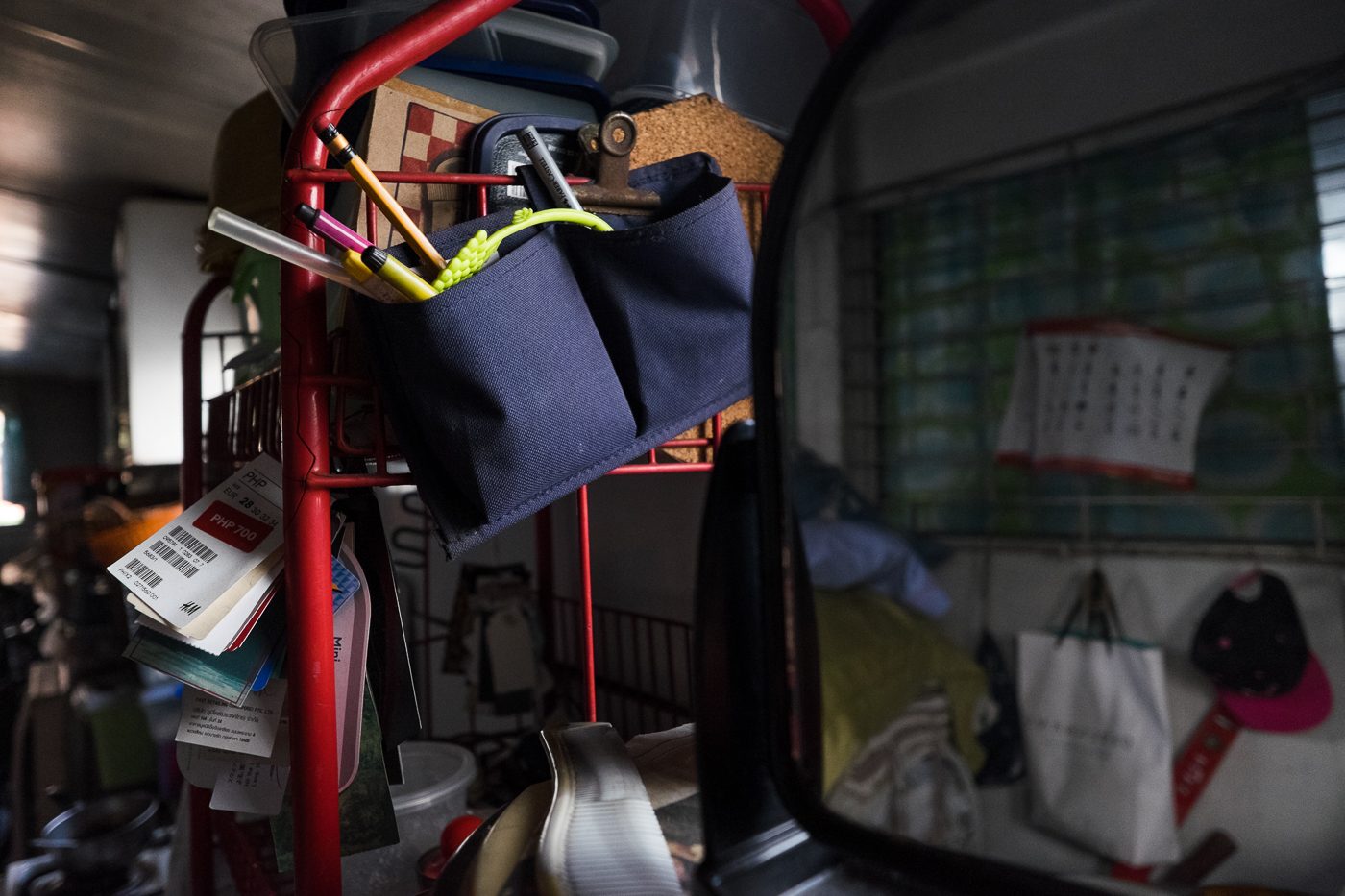

MANILA, Philippines – Anna tiptoes around the house and moves from one room to another with a laundry basket full of clothes. She mops the floors, dusts the shelves, refills the water bottles, and makes sure everything is clean and where it is supposed to be. She repeats this cycle in 3 different houses over a span of 6 days, and knows the corners of each room as if they were her own.

Her palms smell of soap most of the time and the veins on her hands are accentuated – marks of hours spent washing dishes and ironing clothes. When she gets home, she cooks for her 6 children and moves with the same care as she does in other people’s houses. She is 56 and this has been her life for more than 20 years.

Domestic workers’ rights

But she has never heard of Batas Kasambahay (Republic Act 10361), a law that took effect on June 4, 2013, which protects the rights of a kasambahay (domestic worker). The law mandates employers to pay kasambahays employed in the National Capital Region a minimum wage of at least P2,500 ($55) with 13th month pay in cash only, provide them with SSS, Pag-IBIG, and PhilHealth benefits, and allow them a daily rest period of 8 hours, and one day off weekly.

The minimum wage is at least P2,000 ($44) for those working in cities and 1st class municipalities, and P1,500 ($33) for those working in other municipalities.

Although Anna does not know how much she earns per month because she claims that her bosses deposit her monthly salary in her bank account for her, she says it is enough. All the benefits are given to her and even more. One of her employers even sends Anna’s youngest child to college.

But not all kasamabahays receive the same treatment from their employers. According to Maia Montenegro, exploitation is still rampant.

Compensation issues and working conditions

When Montenegro was 12, she started working as a kasambahay without her knowledge. The small amount of money she earned went straight to her mother, who did not tell her that she was being employed for cheap labor. She is now 33 and a member of the United Domestic Workers of the Philippines. She claims that even with the protection of Batas Kasambahay, a lot of domestic workers are still underpaid and overworked.

Lila (not her real name), a kasambahay in Barangay Socorro, Murphy, Cubao, earns less than P2,500 a month not only for household work but also for medical assistance. In addition to household chores, she also works as her employer’s nurse.

Other domestic workers are not enrolled with the SSS, PhilHealth, and PAG-Ibig, and if they are, they shoulder their own contributions.

Likewise, Ellen, an all-around maid who works for a family of 4 earns P170 ($3.70) per day. She works from 4 am to 10 pm and does not receive any social protection benefits and 13th month pay.

Implementation of Batas Kasambahay

Despite this existing culture of exploitation, Charisma Satumba, director of the Bureau of Workers with Special Concerns of the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE), claims that since the implementation of Batas Kasambahay, a lot of domestic workers have benefitted from the law. There are kasambahay desk officers in every DOLE regional office where employees can voice their concerns.

According to Satumba, the reports on abuse and unjust working conditions of domestic works have increased since the law was passed. She cited two disputes settled by DOLE: Archie Mendoza, who was illegally dismissed, was paid P40,000 ($875), while another domestic worker, who hasn’t been paid in 4 years, got P324,000 ($7,000).

But there are still those who remain in the dark. Satumba said it is difficult to monitor the working conditions of every domestic helper, especially since they are usually stuck at home and have no other avenues to voice their concerns unless they approach DOLE.

Malou Monge, who was a domestic worker for 7 years, adds that a lot of cases remain unreported also because domestic workers are not aware of what they are entitled to.

#OurHands Campaign

To increase awareness about domestic workers’ rights and to improve the implementation of Batas Kasambahay, Migrant Forum in Asia (MFA), together with the Philippine Decent Work for Domestic Workers Technical Working Group (DomWork TWG), launched the #OurHands Campaign on World Day for Decent Work.

#OurHands Campaign uses Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram to form a community of domestic workers both in the Philippines and abroad.

It aims to form a support group of domestic helpers where information about their rights and benefits can be disseminated, and their concerns can be heard by different organizations, government agencies, and fellow domestic helpers as well.

Julius Cainglet, assistant vice president of the Federation of Free Workers (FFW), a member of the DomWork TWG, said, “As the prime user of social media, especially of Facebook across the globe, a campaign like #OurHands will surely create greater solidarity among Filipino domestic workers both here and abroad.”

However, even though they are vocal about their rights, some employers still do not fully comply with the Batas Kasambahay. Tired of reminding their employers of their rights and benefits, some resorted to wearing statement shirts bearing their rights, hoping that the constant reminder will compel their employers to treat them justly.

Even though some employers remain abusive despite knowledge of the law, Monge believes that being vocal about one’s rights is still better than staying silent.

“Pag alam ng employers mo na marunong ka magsalita at alam mo ang karapatan mo, mas protektado ka (If your employers know that you are willing to speak up about your rights, you have more protection),” said Monge. – Rappler.com

$1 = P45.68

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.