SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – “I share a cell that measures 3 by 4 meters with 12 political prisoners. We have no access to sun or fresh air for days or weeks at a time. I am a photojournalist, not a criminal. Not even animals would survive in these conditions.”

Egyptian photojournalist Mahmoud Abou Zeid sent this letter from the cell where he has been holed up for 600 days. He is part of a long list of journalists who made the news for simply delivering the news. From detained journalists in Cairo, beheaded reporters in the Middle East, to murdered cartoonists in Paris, it’s been a shocking year of shooting the messenger.

Journalists marked World Press Freedom Day (#WPFD) on May 3 at a time press freedom is at its lowest point in a over a decade. Yet in an age of complex threats when everyone is a journalist, press freedom is no longer just for the gatekeepers of news.

“Most of journalism is done by the news media, but much of it is contributed by individuals using social media. Intimidation and attacks may start with journalism but they also threaten all other communications. So we’re talking of a continuum of freedom for a range of expressions,” said Guy Berger, UNESCO Director for Freedom of Expression and Media Development.

Beyond guns and shackles, this year’s global discussions on press freedom include Internet freedom, gender and labor rights. The issue concerns not just journalists meeting in Latvia for #WPFD, but also Filipino GMA7 regional correspondents protesting their sudden layoffs, and even the average netizen broadcasting on Periscope.

Where does press freedom stand today? Here are 5 key themes.

1. Terrorism in and out of war zones

Being a reporter is now one of the world’s most dangerous professions. As UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador for Freedom of Expression and CNN anchor Christiane Amanpour points out, holding up a mirror to society can lead to kidnapping, imprisonment or death.

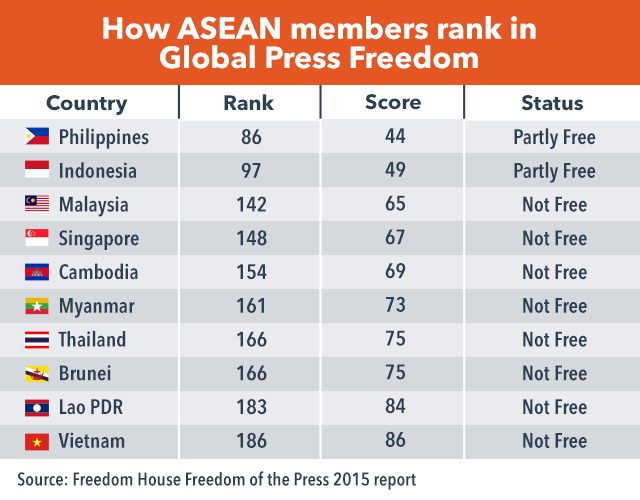

Annual press freedom reports of media watchdogs and human rights groups make for depressing reading. The Washington-based Freedom House said that only one in 7 people live in countries with a free press. The factors? The passage and use of restrictive laws, and journalists’ lack of access to protest sites and conflict areas.

Terrorism menaces conflict reporting and religious satire. The most glaring examples are the beheadings of journalists James Foley, Steven Sotloff and Kenji Goto in the hands of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), and the January attack on Charlie Hebdo that killed 12.

“Je Suis Charlie” remains contentious, with some writers boycotting the Pen International freedom of expression award for Charlie Hebdo, branding it “Islamophobia.”

Media and rights groups supporting Charlie wrote: “The right to freedom of expression also protects speech that some may find shocking, offensive or disturbing. Importantly, the right to freedom of expression means that those who feel offended also have the right to challenge others through free debate and open discussion, or through peaceful protest.”

Even in advanced democracies like the US, journalists struggle with harassment in covering protests like Ferguson, and the prosecution of leaked classified information.

Ironically, US President Barack Obama marked #WPFD by saying, “Journalists give all of us, as citizens, the chance to know the truth about our countries, ourselves, our governments. It gives voice to the voiceless, exposes injustice, and holds leaders like me accountable.”

2. ASEAN: Integrated repression?

As the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) gears up for integration this year, its members are also aligned in continuing the use of repressive media laws, and violence.

The Southeast Asian Press Alliance (SEAPA) brands Thailand the story of the year, with Bangkok’s press transforming from being relatively free to one of the region’s most restricted after the May 2014 coup. On top of draconian lese majeste laws, Thai journalists face the pressure of toeing the line of the iron-fisted junta.

Thai Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha infamously said he would “probably just execute” journalists who did “not report the truth.”

Myanmar also reverses its trend of media reforms after a series of journalist arrests, and the death of a freelance reporter in army custody. The New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) lists it as the 9th “Most Censored Country,” along with fellow ASEAN member Vietnam at 6th place.

Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak also backtracks, reneging on his promise to repeal the archaic Sedition Act of 1948. Najib’s government uses sedition to target the political opposition, the press, and activists, and even strengthened the colonial-era law. Defamation remains a criminal offense in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines.

The Philippines remains the region’s poster child for impunity, ranking third in the CPJ’s index after Iraq and Somalia. The trial of the 2009 Maguindanao massacre, the single deadliest attack on journalists, drags on while the masterminds of the 2011 killing of broadcaster Gerry Ortega evade arrest.

President Benigno Aquino III is also not good at keeping promises to the media. After 5 years, his campaign commitment to pass the Freedom of Information (FOI) law remains unfulfilled.

3. Digital safety and women’s voice

Southeast Asia is a battleground for free expression online. With traditional media tied to politicos and tycoons, social media-savvy youth turn to the Internet as the alternative space for speech. The fight for control is on.

On Press Freedom Day, Singapore shut down The Real Singapore for undermining “public interest,” the first time the city-state closed a news website under its 2013 licensing regulations. In Vietnam, pro-government cyber trolls simply use Facebook’s “report abuse” feature to bring down dissident accounts and pages.

The cyber troops’ line goes: “We just need to say ‘abusive contents’ for inciting ethnicities, and it is done.”

After the Snowden revelations, safety nowadays entails protection not just from physical assaults but from snooping as well. Journalists call on government to ensure that surveillance is put under clear legal and judicial control.

Media practitioners and activists use encryption, and anonymity toolkits to improve privacy and security. The Tor Project, for example, is a software that allows netizens to hide their location and browsing history, and to secure connections to websites protecting passwords.

The UN is also pushing for a greater role for women in media online and offline, noting that they hold only 26% of top positions globally. Gender equality is not a problem in Philippine media but the world body believes women should also be represented in the coverage of issues, not just in decision-making.

4. Perils for freelancers and contractual staff

While Western journalists and correspondents of big media outlets often hit the headlines, it is freelancers and local reporters in the front lines of war who are most vulnerable to abuse.

The death of Foley and Sotloff put the spotlight on the limited funding, training, and support that freelancers and locals get. In response, more than 60 news organizations and advocates committed to provide them insurance, protective gear, first aid, and hostile environment training.

‘There can be no press freedom if journalists exist in conditions of poverty, corruption and fear.’

– Rowena Paraan, National Union of Journalists of the Philippines

In the Philippines, journalists’ unions decry a similar form of exploitation: the so-called “talent system,” contractualization and retrenchments. They created a hashtag for the cause: #BuhayMedia (media life), and a Facebook page with memes to boot.

Media workers blasted as callous the recent layoffs of hundreds of staff of GMA7’s regional stations. Broadcast giants GMA7 and ABS-CBN face labor cases from long-serving employees it terminated. Community journalists have a harder time making a living, with some employers not paying reporters at all.

Journalist Rowena Paraan said the arrangement is called diskarte (style). “This may entail knocking on the door of officials, letting them hear the recording of the commentary or news report that aired recently wherein the official is given much prominence. With fingers crossed, the reporter hopes that the official is grateful or happy enough to slip him or her a Ninoy Aquino bill.”

Paraan added: “There can be no press freedom if journalists exist in conditions of poverty, corruption and fear.”

5. Media associations, netizens push back

Despite the grim picture, speaking truth to power is an ever developing story. From Thailand’s media associations, Indonesia’s press council, Malaysia’s student activists to Vietnam’s group of independent journalists, both journalists and their public push back and speak up.

At the RightsCon convention in Manila in March, Southeast Asia’s netizens and civil society groups agreed to form a regional network of Internet freedom advocates to exchange best practices, set up a support system, and to lobby for an open and free web.

Independent journalists also tap cyberspace through initiatives like crowdfunding to sustain investigative reporting in remote locations in China and Sudan.

In the real or the virtual world, anyone who supports the free exchange of information is a press freedom advocate. Journalists are not criminals and animals that must be caged. Setting them free means telling the stories about the legal, social, and financial conditions that chain and imprison all truth-tellers. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.