SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Speak against human rights abuses and expect to be attacked by an online mob. Now imagine how intense the attack could be if you actually work for human rights organizations.

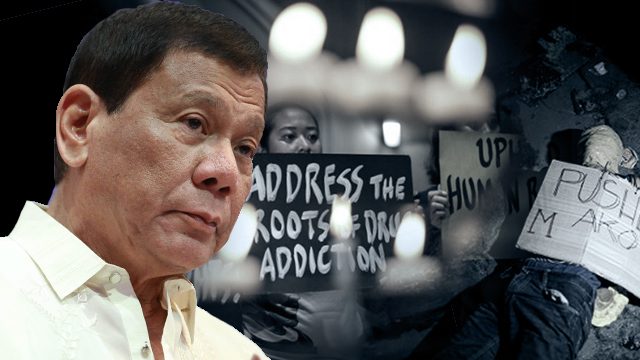

In the past year, advocates have been at the receiving end of harassment – rape and death threats, among others – ever since President Rodrigo Duterte unleashed his tirades against those critical of his war on drugs.

The Davao City mayor has been nothing but consistent in his hardline stance against human rights even before being elected. Threats to kill or behead advocates were a fixture in his various speeches.

Ellecer Carlos of In Defense of Human Rights and Dignity Movement (iDEFEND) said that with every curse and threat, Duterte effectively “demonized” human rights.

In his first year of office, the 16th Philippine president painted defenders as an obstacle to his promised “change.”

“Basically [Duterte’s threats] send a strong message to the public that these human rights groups are against development, against the change we want to happen,” Carlos explained. “These actually demonize human rights defenders.”

This is also the case with the Commission on Human Rights (CHR). A quick look at the comments section of stories that feature the Commission shows several attacks that depict them as criminal coddlers.

But the country’s leading national human rights institution – one of the best in Asia – is no stranger to criticism.

Commissioner Karen Gomez-Dumpit, however, admitted that they “have never been ridiculed or cursed as much as now.”

‘Extraordinary’ Duterte

How did it come to this? More than 30 years since Filipinos toppled a dictatorship known for its abuses, there are now people who associate human rights with opposing national development.

There has been a “muddling” of issues, disinforming people on purpose about the very mandate of the Commission and the concept of human rights, a challenge that advocates are grappling with. (READ: Hate human rights? They protect the freedoms you enjoy)

“Now more than ever, defenders have been demonized,” Gomez-Dumpit explained. “But more than that, the very concept of human rights has been attacked.”

Among the rights that advocates call on the government to uphold is the right to life – the “most challenged” human right today. (READ: In the PH drug war, it’s likely EJK when…)

“Perhaps the most challenged human right today is probably the right to life especially because of the rate of extrajudicial killings that [has been] happening,” Gomez-Dumpit explained, connecting it also to the death penalty.

Carlos, however, sees the dominant sentiment, particularly the victory of Duterte, as a “rejection” of past administrations. But Duterte’s case is extraordinary.

While previous presidents constantly denied that they had a hand in human rights violations during their terms, the strongman from Davao “actually boasts” about the killings and even encourages the public to kill drug users.

Duterte effectively labeled people who actually need medical intervention as “society’s undesired.” (READ: Shoot to kill? Duterte’s statements on killing drug users)

“What makes it even more extraordinary is that he put in place this permission structure whereby structured impunity has become entrenched,” Carlos said. “Even vigilante groups were encouraged to engage in killing the most vulnerable, the most impoverished people in Philippine society.”

Yet with the change he promised during the campaign period, iDEFEND observed that the new administration has failed to address issues outside illegal drugs and crimes.

Instead of focusing on programs that cater to the root causes, Duterte responded with violence.

This “solution,” particularly evident in his intense anti-illegal drugs campaign, has so far resulted in the deaths of at least 2,717 suspected drug personalities in legitimate police operations while 3,603 incidents still remain under investigation. By late June, the numbers had risen.

Most of the victims come from impoverished sector, making people refer to his war on drugs as a war on the poor.

“So now you have the war on drugs and war on terrorism which President Duterte and his administration is forcefully connecting,” Carlos said. “Ang response niya karahasan (His response with violence), instead of responding to the root cause which is bringing about the requirements of a life of dignity, economic, social, and cultural rights.”

The apparent lack of focus on poverty alleviation is obvious as the poorest sector was the least optimistic that their lives would be better in the next 12 months. The number of families who rated themselves as “poor”, meanwhile, rose to 11.5 million in the first quarter of 2017 from 10 million in December 2016.

Pressing on

Carlos pointed out that advocates were treated in the first year of the Duterte administration as no different from drug users – a “section of society worthy of elimination.”

“It’s a hate, inciting to hate, campaign against human rights defenders,” he emphasized. “Our safety in this context is compromised heavily because Duterte considers us as obstacles to whatever he wants to happen.”

Human rights has been reduced to a concept that a “destabilizer” would support. And if some netizens are to be believed, these rights are only for criminals. Memes posted on apparent pro-administration Facebook pages even ask the question: “Why is CHR siding with drug addicts who commit crime?”

According to Gomez-Dumpit, this belief is the opposite of what human rights are really about: universal rights.

“Nobody would want crimes to happen, we all want law, peace, and order,” she said. “But to say that human rights are only for criminals or that the Commission and human rights defenders are coddlers of criminals is actually not true.”

Despite the existing situation, CHR and various human rights organizations still continue with their jobs because the people, especially the voiceless on the ground, depend on them.

“We have to press on because the Commission is not immune to criticism in the same manner that the government is definitely not immune to any criticism,” Gomez-Dumpit said. “We just have to move forward and do our respective roles.”

Overcoming threats to human rights and defenders, Carlos admitted, is going to be a long struggle ahead.

“Mahirap pero dapat natin gawin (It’s hard but we need to do it),” he said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.