SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – In the era of fake news and authoritarian governments clamping down on dissent, the fourth estate is facing serious threats around the world.

Both human rights organization Freedom House and press watchdog Reporters Without Borders have dire assessments of press freedom: just 13% of the world’s population enjoy a free press, and the situation is nearing a “tipping point.”

Countries in Southeast Asia scored badly in the 2017 World Press Freedom Index, with the 10 nations making up the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) all falling in the bottom half of the 180-country list.

Among the ASEAN countries, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Myanmar were already the best-performing. Yet situations are still far from ideal.

Meanwhile, Brunei, Laos, and Vietnam ranked the lowest among the ASEAN countries.

Censorship by state authorities, harassment and intimidation by armed forces, and repressive press laws continue to stifle free expression. Here’s a look at the press freedom situation in each of the 10 ASEAN member-states.

Brunei

Journalists working in state-owned and independent media in Brunei practice self-censorship when reporting on religion or politics, as the country’s laws punish blasphemy or criticism of the Sultanate.

Under the Brunei Defamation Act, journalists can be punished for reporting “false and malicious” news. Bloggers may also be punished, as the law considers the “broadcasting of words by means of telecommunication” a publication in a permanent form, even if the defamatory statements are removed online.

Brunei’s Sedition Act also worsened press freedom as it became an offense to challenge the authority of the royal family. It also expanded punishable offenses to include criticism of the sultan and challenging the “standing or prominence of the national philosophy, the Malay Islamic Monarchy.”

Newspaper publishers, editors, or proprietors who publish items with seditious intent may face fines of up to 5,000 Brunei dollars and jail terms of up to 3 years. The government may also suspend publication for up to one year and prohibit violators from writing for other publications.

Although foreign newspapers are available in Brunei, the government must first approve distribution.

Cambodia

Media outfits in Cambodia are either owned by people close to strongman Prime Minister Hun Sen or are shying away from criticizing his government. In 2016, the government became more hostile towards independent media, particularly after the murder of Kem Ley, a prominent political activist and vocal critic of the government.

Journalists face the threat of being slapped with defamation suits, a criminal offense punishable by large fines.

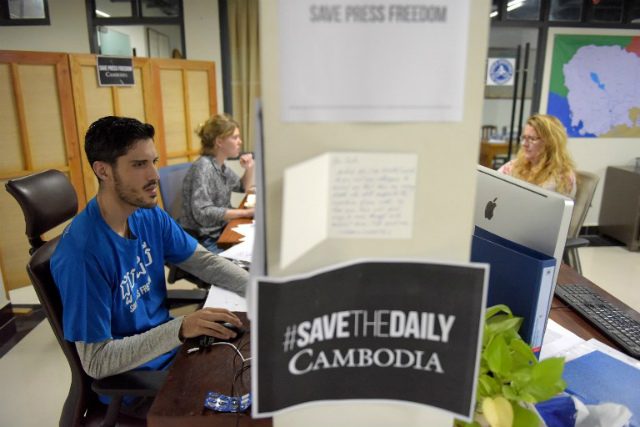

In September 2017, Cambodia’s English-language newspaper Cambodia Daily closed down after 24 years – after being slapped with a $6.3-million tax bill. The paper, which has published reports critical of Hun Sen’s government, said the tax bill was politically motivated.

Indonesia

While Indonesia has a press law that punishes those who attack a journalist with fines of 500 million rupiah and up to two years in prison, attacks against media workers continue to go unpunished. According to the Jakarta-based Alliance of Independent Journalists, there were 78 incidents of violent attacks on journalists in 2016, nearly double the number of incidents recorded in 2015. Of those 78 incidents, there were only a few cases where the attackers have been punished.

Human Rights Watch also reported an atmosphere of fear and self-censorship in many newsrooms – particularly in provincial capitals and smaller cities in Indonesia – due to abuses by security forces and local authorities.

Media access to the provinces of Papua and West Papua also remain difficult places to access for both Indonesian and foreign journalists who want to report on corruption and abuses there.

Laos

Laos exercises control over the press, with only 3 out of 40 television channels privately-owned. Journalists face the threat of being accused of defamation and misinformation, which are criminal offenses that carry long prison terms. They may also be jailed for reporting news that “undermines or weakens state authority.”

Because of the self-censorship practiced by newsrooms to avoid harassment by the state, many Laotians are turning to social media for information. But a 2014 law introduced criminal penalties for internet users publishing information meant to discredit the government. A 2016 decree also compelled foreign media in Laos to submit their content to the government for censorship before publication.

Malaysia

Malaysia’s Sedition Act and defamation charges remain threats to journalists, particularly to media outfits deemed critical of the government. In 2015, the government of Prime Minister Najib Razak targeted journalists covering the corruption scandal involving the national wealth fund, 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), which implicated the prime minister.

Reporting on the 1MDB controversy also prompted criminal defamation proceedings against 4 news outfits, according to non-governmental organization Freedom House. In 2016, the Malaysian Insider news website was forced to close amid the government clampdown on independent media.

Myanmar

For decades, Myanmar was known as one of Asia’s most repressive countries for media. Under decades of authoritarian military rule, journalists were forced to be subjected to censorship to avoid jail terms. Since Myanmar began its transition from a military dictatorship to democracy, press freedom in Myanmar has improved. In 2012, pre-publication censorship was ended, and a mass presidential amnesty saw many journalists jailed on anti-state charges freed from prison.

But journalists continue to face threats when reporting on sensitive issues such as investigative coverage of the military, rebel groups, or the Rohingya ethnic minority. Access to the Rakhine region is limited, where human rights groups claim widespread abuse by the military against ethnic Rohingya civilians persists.

Also problematic in Myanmar’s laws is the Telecommunications Law, which punishes defamation over communications networks with a 3-year prison term. This law is increasingly being invoked to stifle online criticism against the government and the military.

Philippines

At the start of his presidency, President Rodrigo Duterte had been continuously attacking the press, accusing the media of publishing false and malicious reports about his government. Just weeks after winning the May 2016 polls, Duterte triggered criticism when he said corrupt journalists were legitimate targets of assassination.

Even as he encouraged his supporters not to threaten journalists, Duterte himself has frequently issued thinly-veiled threats against various media groups, such as newspaper The Philippine Daily Inquirer, television network ABS-CBN, and Rappler. These threats have been magnified by an online propaganda machine fueled by trolls and bloggers who have been awarded with either government posts or consultancies.

Duterte has lashed out at journalists for allegedly “misinterpreting” or “taking out of context” his controversial statements and rude jokes, even as transcripts and audio or video recordings corroborate media reports.

While urging media to always tell the truth and “never lie,” his own allies are accused of peddling fake news and circulating false information repeatedly debunked by the targets of his rebukes.

Singapore

Singapore’s government responds to criticism from the press through legal actions, invoking harsh criminal defamation laws to silence critical media outlets. Defamation and sedition lawsuits can mean up to 21 years in prison for those convicted.

The Newspaper and Printing Presses Act, the Defamation Act, the Internal Security Act, and articles in the penal code allow Singaporean authorities to block news deemed to threaten public order or national security, among others. The Media Development Authority also has the power to censor content both in traditional and online media.

Journalists are likewise restricted by the topics and issues that are considered off limits for the press, which are referred to as “OB (out of bounds) markers.” Media critic Salil Tripathi noted that the OB markers are not clearly defined, and that journalists have to figure out what can and cannot be said.

Thailand

Press freedom worsened in Thailand since the 2014 coup that installed the junta led by General Prayut Chan-ocha. Journalists have been subjected to increased surveillance by authorities, with media workers summoned for questioning or arbitrarily detained. Several laws punish the publication and circulation of news critical of the monarchy and military junta.

Since the 2014 coup, dozens have been charged under Thailand’s lèse-majesté laws, with the penal code punishing anyone who “defames, insults, or threatens the King, Queen, the Heir-apparent, or the Regent” with up to 15 years in prison. The Computer Crimes Act also punishes the online publication of false content that threatens the public or national security.

Vietnam

The government owns almost all of Vietnam’s media outfits, and censorship of sensitive topics is common. The country’s criminal code prohibits speech critical of the Communist Party of Vietnam. The government invokes Article 79, 88, and 258 of the criminal code, under which “anti-state propaganda,” activities aimed at “overthrowing the state,” and “abuse of democratic freedoms” to undermine state interests are punishable with imprisonment.

In 2011, a decree was issued to restrict the use of pseudonyms and exclude bloggers from press freedom protections. As citizens turn to the internet for information, many bloggers and citizen journalists have been arrested. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.