SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

AT A GLANCE

- In the Philippines, the obsession with beauty pageants is culturally entrenched

- National pageants are a multi-million peso lucrative industry, attracting hordes of sponsors and promoting Philippine designers and make-up artists

- Feminists say the country’s fixation with these contests is harmful to women because it sets unrealistic standards of beauty and promotes gender inequality

Part 1 of a 2-part series

MANILA, Philippines – On a vast stage with flashing lights and blaring music, 30 women in haltered gold lamé dresses twirl and prance in choreographed unison.

Their long hair bounce on their shoulders, smiles big and wide, as they sway along, raise their arms and shake their hips – all on their sky-high heels. They dance together to “Manila Girl”, like they’re in a noontime show.

In their sparkling gowns and fancy suits, the audience – actors, singers, and some politicians including a former president – all lap it up. The rest of the crowd cheer, chanting names and carrying banners plastered with photos of the women’s faces.

Welcome to yet another beauty pageant, a regular spectacle in the Philippines which often draws crowds by the hundreds.

In the next few hours, the women will go from wearing their bright metallic dresses to just a bikini, before reappearing on stage in long evening gowns – showcasing themselves from every angle.

A handful will then make it through to the final stages of the contest and answer questions from the judges in less than a minute, and at the end of the night, 4 grueling hours later, one woman will wear a crown.

At the Philippine International Convention Center plenary hall on June 24, a historic building that is often used to welcome heads of state, the Miss Manila Beauty Pageant is in full swing.

In the Philippines, beauty pageants are a national obsession.

Many young girls are urged by their parents or older relatives to join beauty pageants because of the prestige that comes with winning. Filipinos are exposed to beauty contests at a young age due to their ubiquity – with pageants being a staple in every community.

“In the Philippine setting, pageants are an institution that will not fade away. Every sitio, barrio, barangay, local town and city holds and conducts its own beauty pageant yearly. It’s part of our culture,” Pawee Ventura, a pageant follower and frequent judge at international pageants, told Rappler in 2013.

International pageants are an even bigger deal. Weeks before major international beauty contests, news headlines are filled with updates about preparations of candidates, their gym routines, their diets and the designers who are creating their gowns.

Social media is abuzz with opinions on what the Philippine representative should work on, with passionate fans often bickering about their predictions. The candidates too are under immense pressure, and are put under strict diets, training schedules, and press engagements.

How did this all begin? Filipinos’ fixation with beauty pageants can be traced all the way back to colonial history.

“Our passion for beauty pageants could probably be traced back [to] the Spanish times. The traditional Santacruzan festival demands that the most beautiful lass in the barrio should be the Reina Elena. That in itself was a form of beauty pageant and that could be the roots of our love affair with beauty pageants,” Ric Galvez, founder of leading pageant website Missosology.

This was further stamped on the Philippine consciousness during the American period through Carnival Queens, a title bestowed on the winner of a beauty and talent competition.

Things levelled up in post-colonial Philippines, as the stunning Gloria Diaz won Miss Universe in 1969, the country’s first major crown.

It has since become a source of pride in a country riddled with poverty. Philippine bets won Miss Universe 3 times in 1969, 1973 and 2015; Miss World once in 2013; and Miss International 6 times in 1964, 1970, 1979, 2005, 2013, and 2016.

Aside from this, bringing the most presitigious pageants to the country also helped spur further interest.

“Having hosted the Miss Universe pageant not just once but thrice could have further given our beauty appetite a boost. Today, beauty pageants are alive and well in our country. Any barrio fiesta would be boring without it,” said Galvez.

Pageants are so embedded in Philippine culture that there are contests for children, LGBT communities, and senior citizens. Even overseas Filipino workers host their own pageants in communities abroad.

Taking pageants seriously is something unique to the Philippines, compared to most other countries.

The Philippines’ consistent top finish at the Global Beauties’ Grand Slam Ranking is evidence of this. Global Beauties, a Brazil and Panama–based website that analyzes international beauty pageants, ranked the Philippines on top of its annual Grand Slam Ranking two years in a row – in both 2016 and 2017.

The rankings are tabulated based on points earned for every country’s top placing in major global pageants.

“Philippines consolidates its position as the planet´s number 1 beauty pageants´ powerhouse,” the website read, after it announced 2017’s final standings.

The Philippines finished with 115.6 points, far ahead of second-placer Venezuela (104.7) and Colombia (76.3).

“Filipinos are unabashedly appreciative of female beauty. We are perhaps the most liberal nation in Southeast Asia and we see feminine beauty as empowering rather than a threat,” Galvez said. “Our culture is more aligned with Latin America rather than with our neighboring nations.”

Indeed, the top 10 boasted of 4 Latin American countries, with only the Philippines and Thailand from Southeast Asia. Six of the 10, including the Philippines, were unsurprisingly former Spanish colonies.

But who exactly benefits most from these pageants?

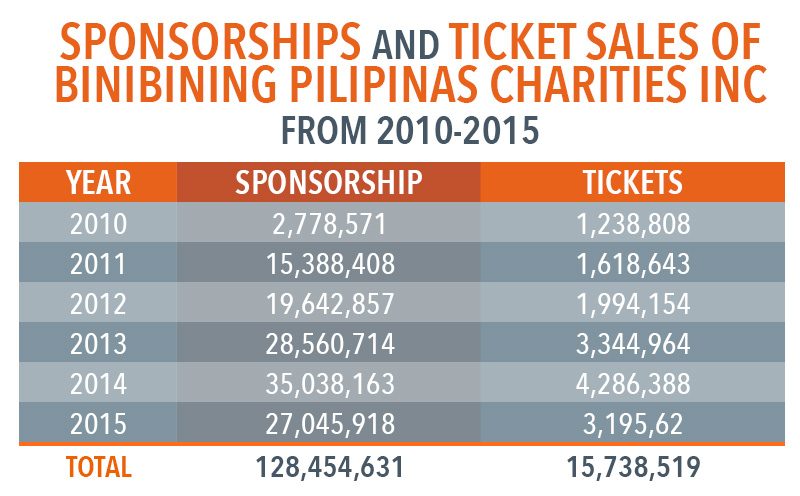

Financial statements submitted to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) by the Binibining Pilipinas Charities Inc – the organizers of the country’s biggest pageant – emphasized how lucrative pageants are.

Between 2010 to 2015, the years with the latest documentation, sponsorships varied between P2.78 million (about $54,587) and P35 million (roughly $688,225). Over those 6 years, sponsorships reached a whopping P128,454,631 ($2,523,125).

Ticket sales also raked in a lot of funds, varying between P1.24 million ($24,333) and P4.29 million ($84,190). It totaled over P15.73 million ($309,127).

“It is safe to say that the pageant industry in the Philippines is a multi-million peso industry,” Galvez said. “For pageant owners, there are always sponsors that are very willing to shell out substantial amount of money because there is widespread interest in beauty pageants.”

Galvez pointed out, there are other winners in the industry too.

“From small-scale couturiers to famous fashion brands such as Michael Cinco or Francis Libiran, our interest in pageantry gave our fashion designers a much-needed boost. Many foreign countries for example have tapped Albert Andrada after his gown was used by Pia Wurtzbach at Miss Universe. The same is true for several Filipino pageant trainers and make-up artists,” he added.

BPCI on its website claims it “donates all its earnings to a string of orphanages in Metro Manila including daycare centers, in cooperation with the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD).” The benefits are clearly plenty for recipients, organizers, designers and sponsors.

But what about the women?

Kristel Herrera, 23, is a first time pageant contestant. She is a singer by profession, but was convinced by some elders to try her luck in Miss Manila. Her dream is to become a model.

The pageant would’ve made the dream easier. The winner of Miss Manila stood to win P500,000 ($10,000) along with a talent contract with Viva Entertainment, which produces some of the country’s biggest stars. Part of the cash prize comes from the pocket of the city’s Mayor Joseph Estrada himself – a common practice in the Philippines, where politicians host and organize pageants for their constituencies.

The pageant is one of the most anticipated local contests in the country, having paved the way for some women to compete on the world stage.

The pre-pageant events are tedious, with back to back appearances. Upon acceptance as a contestant, the women are housed in Manila Hotel, their schedules strictly dictated, up until coronation night. The preparations include media presentations, training on walking, make-up and Q&A, charity work, and photo shoots.

“I’ve been preparing. Like I’m reviewing some old news about Manila. I’ve been dieting, of course. One of the most intimidating process of being a model is the diet so it’s one of my preparations. And the walking and the talking as well,” Kristel told Rappler.

She said she eats just one egg in the morning, and one before bed, and “lots of green salad” and turmeric tea in between.

Asked what she thinks make her stand out, she doesn’t say her physical appearance. Kristel is slightly shorter than most of the girls.

“I can sing. I have studied a lot of history of Manila so maybe I could answer a lot,” she said.

Ten days before pageant night, at the presentation of the contestants to the media, Estrada said he revived the pageant after his return as mayor, “as a symbol of the return of beauty and energy of Manila.” He called the pageant the “highlight” of the city’s 446th anniversary of Manila’s founding.

The 80-year-old – who is also known for his womanizing and his numerous marital affairs – then took the opportunity to talk about how the pageant benefitted him.

“I must admit that this must be one of the most enjoyable benefits of being mayor. Lagi akong dinadalaw ng mga magagandang Pilipina. Nawawala tuloy ang aking problema. (I am always visited by beautiful Filipinas. So my problems go away).”

The audience laughed heartily.

It is this sort of objectification of women – of seeing women as sources of pleasure – that makes some people uncomfortable about pageants, and claim they are merely an excuse to ogle women.

For these reasons, in countries outside the Philippines, there has been a backlash against beauty pageants.

A town in Argentina has since banned them altogether, arguing they are “sexist” and “encouraged an obsession with physical beauty and illnesses like bulimia and anorexia.”

In the United States, critics have slammed its existence in the 21st century, for adhering to traditional standards of beauty and virtue for women – like requiring contestants to never have been married or pregnant.

Peru also made headlines last year when their national pageant asked women to announce statistics of violence against women in the country, rather than their physical measurements of bust, hip and waist.

In France, the Senate approved a ban on pageants for young girls, with proponents arguing, “It is extremely destructive for a girl between the age of 6 and 12 to hear her mother say that what’s important for her is to be beautiful…We are fighting to say: what counts is what they have in their brains.”

Dr Mina Roces, a professor at the University of New South Wales who has focused her research on women’s history in the Philippines, noted that pageants are harmful for women because they promote unrealistic standards of beauty that only few can achieve.

“What’s harmful is that it fits a certain scheme,” Roces said pointing out height requirements and ideal body types for pageants.

“The fact that there’s a stereotype that’s unrealistic for many people. And if it becomes prescriptive, you would feel less of a fulfilled person if you don’t fit the ideal. That would be harmful.”

An Asia Sentinel article raised this concern as well, in an article titled, “Miss Universe: Western Mom or Dad Needed.” It points out that in Southeast Asia, those who often do well are of mixed heritage.

After Pia Wurtzbach’s 2015 Miss Universe win, the article pointed out that “Asian viewers cheering yet another victory for a Southeast Asian contestant in the rival Miss Universe and Miss World contests might do well to ponder who is chosen to represent their countries and why.”

“Even a cursory analysis of the chosen ones indicates characteristics which are atypical of their nations. The first is a preference for semi-Caucasian features, notably of eyes and nose. The second, a preference for skins much lighter than the national norms. Third, they must conform to the notion that tall is beautiful.”

Wurtzbach is half German.

“The bottom line of all this is that however well formed, beguiling, charming and intelligent you are, if you have a brown skin and are only 160 cm tall or less (well above average for the region) you have zero chance of winning a national Miss contest in Asia, let alone one run by Western organizations, however hard they try to appear inclusive,” it said.

Feminist and artist Nikki Luna was more blunt in her disapproval of pageants.

“I don’t support beauty pageants but definitely I don’t have anything against the women who join these,” she told Rappler.

“There’s nothing empowering about beauty when beauty is defined only in standards that are structured by society. A patriarchal society. Such as thinness. Perkiness. Youthfulness. Being ageless.”

“In beauty pageants, it’s really more a display of the flesh. It’s the measurements. It’s the height. You cannot enter a beauty pageant if you’re short, if you’re a mother, if you’re pregnant. There are a lot of single mothers. You have to be certain things to be that kind of woman.”

Are these arguments enough to deter Filipinos from joining and watching beauty pageants?

Roces said the Philippines’ obsession with pageants is so culturally entrenched, making it hard for FIlipinos to simply leave it altogether – and to realize how it hinders women’s empowerment. Beauty, she said, is tightly linked to the image of the ideal woman in the Philippines, more so than the West.

Beauty is so well rewarded in the Philippines, that beautiful women – and beauty queens – enjoy fame and power. She said in the West or in other countries, beauty queens are not able to translate their beauty titles into power – unlike here, where former beauty queens have gone on to become influential actresses and politicians, among others.

“People get prestige from having a beauty title. And every Filipina wants to be beautiful because it means she’s virtuous and she’s powerful,” she said.

“What makes the Philippines unique, let’s say with the West, is there’s a connection between beauty and power. Only for the female. Not for the men. For the men, it’s virility and power that’s connected.”

This overemphasis on physical attributes for women but not for men further promotes unequal treatment and perception between genders.

Roces said that the only way pageants would be less popular in the Philippines, is if Filipinos internalized gender inequality, and became determined to resist it.

“[Beauty pageants] are definitely a challenge for feminists,” she said. “We need to give women a feminist consciousness. It shouldn’t only be about beauty….to expand the definition of women to be more than just beautiful, I think that’s what feminists need to do.”

As the night starts to wind down at the Philippine International Convention Center, special awards are handed out to some of the women.

Best in swimsuit. Best in evening gown. Best in talent.

Kristel wins nothing.

She is hard to see from the audience, relegated to the last row, all the way in the back, where the stage lights barely reach her.

She claps graciously and keeps a smile on, as the prizes are awarded.

And then, the announcement of the top 15. The crowd favorites are expectedly called. They walk towards the front of the stage. Soon, there are only 3 spots left.

Kristel does not make the cut.

She and the bottom 14 are ushered off the stage, while the remaining 15 wave to the crowd.

After the contest, she tells Rappler she is ready to go home and rest. She is feeling sick, she says, her health taking a toll from the back-to-back appearances and training in the days leading up to the contest. This, plus the whirlwind of emotions.

Asked how she felt about her early elimination, Kristel says she tried not to expect too much to save herself from dissapointment – before conceding she couldn’t help but feel upset.

“Well I just, maybe I just cried a little bit earlier because I saw my mom. My mom is sick. But then when I didn’t get to the Top 15 I told her to go home so she could rest,” she says.

Kristel says she may return to compete again – while she still fits the standards of beauty set by the organizers. And society.

“Yeah, why not,” she says. “I’m not getting any younger though, I’m 23. I think the limit is just until 25.” – Rappler.com

CONCLUSION: Are beauty pageants sexist or a celebration of feminity?

*$1 = P50.9

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.