SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – A landmark bill that would implement the peace deal between the government and rebel group Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) is pending before Congress.

The proposed law would abolish the current Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) and install a new one with more powers, more resources, and possibly a larger territory. It will be called the Bangsamoro.

Senators and members of the House of Representatives and the Senate have indicated that certain provisions of the proposed law will be deleted and amended due to concerns over their constitutionality and implementation.

Amid talk of watering down the law, especially after the Mamasapano clash, what makes the Bangsamoro different from the ARMM?

Here’s a rundown of 14 key features of the Bangsamoro compared to the ARMM.

1. How the law was crafted

Republic Act 9054, the law that amended the ARMM as it is now, was supposed to have been based on an earlier peace agreement between the government and rebel group Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) signed in 1996. But when the bill went to Congress, the MNLF had no participation in crafting it, resulting in a measure that the MNLF continues to believe abrogated the peace deal.

This time around, the MILF is involved in crafting the BBL through the 15-member Bangsamoro Transition Commission (BTC). MILF chief negotiator Mohagher Iqbal led the BTC, which wrote the first draft of the law that was reviewed by Malacañang then submitted to Congress.

2. Form of government

Unless amended by Congress, the passage of the BBL will see the ARMM shift towards a parliamentary form of regional government – the only one of its kind in a country that has a presidential unitary system.

In the ARMM, residents cast their votes for the regional governor and the vice governor, as well as 3 members from each district for Regional Legislative Assembly (RLA) – the body tasked to pass laws for the region. There should also be at least 3 sectoral representatives but this was only implemented when Aquino made such appointments in 2012.

Aside from having his own cabinet, the ARMM governor also has an advisory body known as the Executive Council, which is composed of 3 deputy governors representing Christians, indigenous peoples and Muslims, plus the governors and vice governors of each province.

For the Bangsamoro, residents would instead vote for their representatives in the parliament. The elected representatives would choose a chief minister among themselves.

The Bangsamoro Parliament would be composed of at least 60 representatives with the following composition:

- 40% district seats

- 50% sectoral representatives

- 10% reserved seats – 2 seats for non-Moro indigenous communities and one seat for women

The Executive Council would transform into a more comprehensive Council of Leaders composed of the chief minister, provincial governors, mayors of chartered cities, and representatives from the non-Moro indigenous communities, women, settler communities, and other sectors.

The yet-to-be-constituted Bangsamoro parliament will determine how the elections for sectoral and other representation in the parliament will be conducted.

Another unique position in the proposed Bangsamoro is the Wali or titular head, which would only have ceremonial functions. The parliament appoints the Wali.

3. How the autonomous regional government will work alongside the central government

Like the ARMM, the Bangsamoro government will continue to be under the general supervision of the President of the Philippines.

The BBL, however, introduces a concept that recognizes the “aspiration” of the Bangsamoro people towards real autonomy – the concept of asymmetrical relationship.

Supreme Court Justice Marvic Leonen, former chief government negotiator, defined asymmetrical relationship in the case of the League of Provinces of the Philippines versus DENR to mean that “autonomous regions are granted more powers and less intervention from the national government.”

How will this concept be implemented in the Bangsamoro? In a number of ways.

RA 9054 only defined the 14 powers (Article IV, Section 3) that would remain with the central government. The BBL, meanwhile, specified the powers that would be devolved to the region into the following categories (Article V):

- 9 reserved powers for the central government

- 57 exclusive powers for the Bangsamoro

- 14 concurrent powers between the two

RA 9054 stresses the power of the President to suspend the ARMM governor for up to 6 months for violating the Constitution or any other laws.

In the BBL, there is no mention of the same set of powers. Instead, the bill provides for the creation of an “Intergovernmental Relations Body” to be composed of representatives from the Bangsamoro government and the central government that will “resolve issues on intergovernmental relations.” In case the body fails to resolve issues, the President will make the decision.

4. Block grant

Under the ARMM, regional government officials are required to defend their budget every year before Congress just like any other line agency, making the supposed autonomous region still dependent on the national government for funding.

The President has the power to suspend, reduce or cancel funding if the ARMM fails to account for the funds quarterly. The Secretary of Finance also has the power to suspend or cancel the release of any or all funds if more than half of the funds released remain unaccounted for 6 months after an audit is conducted.

To make the Bangsamoro – as a superior LGU, more fiscally autonomous, the systerm for sharing resources will be changed. It will have a set-up similar to the internal revenue allotment of local government units, where a set amount based on a formula is automatically appropriated every year.

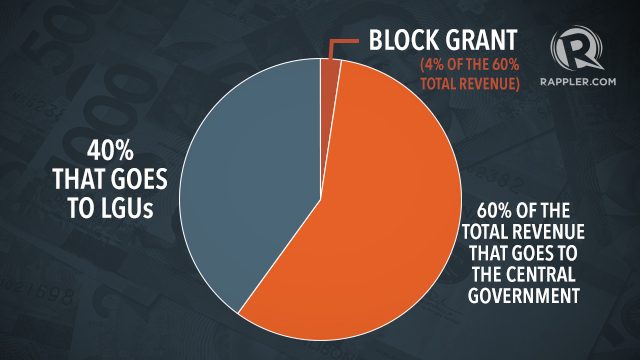

This will be called the annual block grant, an amount that will be taken from the national government’s share in the total revenue collection.

The fomula for the block grant is 4% of the 60% of the total revenue collection that goes to the central government – representing the proportion of ARMM residents to the national population.

The remaining 40% that goes to LGUs would remain untouched.

With this, the regional government will enjoy a regular release of funds like other LGUs in the country and would no longer have to go to Congress to defend the budget.

There is an interesting feature anchored on the block grant. While it is automatically appropriated, the BBL also includes the possibility of deductions. Once the Bangsamoro is up and running, revenues from additional taxes devolved to the Bangsamoro and revenues from the region’s share in government income from the exploration, development and utilization of natural resources collected 3 years before would be deducted from the block grant.

However, the BBL does not detail how the Bangsamoro parliament would prepare and approve the budget for the region. Instead, it will be left for the Bangsamoro Parliament to pass the law that would establish the system.

How would funds be accounted for? The BBL creates an internal Bangsamoro Commission on Audit, which does not prohibit the national COA from auditing the region as well.

5. How wealth will be shared between the Bangsamoro government and the central government; and between the regional government and LGUs

Aside from getting automatic appropriations, the BBL increases the share of the proposed Bangsamoro on national taxes collected in the region and metallic minerals to 75% from 70% in the current ARMM.

It changes the qualification of minerals from “strategic” and “non-strategic” – which government chief negotiator Miriam Coronel-Ferrer has said were political in nature – to the categorical “metallic” and “non-metallic” to prevent future conflict on how revenues from such resources will be divided between the national and regional government.

The ARMM law itemizes what percent of the region’s share in taxes and mineral resources would go to the provinces, cities, municipalities and barangays. The BBL, however, does not and leaves the decision to the Bangsamoro parliament.

6. Bangsamoro identity

RA 9054 dedicated a section to defining tribal peoples and “Bangsa Moro” people:

Article X, Section 3:

(a) Tribal peoples. These are citizens whose social, cultural, and economic conditions distinguish them from other sectors of the national community; and

(b) Bangsa Moro people. These are citizens who are believers in Islam and who have retained some or all of their own social, economic, cultural, and political institutions.

The BBL includes a more comprehensive definition of who the Bangsamoro people are. However, the definition of indigenous peoples does not appear in the BBL.

Bangsamoro people are defined in the BBL as “those who at the time of conquest and colonization were considered natives or original inhabitants of Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago and its adjacent islands including Palawan, and their descendants, whether of mixed or of full blood, shall have the right to identify themselves as Bangsamoro by ascription or self-ascription. Spouses and their descendants are classified as Bangsamoro.”

7. Justice system

The ARMM laid the groundwork for the operationalization of Shari’ah courts in Muslim Mindanao through apellate courts, district courts and circuit courts. Shari’ah courts only have jurisdiction over Muslims in the region and will not be applicable to non-Muslims.

The BBL takes this one step further and creates a Shari’ah High Court.

While the ARMM only prescribes that the regional government “may formulate” a Shari’ah legal system, the BBL defines the jurisdiction of Shari’ah courts in great detail.

Aside from Shari’ah courts, the BBL also establishes a tribal justice system for indigenous peoples, as well as alternative dispute resolution systems. Regular local courts will continue to exist as well.

National laws will continue to apply in the region, and all courts will remain under the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.

8. Bangsamoro waters

The BBL aims to introduce a new concept of regional waters. Elsewhere in the country, only municipal waters are defined since other regions only have administrative functions.

The Bangsamoro waters extend up to 22.224 kilometers or 12 nautical miles from the low-water mark of coasts that are part of the Bangsamoro territory. The jurisdiction over municipal waters will remain under LGUs.

After 10 years, the bill will be reviewed for “enhancements.”

9. Indigenous people’s rights

Both the ARMM and the Bangsamoro laws recognize the rights of indigenous peoples in Muslim Mindanao to native titles, their customs and traditions, and political and judicial structures.

However, both laws also fail to mention the IPRA, passed in 1997 way before both RA 9054 and the proposed BBL were crafted. (Rappler talk: Are the Lumads victims in war and peace?)

The IPRA was never implemented in the ARMM due to the lack of an equivalent enabling law for the region.

Under the BBL, it will also be up the parliament to enact laws on the rights of indigenous communities over natural resources.

Non-Moro indigenous communities will have two reserved seats in the Bangsamoro Parliament.

The BBL also seeks the creation of a tribal university system.

10. Regional Police

The Bangsamoro will not get its own police force as the proposed regional police body will continue to be part of the Philippine National Police. In fact, it will have the same powers and functions under the regional police force contemplated in the ARMM law.

Similar to RA 9054, a regional police board will also be created to perform the functions of the National Police Commission in the Bangsamoro. The BBL mentions how the board will be created, unlike RA 9054.

Almost all powers that the ARMM governor has over the police will be the same in the Bangsamoro. The sole difference is that the ARMM governor can only recommend the head of the regional police while the chief minister can select the head and his deputies.

Some lawmakers are opposed to the provision giving the chief minister operational control and supervision over the regional police following the Mamasapano clash. But a review of RA 9054 shows that this power had already been devolved to the ARMM governor.

11. Armed forces

Both the ARMM law and the BBL allow for the creation of a regional command of the Armed Forces of the Philippines.

This does not mean that the autonomous region can get its own army. Both the ARMM laws and the BBL are clear – regional defense and security will continue to be the responsibility of the central government.

A big difference, however, is the establishment of coordination protocols between the central government and the Bangsamoro for the movement of the military in the region – another provision that lawmakers want to delete post-Mamasapano.

In the current ARMM, the President can send the military to the region if the regional governor does not act within 15 days on any security concerns.

12. Women’s rights

The proposed Bangsamoro government includes more concrete measures for the protection of women’s rights.

The BBL reserves one seat for women in parliament, without prohibiting them from vying for other seats.

It also requires 5% of the total budget to be allocated for gender-responsive programs.

13. Possibility of expanding territory

When RA 9054 was ratified in a plebiscite in 2001, provinces and cities that voted against their inclusion in the ARMM during the first plebiscite in 1989 were included. However, only Marawi City and Basilan, excluding Isabela City, opted for inclusion.

For the Bangsamoro, the plebiscite will be held in the identified core territory but contiguous areas – or LGUs sharing a common border with the Bangsamoro core territory – may join the voting if there is a petition from at least 10% of registered voters asking for their inclusion at least two months before the BBL ratification is conducted.

Those who won’t do so may still get a chance to join the Bangsamoro in the future. These contiguous areas may also opt “at anytime” to join when at least 10% of registered voters file a petition for it and the request is approved in a plebiscite. The Malacañang-convened Citizens’ Peace Council recommended the deletion of this provision to ease concerns about a possible “creeping expansion” of the Bangsamoro territory.

Due to the unique opt-in provision, the BBL also seeks to create a regional branch of the Comelec that will handle all plebiscite or election-related concerns in the region.

14. Transition period

MNLF founding chairman Nur Misuari was elected governor of the ARMM less than a month after signing a peace pact with the Ramos administration in 1996, forcing the MNLF to shift from their rebel underpinnings to governance without due preparation.

With the Bangsamoro, a transition period is envisioned. The MILF will lead a transitional government until the election of the first set of Bangsamoro officials in 2016.

The Bangsamoro Transition Authority will be composed of 50 members appointed by the President. Non-Moro indigenous communities, women and other sectors will be represented, according to the BBL.

The MILF had hoped to have a transition period of 3 years at the start of negotiations but delays in the inking of the peace pact and the submission of the law, as well as the Mamasapano clash have made the timeline tighter.

The House of Representatives is set to vote on the proposed law at committee level on Monday, May 11.

Senate committee on local government chair Senator Ferdinand Marcos Jr, meanwhile, hopes to finish committee hearings by May 25.

Proponents hope that the law would be passed before Congress ends its 2nd regular session on June 12. Lawmakers will report back for work in July for President Aquino’s final State of the Nation Address. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.