SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Dengvaxia scare: How viral rumors caused outbreaks](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/EE328B4909D14547B362513B7A1CE5F5/img/77DF9C8CB2AD4BB4833F085CC2631791/Dengvaxia-scare--How-viral-rumors-caused-outbreaks-January-16-2019.jpg)

Fake news can kill, and the Dengvaxia scare is a perfect example of it.

The Dengvaxia vaccine was a promising solution to the scourge of dengue, a mosquito-borne disease to which hundreds of thousands of Filipinos fall victim each year.

But in November 2017 Dengvaxia’s developer (Sanofi Pasteur) revealed that those inoculated with it were at risk of a more severe form of dengue if they didn’t have it before.

This finding quickly made the headlines and was blown out of proportion. Soon public opinion formed that Dengvaxia killed a number of children who were administered with it.

This rumor persists even if, to this day, no death has been conclusively linked to Dengvaxia, according to the Department of Health (DOH).

In fact, Dengvaxia’s commercial release has recently been approved in Europe and 10 other countries, and foreigners are perplexed by Filipinos’ widespread distrust of it.

But in this article I want to focus on the broader, truly fatal impact of the Dengvaxia scare: Filipino parents today are much less trusting of vaccines in general, resulting in outbreaks of diseases other than dengue, notably measles.

Herd immunity

To fully appreciate the negative consequences of the Dengvaxia scare, you need to understand the economics of vaccines.

Vaccines belong to a special type of good in economics that confers benefits to bystanders who don’t buy or consume it.

The more of your neighbors are immunized against a certain contagious disease, the harder it is for that disease to spread in your community. These extra benefits – known as “positive externalities” in economics – give rise to what’s called herd immunity.

Herd immunity means you need not vaccinate everyone in the population to keep them safe from certain diseases. You need only vaccinate, say, 90% of people and the remaining 10% will automatically be immune even if you don’t give them the vaccine.

But for herd immunity to kick in, a certain threshold must be crossed. Vaccinate fewer than the threshold and the community will stand no chance against the disease (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. Source: Redditor theotheredmund.

Lost confidence

It is this herd immunity that the Dengvaxia scare damaged the most.

Millions of Filipinos now distrust vaccines in general, even those already tried and tested against common diseases like measles, polio, and diphtheria.

In February 2018, the DOH reported that only around 60% of children across the country got their scheduled vaccines, lower than their 85% target.

Later, in August, another study revealed that the percentage of Filipinos who strongly agreed that vaccines are “important” dropped tremendously from 93% in 2015 to a mere 32% in 2018; vaccines are “safe” from 82% to 21%; and vaccines are “effective” from 82% to 20%.

Even basic health services not at all involving vaccines – such as deworming – are reportedly being avoided by parents like the plague.

This widespread loss of confidence, in turn, led to losses in herd immunity in many places nationwide.

Last year measles outbreaks were soon declared in places as dispersed as Davao City, Davao Region, Taguig City, Zamboanga City, Negros Oriental, and Kabankalan City in Negros Occidental.

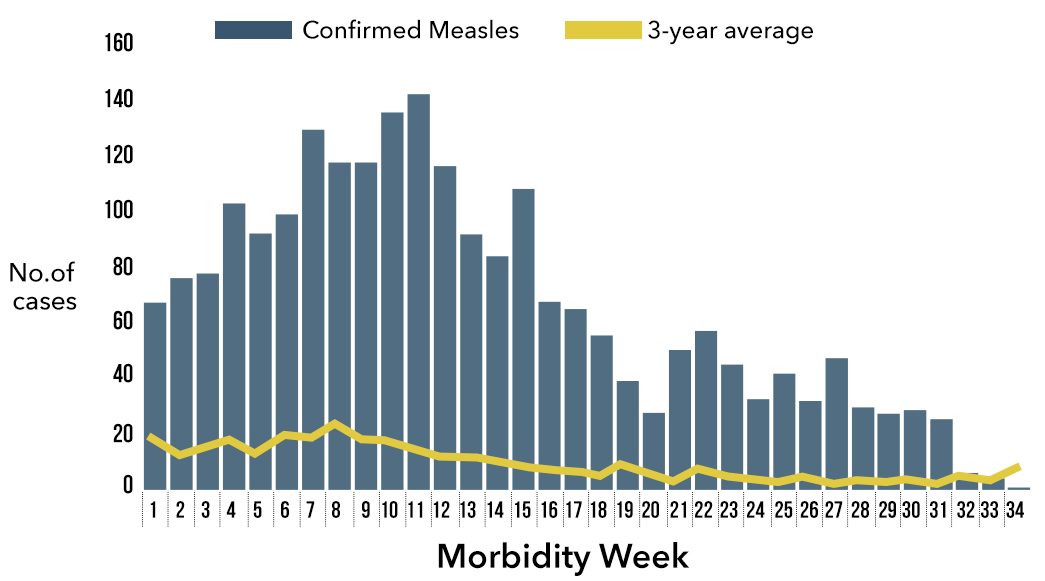

All in all, in the first 11 months of 2018, the country saw a whopping 467% increase in the number of measles cases from the same period last year. Figure 2 below illustrates the glaring surge of confirmed measles cases from January 1 to August 25, 2018, vis-à-vis the average in the past 3 years.

Figure 2. Confirmed measles cases from January 1 to August 25, 2018. Source: DOH.

Problem and solution

In all this, government was both the problem and the solution.

On the one hand, you have the sensationalized antics of Persida Acosta, head of the Public Attorney’s Office (PAO), whose clients were parents of children who supposedly died of Dengvaxia.

Also at fault is Erwin Erfe, director of PAO’s forensic lab, who supposedly deduced Dengvaxia’s fatal effect from observed patterns of internal bleeding, enlarged organs, and deaths within 6 months of receiving Dengvaxia.

Out of these findings, charges of reckless impudence resulting in homicide were filed against at least 39 people, including officials of the past administration. Acosta later revealed that President Rodrigo Duterte himself recommended that these cases be upgraded to murder instead.

We do not wish to belittle the grief of the aggrieved parties, but these cases perfectly illustrate the so-called “post hoc fallacy:” just because Y happened after X doesn’t mean that X caused Y.

Hence, just because the kids died after getting Dengvaxia does not necessarily mean that Dengvaxia caused such deaths.

Independent medical experts later found that the children’s deaths were due to dengue and other factors, and not at all conclusively due to Dengvaxia.

Because of such fallacious claims, another arm of government, the DOH, has since been in damage-control mode.

The public trust in vaccines that took them decades to cultivate at the grassroots level was erased by viral “fake news” peddled by their colleagues in government.

Sure, myths about vaccines are nothing new. In other countries people mistakenly think that vaccines cause autism (there’s also no evidence for this) and that vaccines are supposedly an American tool to sterilize Muslim women (a myth peddled by the Taliban and Boko Haram).

But it is precisely pernicious myths like these that serve as some of the biggest obstacles to our country’s progress and bring needless suffering to our people.

Worse than it needed to be

We don’t know yet the full extent of Dengvaxia’s impact on the children administered with it.

But arguably more damaging than the vaccine itself are the myths and misconceptions that spread about it. Through a combination of fear-mongering, playacting, and politicking, some government officials clearly made the situation worse than it needed to be.

What’s more worrisome is that the Dengvaxia scare only compounds Filipinos’ already high level of skepticism and anxiety when it comes to science and its impact on society.

Data show that almost half of all Filipinos (48%) agree with the proposition that “overall, modern science does more harm than good.”

Because of disinformation episodes like the Dengvaxia scare, our nation’s fight against fake news is more high-stakes than most people realize. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.