SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Let’s call them “Crisis Managers Anonymous.”

Let’s call them “Crisis Managers Anonymous.”

Once a year, they get together outside the United States rotating through different cities and continents. It’s a unique blend of US government intelligence and analysis with private sector crisis management and risk assessment. Simply put, these are the crisis managers of America’s top Fortune 500 companies (ISMA or the International Security Management Association) working with OSAC, or the US State Department’s Overseas Security Advisory Council.

For two and a half days in Singapore, more than 200 experts networked and shared best practices and lessons they’ve learned. Many in the room handled some of the worst crises in the world – from Liberia to Haiti to Japan. Discussions were lively, precisely because much of it was personal. These men and women save lives and a lot of money.

I can’t tell you their names nor the companies they work for. The entire conference was placed under Chatham House Rules, which means “participants are free to use the information received, but neither the identity nor the affiliation of the speaker(s), nor that of any other participant, may be revealed.” This encourages greater openness, which in turn helps keep conversations down-to-earth, real – and, ultimately, useful.

Plenary sessions were interesting, but they were far surpassed by real sharing outside the hall. Unlike many conferences, these crisis managers stayed and networked during all meals to tap the collective knowledge of their peers.

Addict, prostitute

One Asian female executive for a Fortune 500 firm told me about her experiences masquerading as a drug addict, when her company worked closely with the intelligence group of a Southeast Asian nation. Another time, she went undercover as a prostitute. Feisty and articulate, she was candid about what went right and what went wrong in dealing with transnational crime.

Another emphatically argued that “resource scarcity stands to become the major driver of instability and interstate conflict in the coming decade.”

One of the crisis managers during the Fukushima tsunami crisis explained why these conversations are important.

It’s the crisis managers’ version of Alcoholics Anonymous – where explaining how to conquer real life challenges helps both the person sharing and the group listening. They’re honest and try to make real connections because when a crisis hits their country or their company, these are the people they turn to for help. They benchmark, share and help guide each other.

“It’s about communications,” said a manager who spoke about the uncertainty of decision-making when the people who had to manage the disaster had families they were worried about. “Talk to each other, and do it early. Talk to your people openly and honestly.”

Some companies only offered evacuation from Fukushima to key people, faced with revamping corporate rules as the crisis was breaking. Transparency when everything is uncertain helps maintain confidence, said another manager. “We actually did offer relocation to anyone who wanted it, but the repercussions of that are still being felt today,” he added on how to deal with families of employees. “There is still a great deal of resentment about the way people were treated.”

The Japanese tsunami was the most expensive natural disaster in history with more than 20,000 people dead or missing, according to the speakers.

Many said they had crisis plans for an earthquake. Others said they planned for a tsunami. Still others said they even went as far as a nuclear disaster, but no one in the room planned for all 3 simultaneously.

Social networks

While handling Fukushima, one of the speakers described “social media for security professionals” and how he was swamped with trying to follow responses. “It’s very difficult to take notes while you’re managing a crisis,” he added.

Which brings us to how the two-and-a-half day conference began: my presentation on how terrorism spreads through social networks and the new frontier for battle – social media.

I thoroughly enjoyed speaking to this specialized group. My presentation used the title of my upcoming book – From Bin Laden to Facebook: How Terrorism Spreads. Using social network theory, I explained how ideology and emotions combined into a “jihadi virus” which spread from the crucible of the Afghan training camps to homegrown groups in other parts of the world, including Southeast Asia.

I showed individual will is no match for group dynamics, helping explain how terrorists are born, and looked at new studies in social network theory that can map the spread of emotions and behavior – like a medical contagion – through society through 3 degrees.

Using practical applications in real-world campaigns, I outlined the next battleground: the Internet, looking at the growth of jihadi websites and social media accounts on Facebook and Twitter.

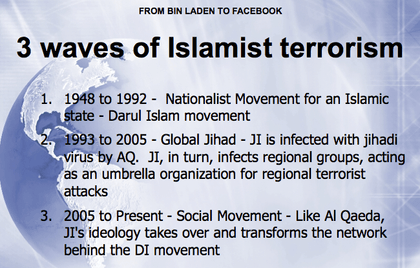

Through it all, I traced how the major terrorist attacks in Southeast Asia emerged from only one social network in Indonesia, which began decades before Al-Qaeda even existed. In 1948, the Darul Islam network in Indonesia formed as a nationalist movement for Islamic sharia law as a way of life.

There were 3 waves of evolution and regeneration of the same social network, an analysis supported by the next speaker, Brig Gen Muhammad Tito Karnavian, Indonesia’s deputy chief of its National Counter Terrorism Agency (BNPT) and the celebrated commander of its highly successful police counterterrorism unit, Detachment 88. He agreed to be quoted for this piece.

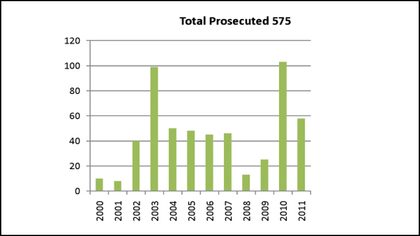

Tito outlined the terror networks in Indonesia showing them before and after 2010, when Indonesia had the largest number of arrests since the deadliest Bali bombings in 2002. Since then, Indonesia has arrested nearly 700 terrorists and prosecuted nearly 600 in its courts system.

Tito broke the evolving Darul Islam network further into two: the JI (Jemaah Islamiyah) and the NII (Islamic State of Indonesia) strands. He spoke about how the network has reconnected with others outside Indonesia, how authorities have failed to “contain the spread of radical ideology” and how the release of former JI members from prison in 2007 only brought many of them back to planning and carrying out terrorist attacks.

Devolved power

From terrorist networks, discussions moved toward social networks and social media, which accelerates the spread of emotions and information across borders. I could feel growing excitement but also great fear and distrust in the room.

One analyst said, “the power of political messaging is devolving – or evolving – to civil society. This is very disruptive if it’s the ‘emerging un-civil society’ that spreads messages of hatred and division.”

I spoke about Facebook’s unprecedented power: for the first time in human history, one platform connects more than 900 million people, spreading ideas and emotions virally, changing business models, the people who use it and the world we live in.

I asked how many people in the room didn’t have Facebook accounts, and nearly a quarter of the room raised their hands. In the last two years of speeches I’ve given around the world, that is the largest number without Facebook I’ve had in a room. It made sense though, they fit the statistics of those least attuned to the social media craze: men in their 50’s.

What was different though was the feeling in the room: nearly all who spoke wanted to know how they could understand and harness this tool. One seriously asked, “how do we begin?”

That, perhaps, is the greatest realization of the conference.

For operations managers used to intricate planning and simulations with advance teams and equipment, there was a feeling of surprise and anticipation. The social networking that allowed these crisis managers to do their jobs better brought them to the greatest tool of all – social media.

I look forward to seeing how they use this powerful platform for security, risk reduction and crisis management. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.