SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

For many in my generation – those born in the ’60s and were young adults in the ’80s – EDSA is so much more than those four dramatic days in February 1986. EDSA was a social milieu defined by the peak and collapse of the Marcos dictatorship and the re-birth of democracy in the country. EDSA was a series of shared and individual experiences; a collective core memory that continues to influence my generation’s views and claims on Philippine politics and society.

EDSA as social milieu is a collective core memory but for sure, members of my generation will have different experiences of this milieu and, therefore, will have different stories to share. This is just one person’s story. I am telling my story now because I am getting old and my memory is starting to fail me. I believe personal stories make up the EDSA story and so these stories have to be told.

My EDSA story has to do with three bits of memory: (1) college life in Ateneo (2) political prisoners, and (3) workers and trade unions.

College life in Ateneo

I entered Ateneo as a college freshman in June 1983, just two months before Ninoy Aquino was killed. I was a wide-eyed “probinsyana” back then – a Cebuana – who didn’t know or care much about politics. I had come to Ateneo largely because I wanted to try living away from home. My parents had agreed to let me study in Manila on two conditions. First, that I would find a course that was not offered in any university in Cebu. This was easy, thanks to the Legal Management program which was a new course offering back then. The second condition was that I would not go to the University of the Philippines (UP) because I might end up an activist. This too was easy because I had no plans of becoming an activist. My plan was to become some topnotch corporate lawyer. As it turned out, my family and I were wrong: I would still end up an activist – in Ateneo.

My activism was awakened by the death of Ninoy Aquino. I remember feeling agitated: someone had just been killed for his political ideas. I couldn’t put a name to what had happened but I knew something was wrong.

The following year, when I was a sophomore, I joined Lingap Bilanggo, a student organization that worked with political prisoners. It was a batchmate, Ingeborg del Rosario (who later became our batch valedictorian), who convinced me to join this organization that was led by another batchmate, Manoling Francisco (who later became a Jesuit). Some of my “org mates” are still on campus: Milet Landicho-Tendero who is now Assistant to the Vice President for the Loyola Schools, Jonny Salvador who is now Headmaster of the Ateneo Grade School and Vina Lanzona who is a professor at the University of Hawaii and currently a visiting professor of the Ateneo History department. Our mentors, meanwhile, included Dr. Cristina Montiel of the Psychology Department whose ex-husband was a political prisoner and Fr. Joe Quilongquilong, S.J., then a young Jesuit and now an Associate Professor of Spirituality and President of the Loyola School of Theology.

Political prisoners

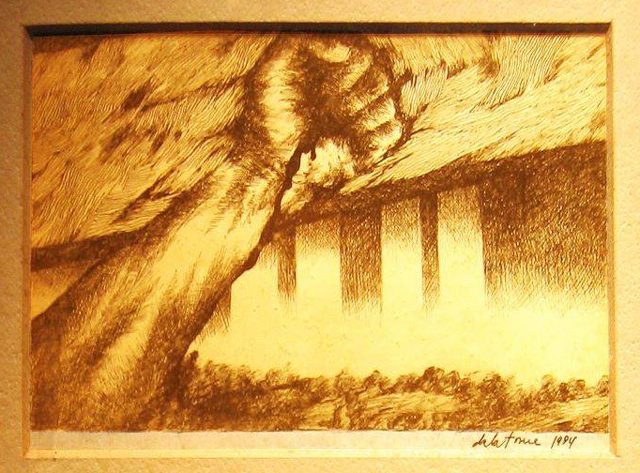

Being a member of Lingap Bilanggo meant spending weekends in jails in Camp Crame, Quezon City and in Camp Bagong Diwa, Bicutan, talking and interacting with prisoners. We would solicit for and bring stuff that they needed – clothes, food, medicine. We would bring their kids to parks. We would help sell artwork or products they made in prison. We would bring cake and sing for them during their birthdays. We did humanitarian, not political activities but I think without being very aware of it, we became highly politicized. In the first place, we were interacting with very political people – social democrats, national democrats: Boyet Montiel, Doris Baffrey, Jovy Labajo, Chut Cellano, Philip Suzara, Judy Taguiwalo, Isagani Serrano, Edicio de la Torre, Gerardo Bulatao, Horacio Morales, to name a few.

More importantly, these weekend jail visits put a name to the phenomenon that previously we could not grasp: injustice. We finally understood Ninoy’s assassination. We finally understood that power with no limits was unjust because it stripped one of human dignity and stripped society of equality – some were free while others were not.

We had first-hand knowledge of how the prisoners were treated. We saw food served in dirty buckets; we heard prisoners being shouted at by jail wardens; we saw families broken because of activist parents in jail and we learned of stories of torture and abuse from the victims themselves.

We would eventually learn that 70,000 Filipinos were imprisoned during Martial Law because of their political beliefs. This knowledge was certainly an eye-opener but our experience was more compelling: because of those jail visits, we were able to attach faces to the concept of injustice and because of that, to this day, I don’t think anyone or anything will ever be able to convince us that a dictatorship is a desirable political regime.

This knowledge about injustice was bolstered by in-classroom discussions. We talked about Martial Law in our Theology of Liberation class, Philosophy classes, even in foreign language class: we would debate about Martial Law and about the U.S military bases – in Spanish. At the time, indignation against the dictatorship was quite visible on campus: it was in the air and we students could feel it, day in and day out.

Ateneo also instituted an “alternative class” program that allowed for off-campus learning. Student participation in Cory Aquino’s Miting de Avance in Luneta on February 4, 1986, for example, was counted as an “alternative class.” Our teachers also didn’t mind that we would attend rallies instead of classes, especially when protests escalated after Comelec voting tabulators walked out of the PICC counting center on February 9 and alleged that the quick count results were being manipulated by their superiors.

And then, of course, there were those days at EDSA.

On the evening of February 22, 1986, we, members of Lingap Bilanggo and other Ateneo organizations belonging to the umbrella group Kaisa sa Diwa at Pananampalataya (KADIPA), were having an overnight seminar on “active non-violence” in a house along Esteban Abada, when parents started calling, asking children to go home because a coup d’etat against Marcos was happening and things could get violent. If I remember correctly, none of us went home. We all proceeded to EDSA. I also remember being at Radio Veritas when soldiers started shooting at the building where press freedom was holding out. Some of the students I was with were members of the Ateneo Rifle-Pistol Team so we felt safe because we had “experts” who knew the distance we had to keep from the shooters.

Workers and trade unions

When Martial Law ended after those four tension-filled days in February 1986, I came to understand two more things. Firstly, that emancipation after the dictatorship was real. We, in fact, had to disband Lingap Bilanggo. The political prisoners were set free and it was a joyous moment to see them leave jail and be reunited with their familes and be reintegrated into society.

Secondly, that power had to be challenged whenever and wherever it wasn’t shared. I understood this through my involvement with Workers College (WC) during my senior year in Ateneo. WC was an NGO in Ateneo that focused on trade union organizing and education. The first union I helped organize was that of our very own campus cafeteria workers. I remember joining a “sit down strike” of these workers in the middle of the campus quadrangle with a placard that said: “Is this what you mean by men for others” (hindi pa uso ang “women for others” noon)? I remember Fr. Raul Bonoan, S.J., the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences back then, calling me out, “What are you doing Ms. Abao?” and I remember telling him, “I’m just helping out po.” Eventually, the workers were recognized as a union (some of them still work at the cafeteria and every now and then would give me free softdrinks).

I graduated from college in March 1987 and by April 1987, I was working for Workers College as a fulltime trade union organizer and educator. I was in good company because other WC-student volunteers also went full time, e.g. Sylvia Pagsanghan-Aldana who now teaches at the Ateneo High School, Ambet Yuson who is now the General Secretary of the Geneva-based Building and Wood Workers International, and, Raissa Jajurie who became a consultant of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and is now a commissioner of the Bangsamoro Transition Commission (BTC).

Our work in WC focused on organizing workers in the textile and garments industry which, at that time, was robust and far from the sunset industry that it is today. There were a number of large factories back then with thousands of regular workers. The labor movement was also quite vibrant at the time (albeit already fragmented). We at WC experienced several labor strikes and collective bargaining negotiations. We also witnessed the decline of factories and the dispersal of the labor force into smaller workplaces. These trends were part of broader shifts in the global and national political economy that became prominent in the late 1990s and onwards: the decline of the manufacturing sector and the rise of the services sector, and, the decline of regular work and the rise of flexible (contractual) labor.

Lessons of EDSA

At this point, EDSA seems like a failed project. We’ve already had five administrations post-EDSA yet long-standing problems like poverty and corruption have not been abated. Moreover, thirty years after EDSA, we are still divided on very fundamental questions: democracy or development? economic growth or social equality? individual prosperity or national progress? These goals are not “either-or” desirables and are not supposed to be at cross-purposes. They are all of equal value. The fact that we are still debating over such fundamental questions reveals the level of (under)development of our democracy.

The failure, I think, lies partly in political leadership, particularly the failure of our political leaders to look beyond symptoms of problems. We have had five administrations and none have really, squarely, addressed root causes. No administration has concerned itself with structural problems such as income inequality, exploitative labor practices, strong political dynasties and weak political parties, non-prioritization of rural development, lack of urban-rural and industry-agriculture linkages, non-prioritization of public education and other programs for human capital development, Manila-centric development, reliance on outmigration as a primary development strategy, and, the unregulated expropriation of our vital, natural resources.

Moreover, citizens have come to distrust the state and rely more on social institutions for their livelihood and security. Social institutions like political dynasties, churches and even underworld networks (Jueteng) have been allowed to become stronger than the state in seeking compliance of citizens. No administration has been bold enough to compel these social institutions to comply with state regulation rather than other the way around.

While EDSA was dramatic, its lessons, to me, will always be about the practical requirements of social change. Change is a complex process and requires continuing struggle. It may be frustrating that after ousting the Marcos dictatorship, the Marcoses are making a comeback. But it shouldn’t be surprising. Of course the Marcoses will compete because the democratic space opened up by EDSA allows for such competition. The Marcoses are just taking advantage of a particular opportunity, that of the May 2016 elections. Thus, the question that we need to ask is not so much why the Marcoses are still around, rather, why Filipinos continue to look to the Marcoses as an option for leadership. What social conditions prodded them to think that Bongbong Marcos, a historical bearer of Martial Law, is a commendable choice for the Vice Presidency? Changing those social conditions could be the only way to stop the Marcoses from reframing history and usurping once again our democratic space.

EDSA as social milieu should teach us not to oversimplify the requirements of social change. Change requires examining immediate problems but also root causes. It requires collective action but also individual courage; energies but also intellect; ideas but also organizations; protests but also proposals. Change requires rupture but also everyday struggle; conflict but also peaceful resolution. It is about politics but also about the economy, society and culture; about solving problems but also about developing visions; about being purposive but also about taking leaps of faith.

Restoring democratic political institutions is not enough. We have to care about the quality of these institutions: are their processes inclusive and are their outcomes beneficial to many? We need to ask: who benefits from our democracy? Who are being strengthened and who are being marginalized? If we do not extend the political democracy we achieved at EDSA to the economic and social spheres, then we waste EDSA.

It’s been thirty years. I am no longer a young activist but an academic approaching middle age. Still, as much as I can, in my own little ways, I try to stay socially and politically involved. I know many from my generation are still socially and politically involved.

To the young adults of today, I invite you to carry on – not to glorify nor to make a repeat of EDSA, rather, to rekindle and breathe new life into its spirit. And to use this rekindled spirit to respond to the needs of your own generation, to shape your own social milieu and to create your own collective core memory. Always, the task of an incumbent generation is to be greater than its past. – Rappler.com

The author teaches Political Science at the Ateneo de Manila University. On February 23, 2016, Ateneo de Manila University held a “story-telling forum” for students and faculty dubbed “Edsa @30: Stories Much Savored, Lessons Worth Saving” to commemmorate the 30th anniversary of EDSA 1. The author was one of the storytellers and this piece is a fuller version of the story she shared during the forum.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.