SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

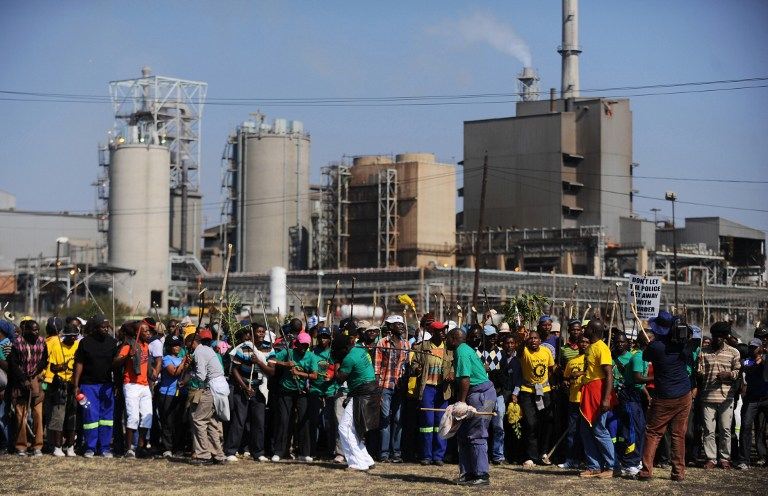

RUSTENBURG, South Africa – Mining unrest has rattled South Africa, but ongoing turmoil has been a hammer blow to the country’s platinum belt, calling into question the future of an entire city.

First was the violence and then came the job cuts.

After months of labor unrest and years of high costs, two top firms around the northern city of Rustenburg are rolling out plans to shut shafts and cut thousands of jobs.

Anglo American Platinum will close three operations here and cut 4,800 jobs from September, a year after the Marikana massacre at neighboring Lonmin mine.

Lonmin — where 34 miners were shot dead a year ago by police — had already mothballed a shaft last year.

For the city of Rustenburg, where mining officially makes up 77% of the economy, the impact could be devastating.

Local businessmen, from utilities consultants like Ben Roothman to street vendors like Tomaz Utui, fear the loss of jobs means the loss of customers.

For every person laid off, a whole household loses its income, so many more thousands are affected, according to Roothman.

“It’s a foregone conclusion that it will have a definite impact on Rustenburg,” he told AFP.

Utui, who hawks snacks, clothes and cigarettes outside Amplats’s soon-to-be-shut Khomanani shaft, sees a dire future if the miners disappear.

“There’s nothing here. We’re not selling if these guys aren’t working.” Already, he said, “These guys don’t have any money.”

According to local Chamber of Commerce head Pieter Malan “at a micro-level the impact is huge.”

“For medium-sized companies who deliver services direct to the mine it’s painful,” he added.

Tough times ahead

Rustenburg was founded 162-years ago after Dutch settlers trekked inland from Cape Town and started farming.

Since the 1920s platinum — now used predominantly in catalytic converters and jewelry — has been mined in the area, known by geologists as the Bushveld Igneous Complex.

Rustenburg was a host city for the 2010 football World Cup and was the country’s fastest growing metropolitan area in that year, according to government figures.

For the moment the city is still growing at a clip.

Modern housing complexes are springing up around the city and the region’s luxury resorts and game reserves attract tourists in their droves.

With around 70% of the world’s platinum production coming from the area, up to now the city has bounced back with the ebb and flow of mine activities.

But the scale of this latest turbulence has left many bracing for tough times ahead.

Last year’s stoppages squeezed global production by 13%, the lowest in 12 years, according to London-based precious metals firm Johnson Matthey.

Stalled production cost South Africa as a whole $1.15 billion, but in Rustenburg it hit contractors — who provide jobs to at least 30,000 people — particularly hard.

Last year already engineering and construction firm Murray & Roberts ended contracts with nearby Aquarius Platinum and Lonmin.

As ever-increasing running costs and labour turmoil make investors wary of South Africa, fears exist that Rustenburg might collapse with its mines, as happened to other “ghost towns”.

Three hundred kilometers (186 miles) away there is a warning of what could happen.

Welkom — optimistically named “welcome” in the Afrikaans language — once produced a quarter of the world’s gold and employed around 170,000 people in mining.

But its heyday has long gone. The waning industry today employs 30,000 people, while battling with high costs and low gold content.

To prevent a similar demise, Rustenburg’s Chamber of Commerce wants the city economy to adapt so it will survive mining’s eventual decline.

“We have to be more concerned about what to do 30 years from now,” said Malan.

“How do we become less dependent on the mining industry — that’s the important question.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.