SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Can a country just move on from decades of dictatorship and forgive and forget a painful past?

It’s a question Win Tin, Myanmar’s pro-democracy campaigner, raised in the months leading to his death on Monday, April 21, at the age of 84. A strong and sometimes lonely voice against Myanmar’s generals-turned-politicians, Win Tin could well have been talking about the Philippines and other fledgling democracies.

Widely respected as a journalist and his country’s longest-serving political prisoner, Win Tin was a partymate and longtime mentor of Nobel peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi. Together, they founded Myanmar’s pro-democracy party, the National League for Democracy (NLD).

Ever the journalist, Win Tin was critical of the former junta’s democratic transition after 5 decades of military rule. He even called out The Lady, whose transformation from a revered democracy icon to a pragmatic politician disappointed some supporters.

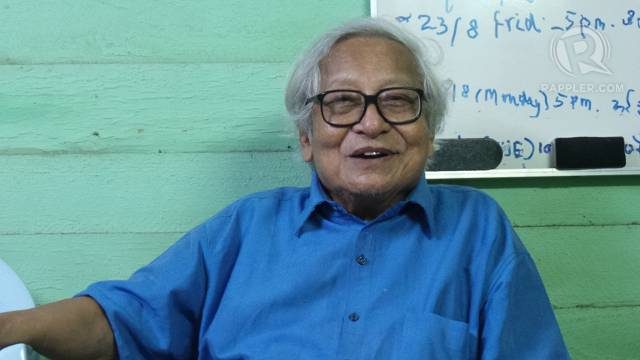

In August 2013, Rappler sat down with Win Tin in his Yangon home to ask him about the dizzying changes in his country. Despite decades of torture and isolation in prison, Win Tin retained his journalistic wit and intellectual vigor. He wore his trademark blue prison shirt, a symbol of his call for the release of all political prisoners.

He talked about the inadequacy of reforms in Myanmar, the changing media environment, and the difficulties of reconciling with the military – themes all too familiar with Philippine history.

Here are excerpts from that interview:

Q: You said that even after the military dictatorship, Myanmar is still in chains. Why?

We had difficult times in 1988 because of the popular uprising and during that time, many people were killed and sent to prison. Many people were forced to leave. The government is trying to mend its ways or try to put some transformation in politics, economy, the social sphere and so on. So all of a sudden, there’s some sort of change.

That is the impression of the world: to embrace the changes in Burma, especially there is some effort to move away from [China’s influence] and move to democracy. Many people put great hope on the new changes.

But on our part, up to now, there is no real change at all. It’s not real. It’s symbolic and very superficial and the worst thing is although they try change, at the back, they always put a sort of string. We are the people who suffered a lot during the military rule and so we want more change. That is our attitude and thinking.

Q: Would you say the same of reforms in the media?

I think that too is in the same category. After this long period of censorship for nearly 50 years, all of a sudden they lift censorship. The journalists themselves are not prepared for the situation. They have their own intimidation, own concerns, own worries. Although they lifted censorship, they are not sure because there is military intelligence everywhere.

Journalists can report and they will follow up and find out your intention. Among the people there’s self-censorship still so they are not free. They report only a meeting is held in such and such, a very short one. So you will find that in the press, there are some articles written by some journalists, writers, politicians but opinion and editorials are very limited so they write travelogue, books, agriculture, dialogue, travelogue, not opinion. Up to now, our expression is very limited. People are not ready to express.

There are some changes in media law. What we propose is if there is to be law, all these laws are to promote and protect, not to suppress, the media. If you want to have freedom of the press, you have to promote it. But if you won’t promote and protect, there will be many restrictions and the press will never develop. If they will not develop, the activities will be very limited and they cannot connect with the people.

Q: Political observers express concern about the pro-democracy party’s aging leaders. How do you intend to develop young blood?

I remember the remark of some of my own colleagues that it seems we cannot cut the umbilical cord of the party. The leaders are over 50 years old. Some of them grandfathers! There is a problem. We are trying to have a youth conference. I hope we will bring out a new generation of young men politically trained. We also have to train our party members about the media. Now they are limited but very soon, they will use the Internet so it will be helpful to enlighten our party members with media training.

Q: You have differed with Aung San Suu Kyi about the reforms in Myanmar. How do you view her stand?

I was a dissident journalist. I was working in journalism since I was a teenager, while I was in university. I worked for a journal, for Agence France-Presse. I worked sometime in Europe, in Holland and Germany. So this is the only profession I understand and worked for in a long time. But Daw Suu has always been a politician because her father [national hero General Aung San] was a politician and she was brought up with military [members] in her family. So we are quite different.

We have differences in the policy or attitude towards the military: how we will regard them, the present [military-backed] Union Solidarity and Development Party, and how we regard our present situation like federalism.

Say for instance about the military, when she came back to Burma in 1988, at that she made a public speech and in it she said that the military is a disciplined organization so people will have to relate with them and work with them.

But for me, sometimes I don’t get that kind of idea. Not that we have a hostile attitude toward the military but to achieve national reconciliation, you can’t just forget. After a long time, you can forget but sometimes, you cannot forgive all the time. Sometimes, it is not easy to forgive the other side like the military.

Q: What will it take to achieve national reconciliation and genuine reforms?

The military has to apologize or they have to amend themselves like, say for instance, set up something like a Truth Commission like in South Africa. Even then, you see, sometimes it will take a long time to forget. The military should know that they have committed some very cruel crimes in the past. They have to review themselves and listen to how people react and how people want for them to amend.

But up to now, the generals who held high positions are still powerful and still pull the strings behind all this. One of them, Khin Nyunt, the former secretary and former prime minister, came out and said that he’s clean of all these crimes, that he just had to follow the order but he killed thousands of people and sent others to jail.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is a very kind person, intelligent person and she’s quite ready to accept their explanations but sometimes, I can’t. Up to now, people don’t forget. That’s why we have to change the Constitution because they (military) cannot be charged.

Q: Another reason for changing the Constitution is to allow Aung San Suu Kyi to run for president. Where do you see her in Myanmar’s future?

We have diverse opinions but there is no split at all. It’s clear that she’s the only leader. In Burma, she’s the only person who’s capable of having the confidence and trust of the people up to now. She’s the only one but there’s a belief that she’s too old. She’s 68. Maybe she can run for another 5 or 10 years. She will be 70 or 75. That’s too much.

It’s very hard [to change the Constitution] but our trust in her – of the party, of the people themselves, even some sector of the military, some sector of the industry –is there. She sacrificed everything about her life for the country. – Rappler.com

This interview was conducted under the Southeast Asian Press Alliance Annual Journalism Fellowship (SAF) Program 2013. Rappler multimedia reporter Ayee Macaraig was one of the 6 fellows of the program.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.