SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MALANG, Indonesia – Beyond the rivers of Sukopuro, in a house built of bricks and stones, a marriage was falling apart. Mina’s husband of 12 years was off to find a new wife — a woman whose womb could continue a lineage, unlike her.

One morning, in an attempt to distract herself from reality, she walked to a nearby library and leafed through the pages of a book she plucked from a shelf. She wiped her wet cheeks, drenched in tears.

“Mbak Mina,” the librarian asked, “Why do you weep?”

“My husband is filing a divorce.”

The year was 2003 in Indonesia. Eko, a librarian in a small village on the eastern part of Java, asked himself: How can I help a woman who faces divorce for a childless marriage?

His phone rang.

The woman speaking on the other line said she was giving out her back issues of women’s magazine, Femina.

“There’s 400 of them at home,” the woman said. “Please take them.” She said she was leaving for Surabaya, and the magazines had to go — to someone else’s hands, or to the junk.

He looked at Mina, and told her to wait. “Someone wants to donate Femina, your favorite read,” he told her.

He hopped on his motorcycle, and off he went. The woman on the phone lived in Malang City, some 15 kilometres away from Sukopuro, a village in Jabung in the regency of Malang, in between fields of sugar canes and rice paddies.

A couple of hours later, he returned to the library. He showed Mina the magazines that came in a sack. He left a second time to take the remaining loot elsewhere.

He would never see Mina again. On his table, she left a note.

Eko,

I am borrowing four copies of Femina. If my plan to fly to Hong Kong to work as a domestic pushes through, I will have my neighbor return these on my behalf.

Mina

It was one of those days where he wished there were more things he could do, like cast spells on a barren womb, so women didn’t have to live feeling at fault for a marriage that failed.

“But who am I?” he asked himself. “I’m just a librarian.”

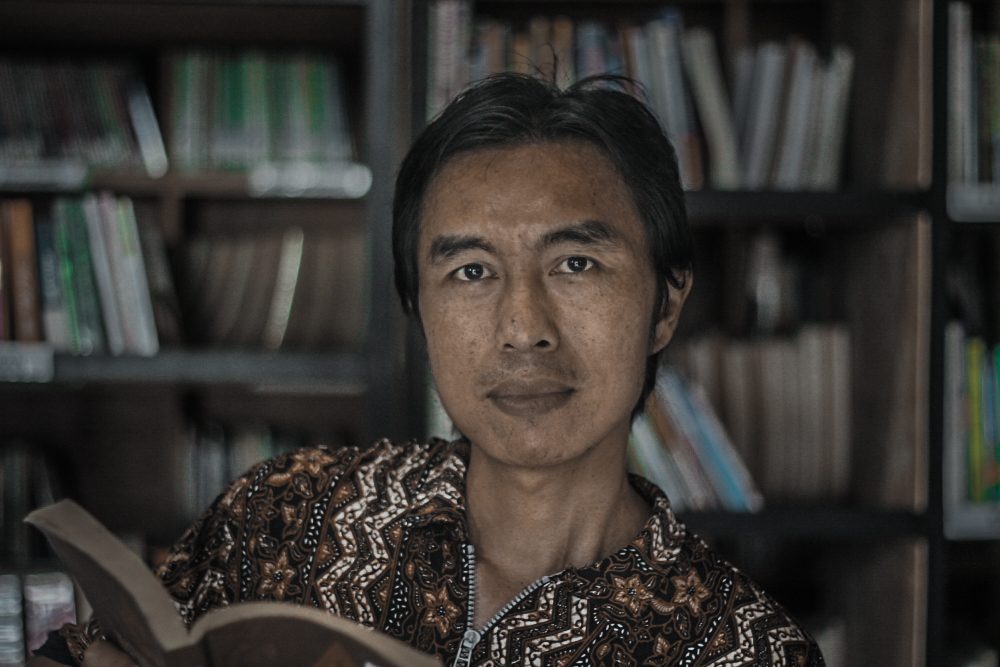

His name is Eko Cahyono. To many he is called Mas Eko, a Javanese term of respect towards older men. But still others call him an attention seeker, a freak who’s life revolves around piles of papers. To some, he is a curator of lewd literature.

“At the village, people don’t have much to do but sit idly and chat,” he told Rappler.

It is that culture that he wishes to break.

THE DAYS of 1998 meander. The leather factory where Eko worked shut down in the wake of a financial crisis. And then jobs became hard to find. To relieve himself from a tormenting repetitive cycle of days, he read everything he could find at home.

One day at the village, he met an old man scanning through the words printed on a newspaper, upside down. It was in that moment he felt a fire in his belly.

Their house soon transformed into a public space. At their terrace, he would hang magazines and tabloids on a clothesline. At night when people weren’t reading, they sang. Sometimes, there would be discussions about public matters.

In his family’s house, a library was born.

On some days he would knock on doors. And when a door opened, he smiled. “Would you like to donate books?” He brought these back to the library so the people would have new things to read.

“I want to promote a reading habit in my community,” he said.

Soon, the library could no longer hold the multitude of books. His parents asked their son, Eko, to move somewhere else.

Eko moved more than 10 times, until finally a neighbor offered a perfect deal: an empty land beside a peaceful graveyard – for rent.

In 2008, he built a library from bamboo and asbestos. He named it Perpustakaan Anak Bangsa, the library of the nation’s children. At the entrance, a pole stood with a flag on top, the emblem of their land.

Children came and read, and he took care of the rest. For a time, together with his sisters, they sold coffee, cigarettes, and gorengan or fried snacks to pay for electricity.

Later, his sisters started their own families, and he was all on his own. He wrote stories and sold them to newspapers. He manned book fairs. He earned commissions from loan referrals. He did all sorts of jobs to pay the rent. And when they weren’t enough, he sold what he had: his television and a motorycle.

One stormy night, a tree fell and violently crashed the library’s roof. The next morning, he knew something had to be sold again.

Perhaps, he thought, “I could sell one of my kidneys.”

NOBODY IN THE VILLAGE, not even his parents, thought of the idea that an erstwhile factory worker and a high school graduate would become a librarian.

Those who frequently visited loved him dearly. But others belittled him and talked behind his back.

Once, police came after they caught wind that he was harboring pornography at the library, even if they were just magazines that discussed sexuality and reproductive health, like a pile of Femina magazine – a favorite among housewives who felt empowered by reading it.

So the police came and left with no evidence. Instead, they ended up borrowing books.

But the library became more than just a building holding books. Readers soon came for company, even advice. One such reader came to ask, “How does a 12-year-old student cope with life when the head of his family, the one who’s supporting them, is only given 6 months to live?”

This was the story of Tema, who a few years ago ran to Eko for advice. He was contemplating quitting school — even if he was only months away from graduation. His father’s diabetes had affected his nervous system. An operation had to be performed, on top of expensive medications. Someone had to pay the bills, and at that young age, Tema felt it had to be him.

“If only I were a man of supernatural powers,” Eko said in a thick Javanese accent. What can a librarian do?

He tucked books inside Tema’s bag. The books were about reflexology, another about ancestral heritage, and still another on traditional medicine. 7 months later, Tema returned, wearing a high school uniform. The books that he lent Tema that gave his father a new lease of life.

Beyond the rivers of Sukopuro is a library—but it’s evidently more than that.

JULY 2017. A FEW DAYS AFTER THE HOLIDAYS, a 16-year-old santri walked into the library.

He grabbed Eko’s right hand. Gently, he pressed it onto his forehead. He asked whether it was alright to come in.

“It’s fine,” Eko told him. He dashed to the comics section, and Eko returned to his table.

“That’s Arif. He stays at a pesantren nearby,” Eko said. “So when he’s free, he comes here to take a break from school-related readings.”

Some 15 minutes later, the boy, clad in an apple green sweatshirt, was silent as he nestled behind a towering bookshelf. The book had transported him into another world.

It was in 2011 when the library was finally reconstructed into a concrete hall, through the help of donors. On its wall, there are picture frames, medals, and trophies, which chronicle the history of a library with a whopping 8,000 membership.

They are students, factory workers, teachers, and household wives who have come here to read from a collection classified by the librarian: wow memukau (awakening), petunjuk hidup (guide to life), superpower, khusus kutu buku (exclusive for bookworms), super hot, and kontroversi (controversies), among others.

Yet despite the concrete walls, a tarpaulin is still the only separation between the library and the outside world.

The books, tens of thousands of them stored inside a tiny 72-square-meter space, are left unguarded – as it’s meant to be, said Eko. So people can come and borrow whatever they want, whenever they want.

Unlike many libraries, the only rule here is to read.

When a UNESCO study revealed that in Indonesia, only 1 out of 1,000 people read a book per year, he was one of those who raised an eyebrow: Who says Indonesians don’t read?

“At the library about 50 people come here every day,” he said.

The problem, he said, isn’t lack of interest to read, but lack of access to reading.

“Indonesians like to read, if they’re given convenient access to libraries. They read, if libraries allow them to read any time of the day, without the usual bureaucracy of requiring them to photocopy their national ID, pay administration fees, and fine them when they couldn’t return the book in a week,” he said.

The books have always found their way back. “I’d like to think that the books are just out there travelling with their readers,” he once told TV Host Andy Noya .

Among those on the “travel” list was Laskar Pelangi, a fictional story of young students on Belitung island in Sumatra, where the kids and their teachers struggle to keep a lone elementary school in the village running, a familiar story not that different from the library’s.

The book was away for a good 3 years beginning in 2006, passing from one hand to another. So in 2008, Noya pledged to give the library 25 copies of it, another 25 of Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code, and dictionaries.

The donation was a moment well chronicled in pictures that hang on the wall. Another frame has a picture of Eko with President Joko Widodo taken at the Palace in April 2017.

The president had invited community librarians around the country to discuss what their needs are. On that day, Jokowi promised to ship 10,000 copies of books to each of them. To make it easy for those who support community libraries, the president also asked state-owned Pos Indonesia to make shipping free for those who send books to libraries every 17th of the month.

Eko has devoted some good 20 years of his life to this noble cause. He said to ensure people have something to read, is a responsibility. His responsibility.

What motivates him to do all these? Now 37 years old, Eko evaded the question, and instead returned to the stories that build the library.

ONE MORNING IN 2007, while attending to the scores of books that gathered dust and webs, a white Toyota Innova parked in front of his house a few steps away from the library. He ran out to find out who it was. A woman in high-heels stepped out of the vehicle.

She asked him where the library was. She must be a donor, he thought.

“How are you, Mas Eko?” the woman in a beige dress and crimson red skirt asked. She removed her sunglasses.

“It’s me, Mina.”

Over the years, Eko often wondered how her life had been. Did the divorce push through? How was her life in Hong Kong?

“Do you remember those magazines I borrowed, Mas Eko?,” she asked. She read them all. The magazines taught her how to improve her fertility.

Those magazines that once became a piece of controversy, that jeopardized a library — saved a marriage. Her husband retracted a divorce petition on the day Mina’s doctor found life in her womb. She gave birth to twins.

At that moment, Eko realized there was no need for him to possess super powers. To be a librarian—it was more than enough to transform lives. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.