SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Less than 60 days before the May 2016 elections, the Commission on Elections (Comelec) has its hands full in ensuring that the country’s 3rd automated polls will go smoothly.

Ballot-printing is underway, vote-counting machines (VCM) are being prepared, two more presidential debates are on deck, and voters’ information campaigns are ongoing.

Then on Tuesday, March 8, the Comelec hit a major snag: the Supreme Court (SC) issued a ruling that requires the poll body to print voter receipts on election day, a feature that would require a fresh round of bidding and which some quarters say may require touching the source code for the vote-counting machines.

This further placed the poll body into “panic mode,” prompting it to hold an “all-hands emergency meeting” the following day.

Amid all these developments, might the Comelec still be missing something? Are there measures the poll body can still adopt to boost confidence in the election results and minimize potential allegations of cheating?

Through insights derived from the 2010 and 2013 unofficial election results data as well as from interviews with election watchdogs and IT experts, Rappler came up with 7 action points for the Comelec that are still doable in time for the 2016 automated elections.

Click on each item to read more about the action point.

1. Activate the Voter Verified Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT)

The VVPAT is essentially a receipt that the counting machines would print after a voter feeds his or her ballot into it. The receipt is then deposited in a separate ballot box.

The feature allows voters to verify if the machine correctly read his or her votes. “If there is a mismatch, the voter can raise the issue with the BEI (board of election inspectors) so it is recorded in the minutes,” said Lito Averia, an IT consultant for the National Citizens’ Movement for Free Elections (Namfrel).

Not all the watchdogs are keen on this feature. Averia himself concedes that the downside of this feature, which the Comelec raised in the SC case, is that in doing so, the voter raising these issues will waive their right to privacy. It can also potentially be used for vote-buying, as it becomes proof of how a voter voted. (Read: Why it’s alright not to have voting receipts)

But not providing the VVPAT, according to Averia, is a violation of the voter’s right to know whether the machine has accurately registered his or her votes. “I don’t see how the machine scans my ballot. I don’t see how the machine puts together the election results. I never saw the count.”

Disabling the voting receipts feature is also against the Automated Election System Law, or Republic Act 9369, argued former senator Richard Gordon, who filed a petition before the SC regarding the VVPAT.

The SC on March 8 unanimously ruled in favor of Gordon, and required the Comelec to issue voting receipts for the May 9 national and local polls.

In a press conference held after the SC released its decision, the Comelec said turning on the feature could affect the overseas absentee voting (OAV), and might derail the timeline for the polls itself. (READ: Comelec mulls postponing polls amid emergency)

In this situation, Averia said a possible compromise could be reached where, if the OAV voting is affected, the VVPAT will not apply to the OAV.

Asked if software changes are needed to activate VVPAT on the voting machines, Jimenez told Rappler through a text message that no software changes are necessary. “It’s part of the configuration package kasi. So basically, on or off lang. But the problem is doing that for more than 90,000 machines.”

On February 13, the Comelec conducted mock elections in 40 areas in 9 provinces and Metro Manila. This is to test the automated election system (AES) software and the transmission of election results (ER).

But according to lawyer Rona Caritos of the Legal Network for Truthful Elections (Lente), the mock polls used a fast broadband global area network (BGAN) satellite connection. “Of course those will transmit successfully,” Caritos said, adding that BGAN units are expensive.

However, this won’t be the normal scenario on election day. Like in 2010 and 2013, most of the VCMs will use SIM cards and will transmit through mobile data networks. The BGAN devices will only be used as a back-up transmission method.

Caritos hopes that the Comelec would hold another mock election, but with the VCMs transmitting via mobile data networks. She also suggested that this takes place ahead of the final testing and sealing (FTS) procedures for the machines, which are done at least 3 days before election day.

The February mock polls included only 4 of the 40 voting centers with low transmission rates in past elections. Caritos said the next mock elections should be held in more areas where the VCMs failed to transmit to the transparency server in 2010 and 2013. This is to test if transmission issues that affected previous elections have been addressed. Our PCOS transmission status map for the 2013 elections show which areas had problems transmitting to the Transparency Server.

Below is a table of the transmission rates during the 2013 elections at the 40 voting centers that hosted mock elections in February 2016:

Comelec’s Jimenez confirmed to Rappler that BGAN (satellite Internet connection) was used during the February mock polls, adding that the SIM cards “weren’t ready” yet at the time.

He also said that there will be a second nationwide mock election in April, with the results sent using the SIMs.

Jimenez added that BGAN units will still be deployed on May 9 to handle instances when transmission fails via mobile networks.

3. Make sure the Transparency Server gets all the results

On election day, the VCMs transmit copies of the ERs to 3 servers.

The first transmission goes to the city/municipal canvass server. This transmission is considered the official results, used as basis for the proclamation of winners at every administrative level.

The second transmission goes to the Comelec central server in Manila. (READ: How does the PH automated election system work?)

The third transmission goes to the Transparency Server, which shares the results with watchdogs and media groups. In 2013, the Rappler Mirror Server connected to the Transparency Server in order to electronically tabulate the election results in real time. (Read: Rappler mirror server: Real-time results for TV stations, Namfrel)

Results canvassed via the Transparency Server are considered unofficial. Watchdog groups say, however, that it is still a critical part of the process.

In 2013, Rappler analyzed the election results from the Rappler Mirror Server, which received data via the Transparency Server, and came up with a number of insights from the data. These included:

- Votes from certain precincts were unaccounted for 2 days after election day. The number of votes involved was critical as it could still affect who gets remaining seats in the Senate. (READ: Where are the 11.9 million votes?)

- There were links between special election operations on the ground and the data received, such as the fact that 5,300 PCOS machines transmitted data at dawn days after polls.

- There were precincts with 100% turnout rates, which is indicative of cheating.

By analyzing this stream of data, Rappler also dispelled rumors of a 60-30-10 cheating pattern in the results, highlighting the role that the law of large numbers plays in the equation.

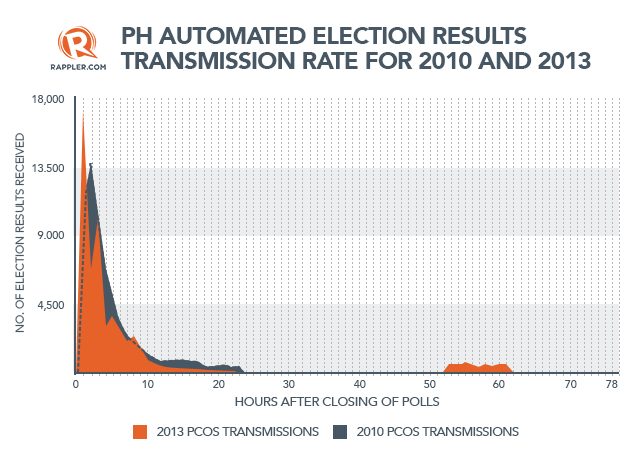

The Comelec, however, has not put enough thought on the role the Transparency Server plays in building credibility for poll results, observers say. In fact, compared to the first automated elections in 2010, the number of election results received by this server in the 2013 elections decreased dramatically.

In 2010, the Transparency Server received 92% of ERs. In 2013, it received only 76% of ERs.

Rappler’s real-time PCOS Transmission Status map for the 2013 elections shows that the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), considered a hotbed of cheating in previous elections, transmitted less than 40% of results to the Transparency Server. Of the ARMM provinces, Lanao del Sur was least successful in transmitting results in 2013. Less than 20% of results from the province made it to the Transparency Server in 2013.

Outside of the ARMM, an area of concern was Taguig City in Metro Manila, because it transmitted less than 50% of results.

“The Comelec should have learned its lesson in 2010 and 2013; the transparency server should be given more importance,” Caritos said.

She adds: “If I were the Comelec, [I will] treat the Transparency Server with the same importance as the official results. Critics will always use the Transparency Server results as evidence of flaws in the process.”

4. Make data transmitted to the Transparency Server more auditable

The Comelec should also make the system more auditable by allowing parties connecting to the Transparency Server to get copies of the actual electronic version of the election returns, according to Averia, who was also a participant in local source code reviews of the various AES software.

In the 2010 and 2013 elections, observers who connected to the Transparency Server, including Rappler, received the results in CSV (comma separated value) format. Each row on the file represented results from one machine.

The problem with this, according to Averia, is that this does not show natural audit trails for checking veracity of the transmission. “Each machine sends a file in EML (Election Markup Language) format. This is encrypted and transmitted,” Averia explained.

He said the public key for decrypting those files should also be given to parties to the Transparency Server for them to use to decrypt. “Providing the decryption key is another transparency measure.”

For audit purposes, Averia said, the EML copy received by the Transparency Server can then be compared with the EMLs transmitted to the consolidation canvassing system (CCS) at the level of the municipal and city board of canvassers.

It can also be compared with the copy at the Comelec Central Server. “It should be possible to crossmatch. Anybody who wants to change results will have to change all 3.”

Averia also adds that appropriate metadata should also be provided so that it is possible to see the source of transmission and account for each machine. “In 2010 and 2013, we were only able to account for the PCOS IDs.”

While the Comelec assigns one voting machine per precinct, theoretically, a single machine could send results from multiple precincts. The general instructions to election officers allow this in case some machines fail to transmit.

Actions of election officers are supposedly logged in the minutes for each precinct. If Averia’s suggestion is followed, observers should be able to check which machine sent multiple results, and independently verify such transmissions on the ground. It should also be possible to check for rogue or renegade machines transmitting results.

In the past two automated elections, the Comelec did not allow access to the EMLs and the public decryption keys for security reasons. Averia points out, however, that public keys are a feature of digital signing.

“This is not a security issue because that is the feature of digital signing.” In digital signatures, he explained, there is really the concept of public and private key. “The public key is a way to check integrity [of the data]. These are the imprints of the machines.”

5. Avoid further delays; the AES should be all-systems-go at least a week before the polls

With reports on delays in the printing of 57 million ballots and on the rebuilding of software source codes, Lente’s concerns on the readiness of the AES grew. “Kapag may delay, nagmamadali lahat, mas prone siya to mistakes,” said Caritos. (When there’s delay, everybody’s rushing, making things more prone to mistakes.)

These hiccups may rear its ugly head on election day. That’s why the final testing and sealing (FTS) of the vote-counting machines at least 3 days before the polls is important: it aims to catch and address untoward incidents in the voting process.

But with the delays in other aspects of the election system, the FTS may be in danger of being pushed back as well. Caritos explained, “As much as possible, we want [the FTS] to happen a week before election day, so if ever issues or problems would arise, there’s still sufficient time to remedy that.”

6. Make Smartmatic accountable for delays, mistakes

Both Caritos and Averia said that software provider Smartmatic should have anticipated the delays in testing and preparations, and should have been more prepared in dealing with it. Smartmatic also provided the Comelec with the AES in the last two automated elections.

For example, Caritos said that Smartmatic should have been aware of the issues on the source code, specifically the reported “incompatibility” of two source codes.

Caritos believes, “Masyadong bine-baby [ng Comelec] ‘yung Smartmatic eh.” (Comelec is going soft on Smartmatic.) Comelec Chairman Andres Bautista even enlisted the help of the media and the public to pin down the Venezuela-based technology firm.

Averia added that the Comelec should revisit the contracts it had signed with Smartmatic for possible fines. “My answer: [look at their] specific performance…. Did they deliver or not? Go back to the contract,” he said.

There should be penalties for performance issues, according to Averia. He also noted that if those penalties are not on the contract, “they may be other laws that may be used to determine the prescription of fines.”

7. Gear up for unexpected election day incidents

While the elections have gone generally peaceful and orderly in recent years, the threat of election-related violence and further unforeseen incidents in the polling places still loom.

There is also the possibility of teachers refusing to serve in the board of election inspectors (BEIs), notably in “areas of concern” and the ARMM, which has a history of cheating and election-related violence.

While they are required by law and they remain eager to serve as BEIs, public school teachers may still worry about their safety and decide to back out, especially when incidents suddenly flare up in those communities.

Caritos noted that there are backup poll workers – such as police personnel and individuals of known probity and competence – when such incidents take place. But it would delay the opening of the polls in those affected areas.

“When there are delays in the vote, people will be more agitated, more stressed. They might think, ‘Hey, there’s cheating going on because we cannot vote yet.’ That may spark or contribute to possible incidents. We don’t want that to happen.”

Water under the bridge

The action points above will not totally guarantee that no cheating will happen, watchdogs say. Unfortunately, other courses of action – such as ensuring a proper code review process – are already “water under the bridge,” Averia admits.

“This should have been done before the software was installed on everything. Since ginagamit na, tapos na ang laban. Pangpalubag-loob na lang ang review ngayon.” (Since the software is already being used, the fight is over. The code review process is now just a matter of consolation) – with Wayne Manuel/Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.