SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

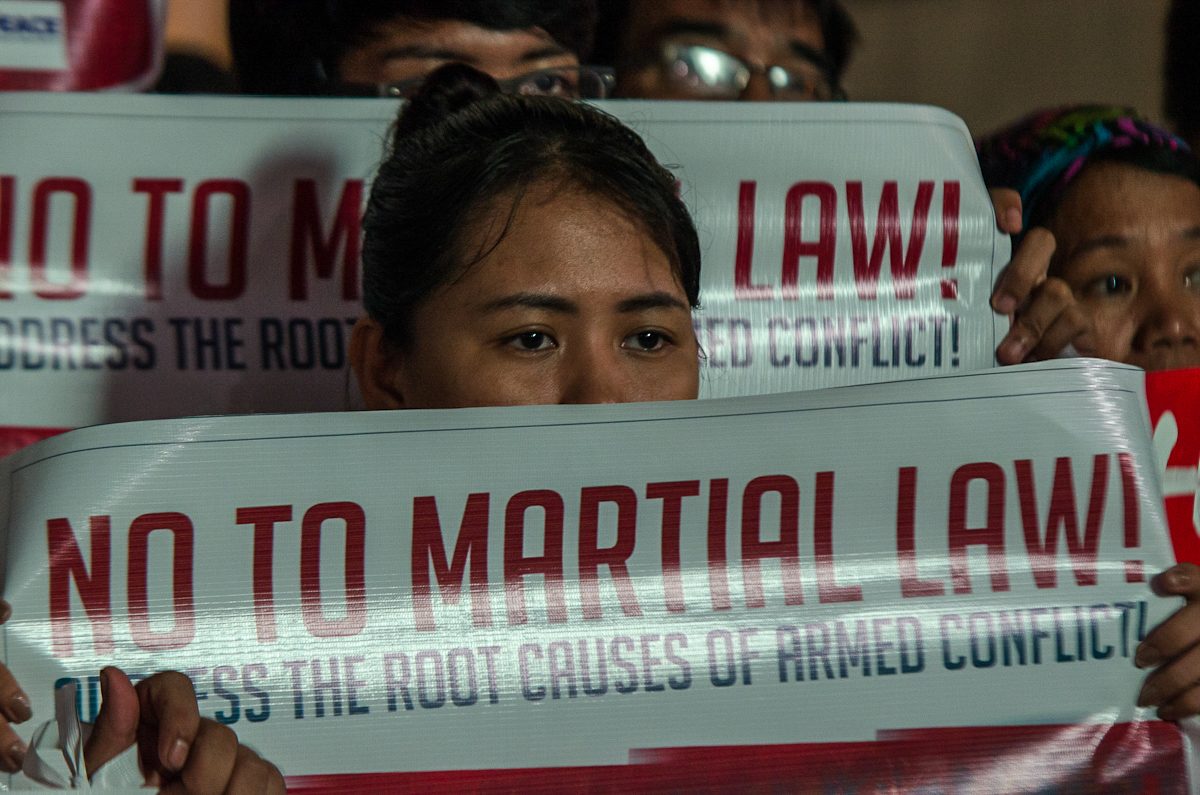

MANILA, Philippines – President Rodrigo Duterte made good on a year’s worth of pronouncements when on Tuesday, May 23, he used his constitutional power as commander in chief and declared martial law in the entire island of Mindanao.

It followed the crisis in Marawi City when the military launched a strike against targets from ISIS sympathizers and terror group Maute Tuesday afternoon.

The military offensive set off a chain of violence when Maute members launched their own attacks that continue until Thursday, May 25. (READ: Duterte confirms Maute terror group’s ISIS links)

Here are questions you need to ask to know about this localized coverage of martial law:

1. Was it justified?

There are two grounds for the President to declare martial law.

Section 18, Article VII of the 1987 Constitution states: “In case of invasion or rebellion, when the public safety requires it, he may, for a period not exceeding sixty days, suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus or place the Philippines or any part thereof under martial law.”

Christian Monsod, one of the framers of the 1987 Constitution, had said in various media interviews that the situation in Marawi City does not qualify as rebellion.

“It doesn’t look as if it’s a rebellion under Section 134 of the Revised Penal Code. The President certainly can call the armed forces to suppress or prevent lawless violence, this sounds like lawless violence to me, not rebellion,” Monsod said in an interview on GMA News TV’s News To Go on Wednesday.

Section 134 defines rebellion as “a crime committed by rising publicly and taking arms against the Government for the purpose of removing from the allegiance to said Government or its laws, the territory of the Philippine Islands or any part thereof, of any body of land, naval or other armed forces, depriving the Chief Executive or the Legislature, wholly or partially, of any of their powers or prerogatives.”

“From what I hear, Marawi is still under the control of the local government and the military is well-positioned there to address any kind of violence and terrorism,” Monsod said. (READ: Martial Law 101: Things you should know)

2. Why the whole Mindanao?

Lawyer and political analyst Tony La Viña said there is basis to declare martial law but only in Marawi City where the local executives can no longer function.

“In Marawi, I think it is necessary to give the military the control over the city but why would you do it, say, in Cagayan de Oro, when it’s not necessary?” La Viña told Rappler in a telephone interview.

The danger here, according to La Viña, is that it opens the possibility of a military officer taking control of other provinces in Mindanao which are not facing the same threats to public safety as Marawi. When that happens, a military officer will be entrusted with the responsibility to run a city, its politics, its businesses and its day-to-day operations with constituents despite the lack of qualifications for it.

Duterte had also categorically announced the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, which, in essence, means the state, subject to restrictions specified in the Constitution, can arrest anyone without warrant and jail anyone without trial in Mindanao.

While the suspension of the privilege of the writ may help the military catch rebels in Marawi City, La Viña questions whether the same is necessary for other provinces in Mindanao.

For La Viña, martial law is only necessary when the civilian authorities can no longer govern. It may be the case for Marawi City, La Viña said, but it’s definitely not the case in other Mindanao provinces where their local governments are fully-functioning.

3. What happens to local governments?

The 1987 Constitution, crafted in the aftermath of the almost 10-year Martial Law rule under the late former president Ferdinand Marcos, made sure that the president’s powers were limited.

“There’s still the bill of rights, the civilian courts, it says you cannot abolish Congress. But the most worrisome is that the law is silent on the role of local executives,” La Viña said.

When then president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo declared martial law in Maguindanao in December 2009 after the massacre that killed 58 individuals, there were reports that an army officer would take on the role of governor to replace Andal Ampatuan Sr.

This was necessary, according to La Viña, because Maguindanao’s leaders, including the governor, were suspects in the massacre, if not, related to the suspects.

But what happens in this context?

Political Science professor Arjan Aguirre of Ateneo said local chief executives – barangay captains, mayors, and governors – would have to yield majority of their powers to the national government.

4. What can and can’t the army do?

Lawyer Darwin Angeles told Rappler that a warrantless arrest is only valid if 3 criteria are met:

- When you have committed, are actually committing, or are attempting to commit an offense in the presence of the arresting officer;

- When an offense has just been committed and the arresting officer has probable cause to believe, based on personal knowledge of facts and circumstances, that you committed the offense;

- When you have escaped from prison or detention or while being transferred from one confinement to another;

The Department of National Defense (DND) has already issued a reminder for the military that “any arrest, search, and seizure executed or implemented in the area or place where martial law is effective, including the filing of charges, should comply with the Revised Rules of Court and applicable jurisprudence.”

This is because even though the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus is supended, the 1987 Constitution, learning from the Marcos era, made sure that the bill of rights remains in place.

An army officer can arrest and detain a person without court order on the grounds above, but he should make sure that the person is judicially charged within 3 days, otherwise, he or she shall be set free.

It means the suspension is valid only within those 3 days to cope with the urgency of the situation, but due process following court procedures still has to be followed after that.

It is also important to remember, La Viña said, that the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus applies only to crimes and offenses “inherent in or directly connected” to invasion or rebellion.

If the crime you are accused of does not have anything to do with invasion or rebellion, regular procedures follow.

5. What happens to Proclamation 55?

After the bombing in Davao City in September 2016, which was followed by central Manila being put on high alert, Duterte issued Proclamation 55 or a declaration of a state of national emergency on account of lawless violence.

Under the proclamation, Duterte called on the military and the police to “undertake such measures as may be permitted by the Constitution and existing laws to suppress any and all forms of lawless violence in Mindanao and to prevent such lawless violence from spreading and escalating elsewhere in the Philippines with due regard to the fundamental civil and political rights of our citizens.”

Duterte has not lifted Proclamation 55 to this day.

Can they overlap? La Viña said yes.

“Proclamation 55 did not have a legal effect, it was a declaration of a state, it did not create any new power, at most it gave the President the power to designate to the army the duties which ordinarily belong to the police,” La Viña.

He added: “Proclamation 55 is now considered superseded and in fact they can now say that the proclamation did not work before and so they’re declaring martial law now.”

6. Who will have the last say?

One thing’s for sure now, Mindanao is under martial law for at least the next 60 days beginning Tuesday, unless Duterte or the Congress revokes it.

Duterte has first move on everything. He either lifts it before the 60-day period is over or he extends it after that, subject to the approval of Congress.

If Congress revokes it, then it’s over. The Constitution is clear that “such revocation shall not be set aside by the President.”

If Congress decides to extend it, they determine for how long.

While this process is ongoing, any Filipino citizen can run to the Supreme Court (SC) to question the factual basis of the martial law declaration. The SC is mandated by the Constitution to review the declaration on the basis of such petition and issue its decision within 30 days.

“From a legal point of view, SC has the final say,” La Viña said.

Upon arriving home from Russia late Wednesday afternoon, Duterte said he may expand martial law to Luzon and the Visayas if the threat of ISIS persists.

With that looming over the country, it will do us good to start to persistently ask these questions now. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.