SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

I met him along one of the many dusty corridors of the university library.

He was hard to ignore. He was, after all, a Management Engineering graduate, high school valedictorian, a catechist, and a student leader. There was something about Edgar Jopson (Edjop as he’s more popularly known) that enthralled.

Long after my history paper was submitted and graded, I still found myself embracing every sentence, paragraph, and chapter of books about him. (I don’t remember if I did well in that paper or not, or if my paper did justice to his life.)

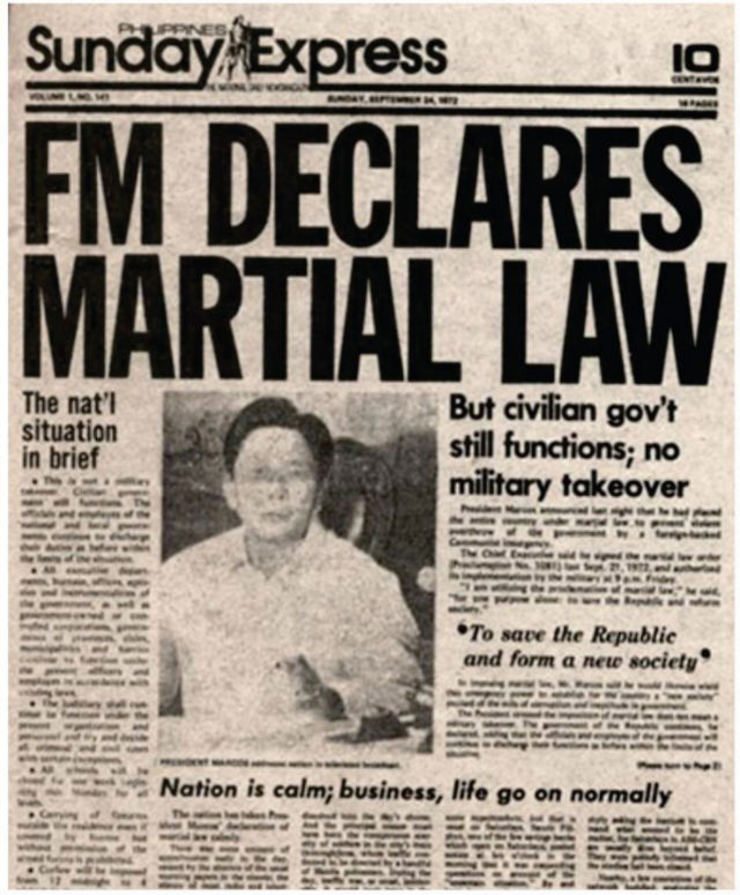

Maybe it was his meeting with the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos, wherein he tried – in vain – to convince him to opt out of a third presidential term. An angry Marcos told Edjop: “Who are you to tell me what to do? You’re only a son of a grocer!”

Or maybe because there was something romantic about a bright-eyed, middle-class Atenean who went from being a moderate to being one of more promising members of the Communist Party of the Philippines.

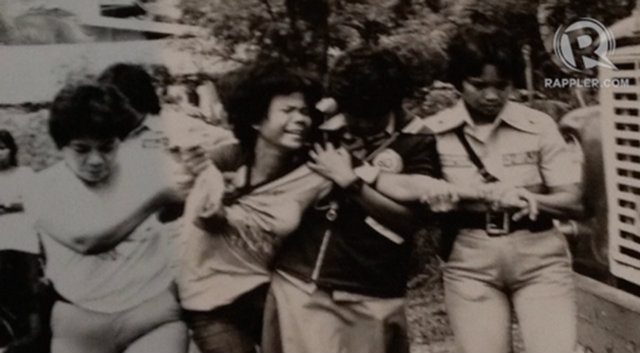

Or maybe because Edjop, living and struggling under the oppressive shadow that was Martial Law, did something I could never have done had I lived in the same era – go underground, and die a martyr, fighting against military rule until his dying breath.

It’s the memory of Edjop, and many people like him, that infuriates me when people scoff at the thought of a “politicized” Ateneo.

And it’s the memory of Edjop that left me at a loss for words when I found out that Imelda Marcos, wife of the former dictator, was a “guest of honor” at an event for scholars of the university.

To be fair, it was probably a moment many people – including and especially those in the room – did not expect to see in their lifetime. The irony – and some would say, lunacy – of Imelda’s presence was not lost on Ateneo alumni and faculty. A photo of Mrs. Marcos posing with several of Ateneo’s recent valedictorians went viral on social media, but was immediately taken down. The photo was something they “are not very proud of,” said one alumnus. It was the understatement of the day.

It was as awkward as awkward could get. Imelda was there because, it turns out, she helped the Ateneo Scholarship Foundation (ASF) – a non-stock, non-profit corporation not under the supervision of the university – way back in the 70s. The revelation made by no less than the Ateneo de Manila University’s president Fr. Jett Villarin, SJ, has opened up even more questions about the source of funds, but that’s another story altogether.

The virality of the photos from the event pushed the university’s public relations arm to issue a statement. “I would like to reaffirm that we have not forgotten the darkness of those years of dictatorship and that we will not compromise on our principles in forming those who would lead this nation,” said Villarin on Sunday, July 6.

“Please know that in the education of our youth, the Ateneo de Manila will never forget the Martial Law years of oppression and injustice presided over by Mr Ferdinand Marcos. We would not be catching up on nation building as we are today, had it not been for all that was destroyed during that terrible time,” he said.

Sorry for what?

At the exact moment someone thought it was okay to invite the former first lady to an event honoring the university’s best and brightest, something was amiss. This was the same woman who stood by Marcos as hundreds of Filipinos disappeared without a trace during Martial Law.

The notion of “nation building” and the university’s promise not to forget “the darkness of those years” felt like nothing more than lip service, especially to the many who fought and continue to fight the good fight.

A lot has been said about the visit, about the university’s subsequent apology, and about the Marcos apologists who populate social media.

In what can only be called a public relations nightmare, the university’s “apology” for the Imelda invite was also met with criticism: Why apologize? Why extend an invitation in the first place? Was Ateneo playing lapdog to the Aquino administration?

“How hypocritical of the school, whose alumni are also as corrupt as the likes of Imelda!” one angry commenter said.

Random commenter X and Y have a point. Maybe it was off-putting to take back the invite by issuing a public apology. I am ambivalent towards the “apology” because I’m not sure who Fr. Villarin and the university were apologizing to or what they’re apologizing about.

Are they saying sorry to the hundreds who made a fuss on social media? To those who’ve been dutiful in picking a #NeverAgain post day by day? To the alumni from that era whose classmates and friends were never heard from again?

Are they sorry for the negative reactions the pictures got? For the lack of foresight (did nobody really expect the backlash the invite would create?!)?

Or are we sorry because her presence speaks of a forgetfulness we deny?

I can be a tad bit idealistic at times, foolish to some, but I hope the sorry was for Edgar Jopson, Emmanuel Lacaba, Evelio Javier, and the rest – sons of the institution that takes pride in its role in “nation building.”

My generation

Still, many do not understand the outrage on social media. What’s the fuss? Why can’t we let bygones be bygones? And who are we, of such young age, to cry foul over the whitewashing of an era we didn’t even live in?

Part of the outrage, I believe, is because of what Imelda’s visit does or did not do to the memory of Ateneo’s Martial Law martyrs. A memory, that to some, is far, far away.

I am part of the generation born after those tumultuous years. I am lucky because brave Filipinos endured torture, lost their lives, left their loves ones so that I would not have to go through the same ordeal. I can’t claim to even understand how difficult the Martial Law years were, or how it felt to be part of the First Quarter Storm.

What I know comes from my history lessons, articles and books written about that dark period in Philippine history, and my late mother’s own account of how she was quickly sent back to Tacloban from UP Diliman because my grandfather was worried for her safety. (My grandfather was convinced that my mother had left-leaning views, a charge my mother vehemently denied.)

Back in college when I was an editor of The GUIDON (Ateneo’s official school paper), we did a story on Ateneo’s “Forgotten freedom fighters.” Today’s students know little of the university’s Martial Law heroes. Lisandro “Leloy” Claudio, who was then a history teacher in the department, said it’s likely because it’s difficult to “sanitize” heroes associated with the CPP, such as Jopson.

Said Claudio: “It saddens me because who we remember and how we remember them has an impact on how our students think. I read someone write on the Ateneo website, ‘the makibaka politics of the ‘70s are now over.’ Aray.”

One of my greatest fears is to forget. I am afraid that one day, I’ll forget what my mother was like.

I am afraid that one day, given the Marcos apologists inundating social media, I’ll be one of many Filipinos afflicted with amnesia – unable to recall what our mothers and fathers and grandmothers and grandfathers told us about Martial Law. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.