SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Spoilers ahead.

In a post-truth age, political art matters more than ever.

Yet not all political art deserves applause. There are those which can stand on their own merits and which align with the values of the communities they draw their stories from — from Esteban Pichay Villanueva’s paintings on The Basi Revolt in 1821 to Jeannette Ifurung and Mike Alcazaren’s film 11,103 in 2022. However, many recent efforts have gotten free passes for being “timely” and “relevant” — buzzwords used by critics (and I admit, I have been one of them) who are too lazy, too busy, too irresponsible, or not well-read enough to come up with something more precise.

It is one of the reasons why poorly made art — ones careless about positioning, politics, process of creation, and modalities — can thrive. Like a microenvironment that supplies tumors with the factors for successful metastasis, an uncritical culture, a community that insists on vagueness and sentiment without fair assessment, enables bad art to be made, encourages similar storytellers to be as reckless and thoughtless, and capitalizes on our tendency to leave things unquestioned. The audience (and I include myself in this) must be empowered to feed their curiosities, to educate themselves, and to challenge not only artists creating the work but the critics that praise and dismiss it (and I am not immune from such criticism).

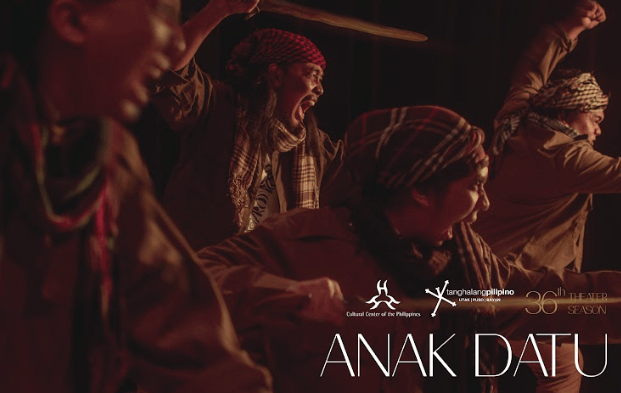

For its 36th theater season, Tanghalang Pilipino has decided to mine our country’s dark history and to challenge the dominant images of heroism. While Virgin Labfest was a mixed bag this year, the company has found success in its first solo offering — Anak Datu. But to merely praise Anak Datu for its relevance and social commentary diminishes the many feats of imagination it manages to pull off, particularly in reflecting the power dynamics that keep those in the Southern Philippines in a chokehold.

Using the short story by National Artist Abdulmari Imao as a foundation, playwright Rody Vera creates a stage adaptation of Anak Datu that expands beyond the source text — adding a gritty socio-realist examination of the roots of insurgency in Mindanao and a fictionalized staging of the tensions within the Imao household during the 1970s. By transforming Anak Datu into a triptych that exists somewhere between fiction and fact, Vera not only demonstrates how art contains fractals of history, but also how social realities shape what stories we tell, how we tell them, and, more importantly, who gets to hear them.

Still, the narrative can get overwhelming. It helps that director Chris Millado employs other artforms to allow the intertext and cultural specificity of Anak Datu to surface. Projections designed by GA Fallarme turn the stage into Imao’s canvas, utilizing images of the sarimanok that have grown characteristic of his work. Set pieces created by Toym Imao, son of the late National Artist, constantly shift along the traverse staging like boats across time and space. When paired with Carlo Villafuerte Pagunaling’s textured costumes, they transform the actors into childhood toys — an effect more chilling when it contrasts the carnage to come. The soundscape — a combined effort of sound designer TJ Ramos, composer Chino Toledo, and the Philippine Women’s University Indayog Gong Ensemble — gives body to every thrilling escapade and every heartbreaking turn. These elements converge and make Anak Datu a sensorial experience that demands to be seen live.

The first act of Anak Datu is defined by the process of myth-making and recollection. It begins with Abdulmari Imao (Marco Viaña) who, along with his Christian wife Grace de Leon (Antonette Go), introduce their son Toym (Carlos Dala, in one of his two roles) to the short story Anak Datu. The staging transports us into a musical folktale detailing the love blossoming between Datu Karim (Hassanain Magarang) and his wife Putli Loling (Lhorvie Nuevo), a relationship cut short when they are ambushed by Jikiran (Earle Figuracion) and his pirates. Forced to give birth in captivity, Putli Loling raises her son Karim (Carlos Dala, in his second role) with Jikiran as a surrogate father.

Vera parallels the birth of Karim with the birth of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) in Mindanao and, subsequently, the awakening of Toym’s social consciousness around the realities of the world.

Anak Datu is at its most affecting and haunting when it dives headfirst into its documentary material, conjuring evocative imagery around two turning points in the armed conflict in Muslim Mindanao. The Jabidah Massacre in 1968, the event that spurred the formation of the MNLF, is told from the perspective of an old Jibin Arula (Nanding Josef), one of the only survivors of the massacre. Arula recounts his teen years as a Tausug trainee (Mark Lorenz) recruited by the Marcos government to incite civil unrest in Sabah in the hopes of regaining control over the region.

Millado and lighting designer Katsch Catoy use light and shadow play to separate the present and the past, confining the teen Jibin and his fellow recruits to a green-tinged memory and the older Jibin to a red-stained future. When their trip to Corregidor ends in bloodshed, Catoy swaps the lighting of the two, bathing the older Jibin in green light as he walks backwards, an artistic decision that physicalizes his entrapment in the past.

The second turning point is a detailed account of the Palimbang/Malisbong Massacre in Sultan Kudarat, told in a manner similar to group counting — an inspired physicalization of community storytelling. Hassanain Magarang turns violence into choreography, his movement design giving shape to the community’s anguish and loss, while Fallarme replaces projections of Imao’s colorful illustrations with the names of the victims of the massacre, forming a black-and-white mosque. It is a bone-chilling moment of silence, one that imprints the audience with what is at stake in this retelling.

The second act shatters the facade of innocent art and introduces the many rampant forms of erasure — from concealment of narratives of violence to censorship in television during the Martial Law era to the differences between silence and forgetting. While Tex Ordonez-de Leon functions in the first act as a conduit for truth and love through her soulful ballads, Millado uses her as the face of a complicit media — weaving in and out of the scene, rapidly firing mistruths with a smile and perfect posture.

Despite these, Anak Datu struggles with its narrative structure. Theater critics Fred Hawson and Arturo Hilado have previously expounded on this sentiment in their earlier reviews, with Hilado confessing to “feeling lost in the early stages of the sung narratives.” The strength and weight of the documentary sections make it difficult for subsequent scenes to be tonally rescued, with moments of levity registering, at times, as inauthentic. In its attempts to arrive at sentiments of peace for the next generation, it cuts many of its important threads loose and absolves complicated generational political issues through motherhood statements.

Such problems are rooted in how underutilized the short story is as a framing device. As already pointed out by BusinessWorld Online’s Michelle Ann Soliman, the lack of a narrative counterpoint is also a missed opportunity. Though there are moments between the elder Imao and his wife Grace de Leon, stronger juxtapositions between the three threads, maybe even allowing the characters themselves to wrestle with the intertext, would have left the audience with a far richer experience. If the play is to be restaged, it is best that its narrative scaffolds be interrogated and reconsidered.

It must be mentioned that Anak Datu exists as an educational piece for those who are not directly affected by the consequences of war — with Millado and Vera functioning almost like the elder Imao and Dala’s Toym being a stand-in for what can only be assumed as a predominantly Luzon-based audience. Many of the critics and reviewers, including myself, who have praised Anak Datu hail primarily from Luzon, and one is left to wonder: Will such a piece resonate in a similar manner if it is staged in Muslim Mindanao? Especially in locations where violence is not merely in the past but in the present, where wartime is not merely hypothetical but reality, where such conflict exists immediately outside the four walls of the theater? Will its messages of peace and persistence amidst conflict and death read as hope, naiveté, or ignorance?

This “exile” of the story has created a peculiar paradox. Can the story exist in its most daring form when it lacks distance or have we, like Jikiran did to a young Karim, simply kidnapped the story and raised it until the conditions were favorable enough for its return?

Only time will tell. – Rappler.com

‘Anak Datu’ runs from September 16 to October 9 at the Tanghalang Ignacio Gimenez, Cultural Center of the Philippines, Pasay City. You may reserve your tickets through Ticketworld.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Political parties must embody Bangsamoro people’s aspirations](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/imho-bangsamoro-embodiment-03212024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.