SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

For educational and political art to be truly effective, it must succeed as art.

But how does one write about, let alone criticize, art that tackles such a sensitive topic as Martial Law? Politically charged material — especially those about and by people from marginalized communities — already struggles to be made and seen. Add that to the fact that most in-person theater productions have been shut down for more than two years now, and any criticism, no matter how thoughtful, may register as distrust or, even worse, dismissal. I have been told time and time again: why kick an industry, or worse an entire community, down when they’re already suffering?

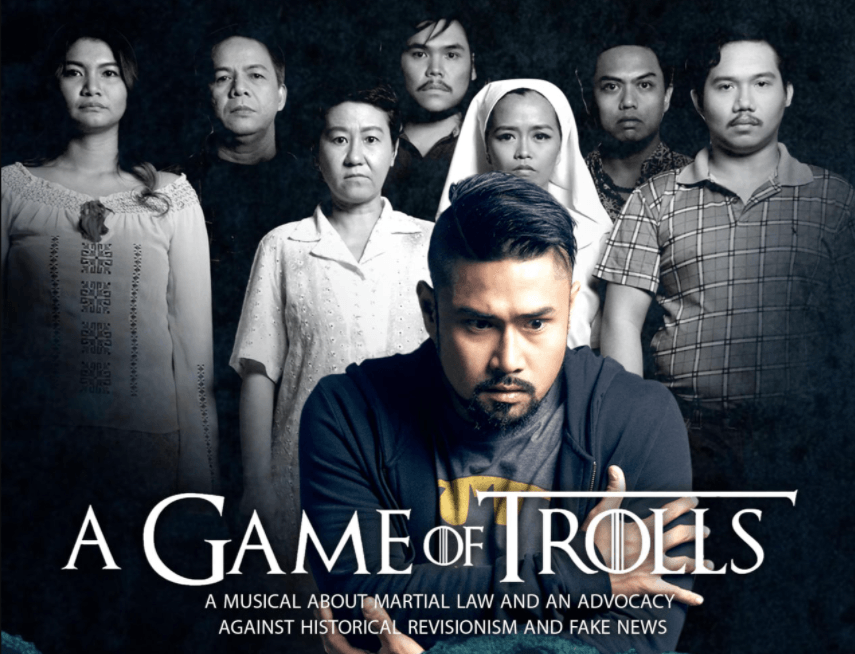

Faced with this ethical predicament after Thursday’s screening of A Game of Trolls, I sifted through online reviews of the 2017 production, hoping to glean some form of insight. Most of the writing centered around the production’s timeliness and advocacy and, for the most part, this praise is earned. A Game of Trolls was created as a part of a countermovement against historical revisionism, the growing culture of impunity, and the machinery of disinformation that has been set in motion, especially online.

The musical mounted by the Philippine Educational Theater Association (PETA) takes the risk of following Hector (Myke Salomon) — a cash-strapped man who turns to online trolling for money. While work for the pro-Martial Law firm run by Bimbam (Vince Lim) initially goes smoothly, things become complicated when he struggles to keep his employment a secret from his activist friend Cons (Gold Villar Lim) and his estranged mother (Upeng Galang-Fernandez, unendingly moving), a former activist during Martial Law. When the specters of history begin to haunt him, harsh truths force Heck to confront his decisions and reevaluate his principles.

But when one looks at the rest of the writing, things reveal something much darker about our culture.

Insufficient intentions

Judged by its intentions alone, A Game of Trolls is a success. Constructed as an educational musical “for millennials” (Note: I think they meant Gen Z), the work exhumes the stories of Martial Law victims, brings them to life through magic realism, and supplements them with the careful research of Michelle Ngu. Liza Magtoto’s script and Vincent de Jesus’ music and lyrics are loaded with vivid details of the time — first told through oral history then later recounted by the victims themselves, the apparitions facing not only Hector but also the audience. The imperative for its creation is felt throughout and is commendable, even moving at times.

But art cannot rest on intention alone and must also be judged according to its content and form.

It must be said that A Game of Trolls wasn’t meant to be viewed in this way. Released on the 55th anniversary of PETA, this filmed version was, as with many theater productions in the country, a recording clearly meant for internal consumption only. Most productions do not have budgets for the kind of audiovisual equipment that helps create high-quality archival footage (a problem to be discussed another time). The result is a musical whose impact is lessened — especially as the editing haphazardly cuts from one camera to the next, disrupting the dynamics of the play’s most emotional moments and obscuring the choreography (by Dan Cabrera) with little reason.

But what is most disappointing is how Liza Magtoto’s script and Vincent de Jesus’ music and lyrics are near unintelligible due to problems with sound mixing. Considering each line and lyric contains valuable historical information, one wonders why the filmed piece did not have subtitles (Rak of Aegis had these). The absence of such an option leaves few of the details retained, as the production continues to be an assault on the senses.

Refusing ambiguity

The disinformation landscape is plagued with moral gray areas. Art has always been a medium through which ideas can be introduced, challenged, and even dismantled, and A Game of Trolls takes a clear stance against dictatorship and the machinery that has upheld it — opting to create a division between those fighting for the truth and those who are spreading lies. Hector finds himself caught in between these two worlds due to the necessities of survival, and the production takes every opportunity to point out his inaction and complicity.

In a 2017 interview, director Maribel Legarda addresses the need for this directness in attack, saying: “If the government’s not vague, why should we be?” These clear-cut divisions come at a price. Instead of displaying, commenting, and critiquing the material conditions that disenfranchises the poor, forces the poor to participate in “trolling,” and encourages them to uphold the same systems that kill them, A Game of Trolls opts for the easy route — putting the blame on the individual.

Rather than introducing to us other ways of fighting the battle against historical revisionism, it spends its time shaming those who are betrayed by the systems of education and disinformation. Though each specter that visits him plants a seed of doubt a la Christmas Carol, Hector decides to abandon his work not because he was convinced of the facts or believed in the stories but because his actions had endangered the lives of his loved ones.

This does not create an image of empathy but rather one of guilt ,and the resolution comes not from a sense of understanding history and the larger responsibility of standing by the truth, but rather from familial and filial obligation. By depicting an individual awakening rather than a spark towards a revolution, A Game of Trolls spoonfeeds its message to its audience. It fails to imagine them as more intelligent and discerning and reflects some of PETA’s outdated misconceptions about the youth and what they respond to.

Missing discussions

To write about how A Game of Trolls struggles to balance its need to educate and its strength as art is to uphold the necessity of storytelling and is an act of preserving the human rights of the people from whom these stories are borrowed from. Paraphrasing the Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Emily Nussbaum, criticizing the art form and the artists behind it is a way to hold it and its subjects in high regard.

Art has always had a place in shedding light on political realities. From the struggles in the slums in Rak of Aegis to the plight of queer overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) in Care Divas, PETA has, in the past, created hilarious and moving work without sacrificing accessibility and incisiveness of critique. But with A Game of Trolls, PETA fails to utilize the power of art, specifically theater, to humanize what people only come to know as statistics or facts in a book; to shed light on gray areas and morally dubious acts; to start and help navigate difficult conversations; to reach out to even those who are not educated through music and performance.

Maybe these are criticisms that are easier said in hindsight. But when one looks at the rest of the writing online about the play, many are closer to a press release than actual criticism (save for long-time theater critic Vincen Gregory Yu, always no-bullshit and incisive, and the recent review of Wanggo Gallaga that focuses on narrative structure). What seems to surface is a refusal (or an inability) to discuss and criticize the insufficiencies of art as, in the words of Fred Hawson, “a tool for historical instruction.”

The question isn’t “Why tackle Martial Law?” — there is enough denialism to prove that it is essential to discuss it, repetition bearing more weight as the elections draw nearer, as corrupt individuals grow closer to returning to power. The question no one is asking is: “Why a Martial Law musical?” Why this over an article? A book? A song? A poem? An illustration? A film?

After watching A Game of Trolls, I struggle to find an answer. – Rappler.com

A Game of Trolls will be available on April 22-23, 2022 via KTX.ph.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Sheila Coronel on fathers, daughters, the Marcos family and ‘mine’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/02/TL-fathers-daughters-marcos-family-February-26-2022.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.