SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

AT A GLANCE:

- Keeping up with erratic weather changes is hard, but obtaining insurance and loans to cover for losses is proving to be trickier

- The impact of banks’ non-compliance with mandated credit are now more pronounced given climate change

- Area-specific weather reports translated in the local dialect and implementing projects using a “climate lens” are some of the ways to deal with a world that’s changing for the worse

Farming is inherently risky. One needs to keep crops safe from pests, compete with cheaper imports, deal with typhoons, and carry most of the financial risk.

But despite the high risk, agriculture was the star among sectors amid the pandemic-induced recession. Farm output posted growth, while services and industries tanked by double digits.

But with climate change brewing up more typhoons and raising temperatures at a more erratic pace, poor Filipino farmers find it harder to produce food for the nation.

This year alone, typhoons have wiped out P14.25 billion in agricultural goods, according to data from the Department of Agriculture (DA).

The figure is already higher by at least P4 billion compared to the P8.1 billion in agricultural damage due to typhoons for the entire 2019.

With the El Niño impact, agricultural losses mounted to over P16 billion in 2019.

The recent onslaught of Typhoon Ulysses (Vamco) has damaged at least P400 million worth of rice in Cagayan and around P300 million in Isabela, preliminary data from the DA showed.

In total, Ulysses wiped out at least P4.2 billion in agricultural goods, nearing the P4.7 billion damage by Super Typhoon Rolly (Goni).

“Parang wala nang cycle ng pagtatanim, nasisira na, kasi bigla na lang uulan, babaha… may mga naisalba naman ang ilang magsasaka nitong mga nakaraang bagyo pero lugi pa rin talaga,” Jason Cainglet, executive director of Samahang Industriya ng Agrikultura (SINAG) told Rappler.

(It’s as if there’s no more cycle for planting because rain and floods have become unpredictable…farmers were able to save some produce before the recent typhoons, but it’s still a net loss.)

On average, around 20 cyclones enter the Philippine area of responsibility, of which 5 to 7 are destructive, according to the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration.

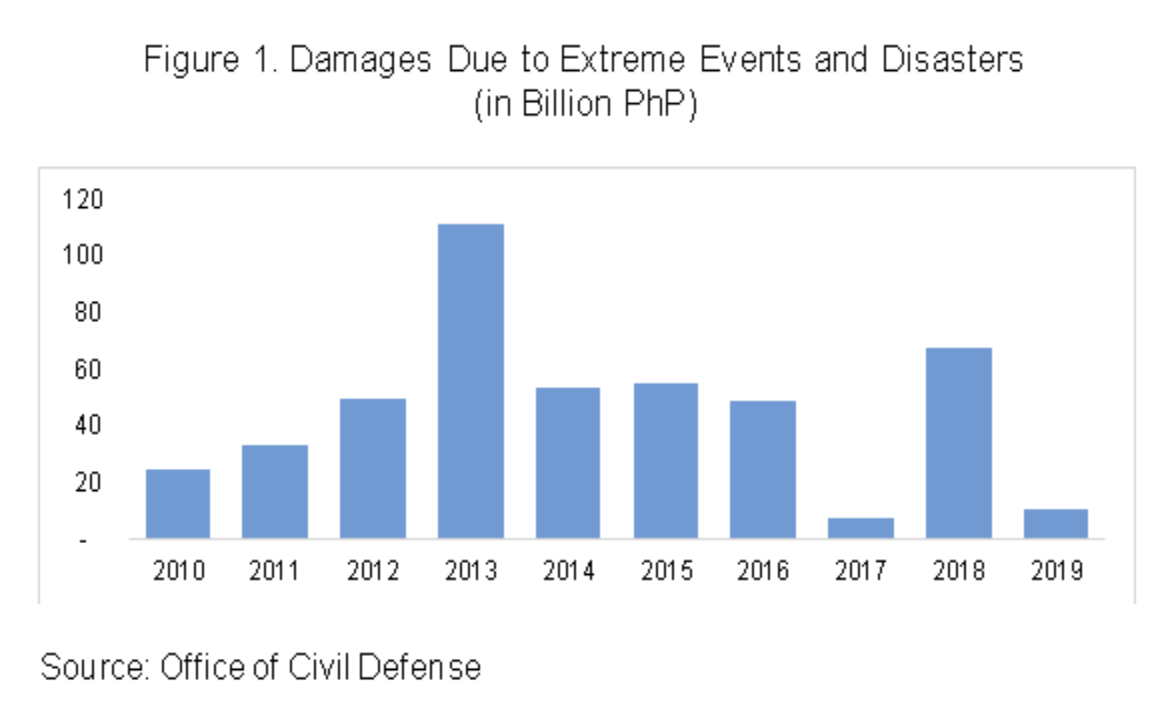

From 2010 to 2019, agricultural damage incurred due to natural disasters has mounted to P290 billion, data from the Office of Civil Defense collated by the Philippine Statistics Authority showed.

Damage to agriculture is 62.7% of the P463 billion total losses due to natural disasters. Damage to infrastructure amounted to P106 billion (23%), while communications lost P66 billion (14%).

Compared to the previous decade or between 2000 to 2010, agricultural losses amounted to P106.9 billion. This means that on a decade to decade basis, agricultural losses jumped by at least 171.3%, excluding figures from 2020.

Unfortunately, the problems does not end with natural disasters.

The financial losses would have to be shouldered by the poor Filipino farmer. Worse, the farmer has taken out a loan and has nothing to sow.

Crop insurance

Experts have long pushed for better insurance coverage for farmers, as it would manage risk and provide guaranteed payment in the event of natural disasters.

But the Philippine Crop Insurance Commission (PCIC) was always lacking in budget and manpower.

For 2021, PCIC is set to receive an allocation of P4.5 billion to provide insurance premiums to 2.1 million subsistence farmers and fisherfolk.

The proposed budget for next year is higher than the P3.5 billion in 2020, as the DA requested the Department of Budget and Management to allot additional funds from the excess rice tariffs collected in 2019.

But Cainglet said that the budget should be “multiplied tenfold,” considering that the losses are historically much higher than the yearly allocations.

Cainglet also noted that the government may have been too careful in abiding with World Trade Organization (WTO) rules on subsidies, hence the low insurance coverage.

“But in the last 10 years, all countries shifted, 60% of subsidies go to risk coverage and insurance and they don’t do direct payments, so they don’t violate WTO rules,” he said.

But perhaps the biggest hindrance of all is the farmers’ lack of awareness about the existence of PCIC, let alone how insurance works.

“The lack of awareness is not only about the crop insurance program as a whole but also the mechanism for availing, how to claim for indemnity, and its benefits. The literature also cites that the failure of farmers in filing for indemnity claims is partly attributed to their lack of knowledge on how to file for one,” a 2019 discussion paper of the Philippine Institute for Development Studies noted.

Loans, dole outs

If getting coverage insurance is hard, obtaining loans would probably either be the last resort, or not a choice at all.

Here are some of the DA’s loan programs:

- SURE COVID-19 – P25,000 zero-interest loans payable in 10 years

- Kapital Access for Young Agripreneurs – Up to P500,000 zero-interest loans that can be paid for 5 years; for agri-fishery college graduates that need capital

- Agripreneurship loan program for Overseas Filipino Workers – P300,000 to P15 million zero-interest loans payable in 5 years

Meanwhile, state-run Landbank of the Philippines, so far, has loaned close to P35 billion for small farmers and cooperatives in 2020.

To avail of the loan, farmers need to submit documents, including details on type of crops and return on investments. But the struggle for the poor farmers, perhaps, is the most basic requirement of all: an ID which many of them don’t have.

Meanwhile, commercial banks would rather pay penalties to government rather than provide loans to farmers.

Under the Agri-Agra law, banks should set aside at least 15% of their total loan portfolio to agricultural loans and 10% for agrarian reform beneficiaries.

As of March 2020, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas figures showed that compliance is only at 11% for agricultural loans, and less than 1% for agrarian reform.

Because of the non-compliance, banks have paid at least P5 billion since 2014 for penalties – a meager amount compared to their massive asset size.

Robert Sanders Jr, research associate of the Institute for Leadership, Empowerment, and Democracy, Inc (iLEAD), said that the non-compliance with the Agri-Agra law translates to almost P1 trillion worth of loans not being given to the agriculture sector.

For struggling farmers who unfortunately cannot get hold of a credit line, government has historically given dole outs.

Most recently, Senate Agriculture Committee Chair Cynthia Villar urged fellow lawmakers to use excess collections of around P3 billion from the Bureau of Customs as cash assistance for farmers in Cagayan and Isabela who were affected by recent typhoons.

Villar, however, emphasized that only those with land one hectare or below will be eligible for the cash assistance.

Financial solutions

Senators have attempted several times to pass a law for climate-based insurance, but none have materialized so far.

In 2018, Villar pushed for crop insurance that considered weather conditions as a trigger for indemnification claims, with trigger points determined by PAGASA. Once that threshold is breached, insurance providers would be obliged to make a payout to farmers.

The government would shoulder the premium, but farmers should inform the municipal or city agriculturist at least 45 days before the start of crop planting. The bill has, however, stalled, along with other similar proposals.

Senate economic affairs chair Imee Marcos filed a similar bill in 2019. The bill provides that farmers need not wait for a state of calamity to be declared or agricultural damage to be assessed, before they can collect on their insurance.

“A farmer would be able to automatically avail of payment even at the height of a typhoon, as soon as predetermined rainfall and windspeed thresholds are reached in what we call an index-based system,” Marcos said.

Meanwhile, Senator Francis Pangilinan sought in 2019 to make insurance mandatory for palay and other crops essential to food security.

Senate Bill 35, or the proposed Expanded Crop Insurance Act of 2019, seeks to amend existing laws which previously require crop insurance only of farmers who avail themselves of production loans.

“In case farmers are financially incapable, the National Food Authority (NFA) shall secure crop insurance for them. The NFA shall pay for the insurance premium and shall become at least a 50% beneficiary of the insurance proceeds or claim for all other crops,” Pangilinan said.

As for the Agri-Agra law compliance, proposals to amend it have started to gain traction in Congress.

Sanders echoed other proposals to drop the 15% and 10% loan allocation requirement. It should instead be turned into a 25%-across-the-board rule to boost bank compliance.

The power of information

Insurance and other financing solutions should be coupled with effective information dissemination.

Perla Baltazar, senior technical officer of the DA’s Climate-Resilient Agriculture Office (DA-CRAO), stressed the importance of localized agriculture-related weather forecasts and advisories.

Baltazar noted that some problems in communicating climate change issues include the lack of local translation of weather forecasts, and irregular dissemination of advisories.

Baltazar also noted that some of the DA’s projects like Climate Information Services (CIS) need to be scaled up and be implemented in more provinces.

CIS aims to build a common database to generate timely and reliable data for disaster risk reduction, planning, and management.

It also seeks to establish agro-meteorological stations (facilities that collect weather data to enhance agriculture) in highly-vulnerable areas.

Baltazar said that these programs, along with performing services “with a climate change lens” give better chances for farmers in an environment that is rapidly changing for the worse. – with reports from Jacob Reyes/Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.