SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

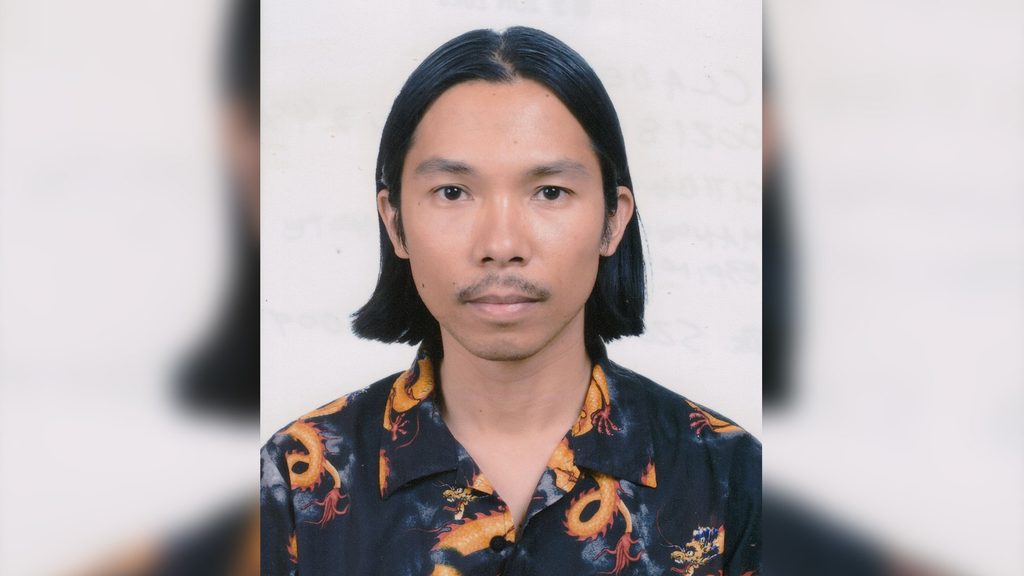

Miko Revereza sits on the sofa. It’s 8:31 in the morning. He and his wife Carolina rent a house in a small town near the mountains of Mexico. He is looking out at the terrace and the trees in the garden. On the table in front of him stands a makeshift vase containing wilting bougainvillea. He tells me that the documentary filmmaker Pacho Velez is visiting them for a few days.

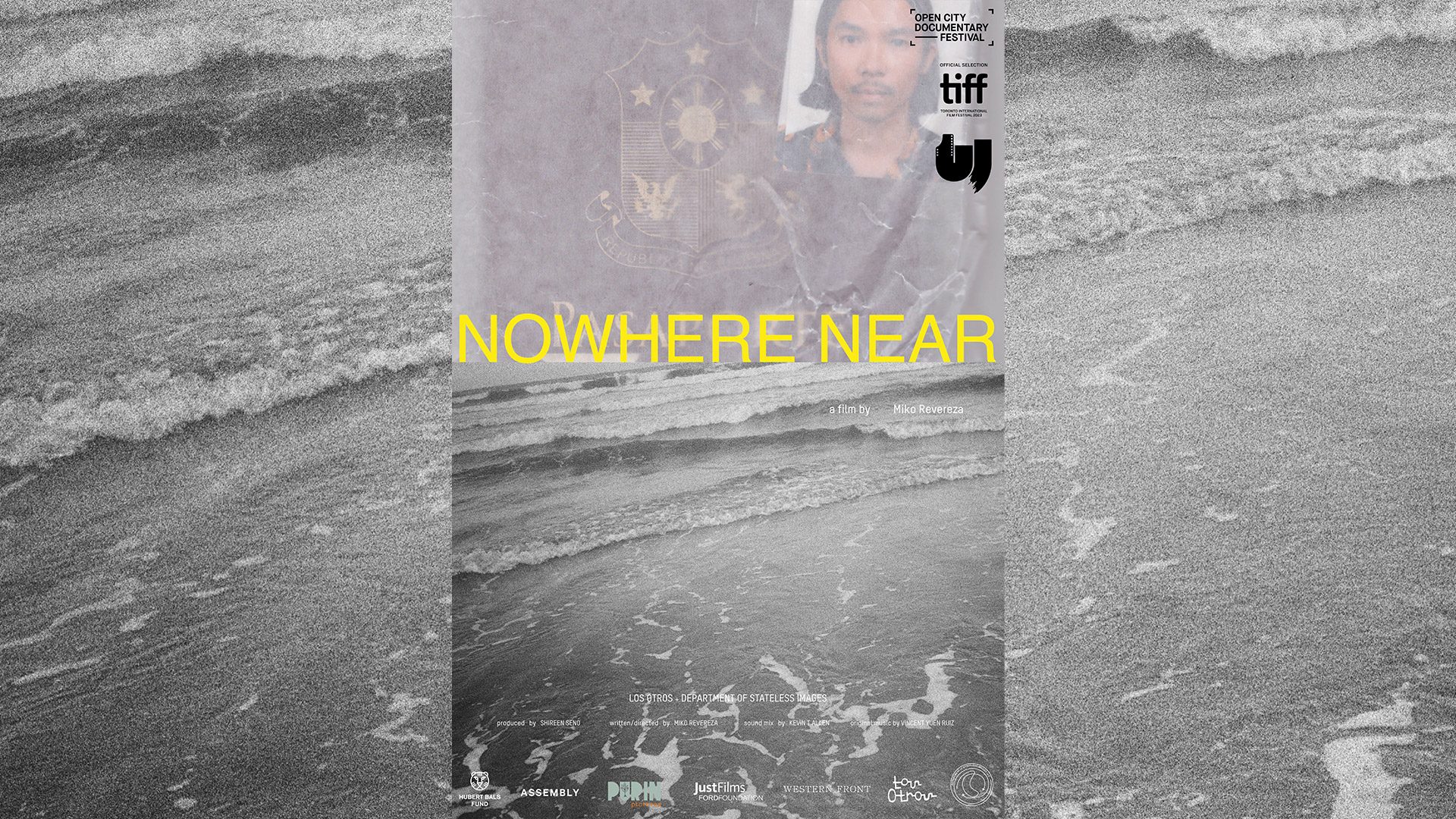

Meanwhile, here in Manila, over 14,000 kilometers away, I am quietly observing cars speeding and barreling through the tentacles of the city’s concrete existence, while reading Revereza’s responses to our email interview. Earlier today, smog blanketed the skyline. This, days after seeing Nowhere Near, the Filipino director’s third feature film, following El Lado Quieto (2021) and No Data Plan (2019).

Nowhere Near is set to premiere at the New York Film Festival this September 29. The film is seven years in the making but can also be seen as a sprawl through Revereza’s storied and nearly three-decade life, beginning in 1993, spent in the US undocumented.

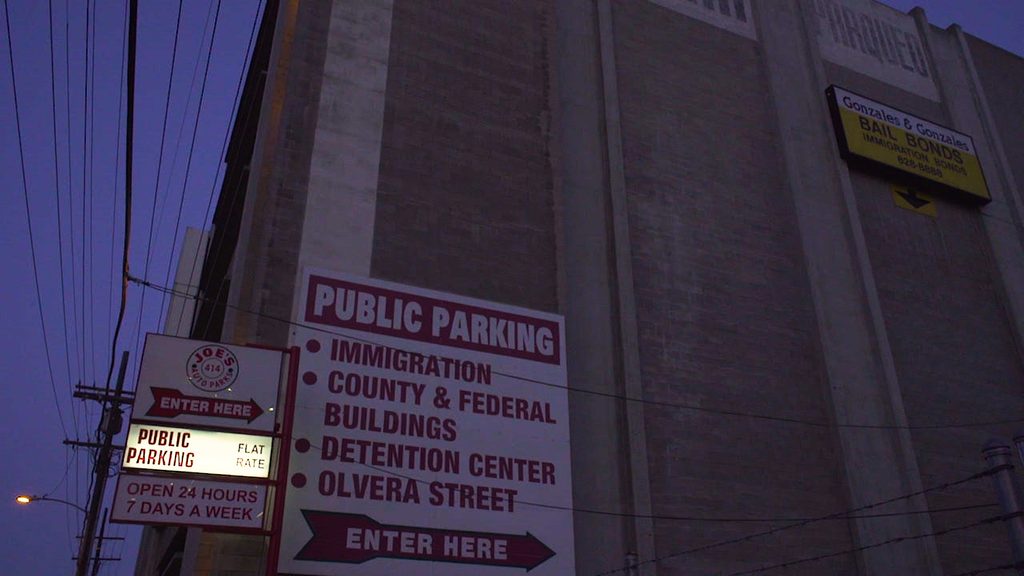

Part of Nowhere Near’s journey is told in his guerilla film No Data Plan, which recounts Revereza’s precarious travel from Los Angeles to New York via an Amtrak train, often subject to surprise ICE inspections. “The nowness of No Data Plan,” writes film critic Richard Bolisay, “does not only come from the present when people document nearly everything with their devices; it also emanates from the crises experienced by every Filipino forced to find their place and forge their identity in hostile lands.”

Unlike his previous features and experimental shorts, Nowhere Near sees the filmmaker coming back to the Philippines, patiently retracing memories now only dispensed in pixels and fragments, as well as histories outlined by so many years of colonization. He returns to once-familiar locations and points the camera to different surroundings occupied by anecdotes and experiences he now barely recalls, only for the lens to make its way back to him, capturing in the process what is both here and elsewhere, obscuring notions of home.

“In Nowhere Near, I follow my family in a futile quest to reclaim the past, as if home can only relate to the past. I needed to spend all this time thinking through the film in order to liberate myself from the sickness of our melancholia,” he says.

Revereza sees these stories, or at least versions of it, and, by extension, himself up-close yet he remains nowhere near.

In my interview with him below, the director talks about relating to Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño, how editing his own films hands him personal growth, and why these days he is “reconsidering soil.”

Q: Nowhere Near just had its North American premiere at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival, and is slated to screen at the New York Film Festival on September 29. How does it feel to finally have the film out there?

It is a huge burden lifted off my shoulders. Nowhere Near is the culmination of seven years of work. It is exciting to be experiencing the moments it finally hits the screens. I’ve left no stones unturned in the process of making this film and stand by every decision.

Q: You open the film with a quote from Roberto Bolaño’s Los Perros Románticos (1995): Había perdido un país pero había ganado un sueño (I had lost a country but won a dream). What does it mean to you?

Roberto Bolaño was an exile of Chile during the terrible dictatorship of Pinochet, with a similar timeline to the era of Philippine Martial Law. Bolaño made the decision to leave home with the intention of not returning. To lose a country is a heartbreaking thing, but to find your own agency in the world is indeed the dream. In the United States [where I spent most of my life as an undocumented immigrant], there was once a proposed bill that promised a pathway towards regularization of undocumented youth called the DREAM act. As an effect of this proposal, the generation of undocumented youth stuck in limbo were considered DREAMers. There were many iterations of this DREAM act throughout years but in the end it never passed. My family never saw the fulfillment of their dream of the United States. In Nowhere Near, I made the decision to exile myself from the US idea of DREAM to pursue personal agency.

Q: How long did you actually work on Nowhere Near, and did you also use footage from your previous films?

About seven years from filming to premiere. Within the time I made my other features No Data Plan and El Lado Quieto. In this sense, it is both my first film and my third feature film. No Data Plan was a segment of the larger journey of Nowhere Near takes. It does not reuse footage from the previous films but there is definitely footage from the same folders.

Q: The entirety of your work, including Disintegration 93-96 (2017), Distancing (2019), and No Data Plan (2019), has been an interrogation of the 26 years (1993 to 2019) that you’ve lived in the US as an undocumented immigrant. In Nowhere Near, you finally return to the Philippines, now probably more fraught with violence than ever. I’m curious about your idea of home after all this time.

I stopped thinking about home as related to a national homeland, while finding ways to stay connected across borders through the things that matter to me most, like film. The word nostalgia can be derived from the Ancient Greek theme nostos which relates to the impossibility of returning home from sea. Even when returning to that physical location, one mourns the inability to return to how it is remembered. Nostalgia is homesickness. In Nowhere Near, I follow my family in a futile quest to reclaim the past, as if home can only relate to the past. I needed to spend all this time thinking through the film in order to liberate myself from the sickness of our melancholia. Now I am thinking that maybe it’s best not to give so much power to the word home.

Q: The film’s sound design and score are so interesting to me, like the decision to mute some of the conversations and the inclusion of that clarinet refusing to be played. Can you talk more about this?

Sound is a dimension of cinematic play that can defy expectations and is very fun to mess with. I love working with layers of texture, foley, drone, and truly building up a lush sonic soundscape of an image, then all of a sudden stripping the next shot to silence. I think sound can be the subconscious association that accompanies an image. For example, there is a part there in the 9/11 segment of an audio clip of George W. Bush with the sound of TV static. In actuality, the TV static is a recording of crackling fire, which resembles TV static very closely but could carry overtones of war. Sound is where I can sneak content into the film. That was only one example but there is so much more hidden in there.

Q: Your films bridge experimental and documentary filmmaking. Can you share how you edit them, and what were the significant changes during the postproduction for Nowhere Near?

Though all the films touch on a similar thematic content, each of the films are very different formally. I edit myself because these are my memories and my primary intention is how the cut will affect me emotionally and contribute to personal growth. I come from a background and lineage of experimental film shot on film. I consider the Bolex camera as a musical instrument. While I shot my feature films digitally, they still carry values from experimental film such as the decisive moment, intuition and how the body moves the camera. When I’m editing the spacebar takes quite a beating. There are basic experimental techniques like double exposure that I found very useful in this film, towards constructing images with multiple meanings. I became interested not just in how images play next to each other but also on top of each other.

Q: Are there any Filipino filmmakers who influence your craft?

All the Mowelfund and post-Mowelfund experimental movements opened my thinking about film. Tad Ermitaño’s Retrochronological Transfer of Information (1994) in particular was mind blowing and leaves a mark on my films.

Q: Train rides and tracks are embedded in Nowhere Near and No Data Plan to document borders that are at once geographical, racial, and psychological. I’m curious about your most favorite image while in transit.

I am interested in the train as a metaphor for film. How the mechanism of tracks function similarly. Footage by name is a measurement of distance so in a sense, the apparatus of a moving image is also a mode of traveling.

Q: I observe that there are takes in the film that most directors would often cut out for being shaky or imperfect, but you seem to have this proclivity for incorporating precisely these types of images. What are your intentions behind this?

It’s a documentary. Even in fiction, I am not so interested in films that conceal how they are made and more importantly films where the filmmaker has the luxury of hiding behind the lens. I am interested in films that point to their own materiality and the struggle of the filmmaker. This is my taste in films and what gets me excited – when a film exposes itself.

Q: The film also contends with the complex relationship between the Philippines and the US, and how this relationship extends to your own family (ergo, their notion of the “American Dream”). How important is it for you to examine this through your craft?

As a Filipino filmmaker, I have to contend with the fact that this medium colonized us as much as guns and bombs did. Hollywood images, cinema, and US propaganda colonized us enough for us to copy and repeat the process. I am returning to the Philippines “from Los Angeles of all places” to make a movie. As much as the film is personal, I am reflecting on the problems of cinema.

Q: You authored a book of the same title discussing your process and journey to creating Nowhere Near. When is it coming out, and how different is it to account for everything in print instead of just capturing it through the camera?

It will come out by the end of the year hopefully. The book is much more expansive literally and poetically and isn’t bound to the format of a feature film.

Q: In a 2021 interview with Aaron Hunt, you compared your approach to filmmaking to that of “accepting the tangle of the mangrove.” Has this approach changed since then?

Kawayan de Guia and I once had an exchange by the campfire where I admitted to him that I don’t have any roots and he replied something like, “yes you do, you just don’t have any soil.” This was food for thought for some years, thinking about roots without soil. I also thought about Abbas Kiarostami’s statement about uprooted trees not bearing fruit, or if they do, not bearing fruit as good as if they stayed in their original country. I related to the mangrove as a way of being rooted in the tides. The currents of water is a recurring motif in Nowhere Near. These days I am reconsidering soil. Carolina and I are working on curing the fruit trees in the garden of the house we moved into. The soil needs to be worked and turned. Roots need space to grow. When soil becomes hardened and roots are stuck, the tree will also become unhealthy. This can relate to filmmaking, the cutting and displacement of images to grow new meaning. It took years of movement and processing but finally I am seeing the fruit of this labor.

– Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.