SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Minor spoilers ahead.

I can’t recall the last time my father said that he was proud of me, if at all. Growing up queer, I was wired to think that I had to over-achieve things to compensate for my queerness, to always end up top of the class, because it was the only way I knew how to get my father’s acceptance and, by extension, that of my family’s. Or perhaps I simply wanted him to say that I need not fret over it, that I never had to accomplish those things, that there was nothing wrong with me.

But, you see, my father is a man of silence. It’s the language he conveniently retreats to whenever he tries to distance himself, even from his loved ones, until some weight grows inside him, until he can no longer bottle things up. And I hate to admit that I’ve inherited this tendency from him, partly because I know how potent silence can be, how it can create a facade that sad things can be contained.

I say this now with a sober frame of mind but wounded and hurting all the same. And these days I still disappear into the years when I, like a stubborn kid, tried to remedy this ache, to find a faint semblance of healing, to hand grief a shape — but to little avail.

All of this rushes at me like cruel rain after revisiting Aftersun, writer-director Charlotte Wells’ debut feature. And I cannot help but return and listen to this playlist by Apa Agbayani, JL Javier, and June Bulaon in an attempt to articulate the throb of pain that has towered over me after the final frame, to parse the many things it cracks open. And maybe the reason why I can’t string any coherent insight about it before is because I refuse to come to terms with the relationship I have with my father. How beautiful and frightening it is to be reminded of cinema’s power beyond narrative function, beyond the array of images it presents onscreen.

In the world that Wells constructs, memory is neither here nor there yet forever in tow, so fickle and malleable, and always dispensed in fragments. Sophie (Celia Rowlson-Hall), now in her 30s, recollects a Turkish vacation she shared with her father, Calum (Paul Mescal), two decades ago. Armed only by an old camcorder they used to toy with, she clings on to this memory — and I mean both the remembering and un-remembering — precisely because sense and comfort are not possible elsewhere. So we, dear viewers, allow ourselves to look at things the way young Sophie (Frankie Corio) does. Here, what’s real and imagined are besides the point. Because every ray of Aftersun is nothing but an attempt to understand what we can about the people that we hold dear in our hearts.

Wells’ ways of seeing lucidly evoke that, capable of finding complex textures in the simplest of moments. Her images, in its precision and intimacy, gesture a certain restraint enough to keep the looming tragedy at bay, to provide the film some level of ambiguity but never at the expense of meaning. And Wells depicts pain here as dormant, like wires waiting for current to flow, often placed in tiny, private instances: from the heartache of having to walk idly in the dead of night, to the shame of wanting things and not having the purchasing power, to the desperation of lighting a cigarette to accompany your loneliness, to the regret of not sharing a song with a loved one.

This cinematic timbre has always been part of Wells’ arsenal, especially if you take a look at her short films, including Tuesday (2015), Laps (2017), and Blue Christmas (2017). These works, when seen as a whole, demonstrate her ability to tap into every emotional fiber, no matter how hard and deep, and to access the fragility of the human condition with incredible sensitivity. But it is in the bittersweet Tuesday, which tells the story of a college student dealing with her dad’s loss, that Aftersun finds its first sorrow, its initial contact with damage that is often beyond repair.

And so much of the film works because of Mescal and Corio’s radiant dynamic such that they’re able to keep each other at ease, while maintaining this visible friction between them. It’s almost as if their connection is lyrical, always attuned to each other’s emotional beats. Corio’s gift lies in the rawness of her work, in the authenticity of how she peels away her character’s motivations.

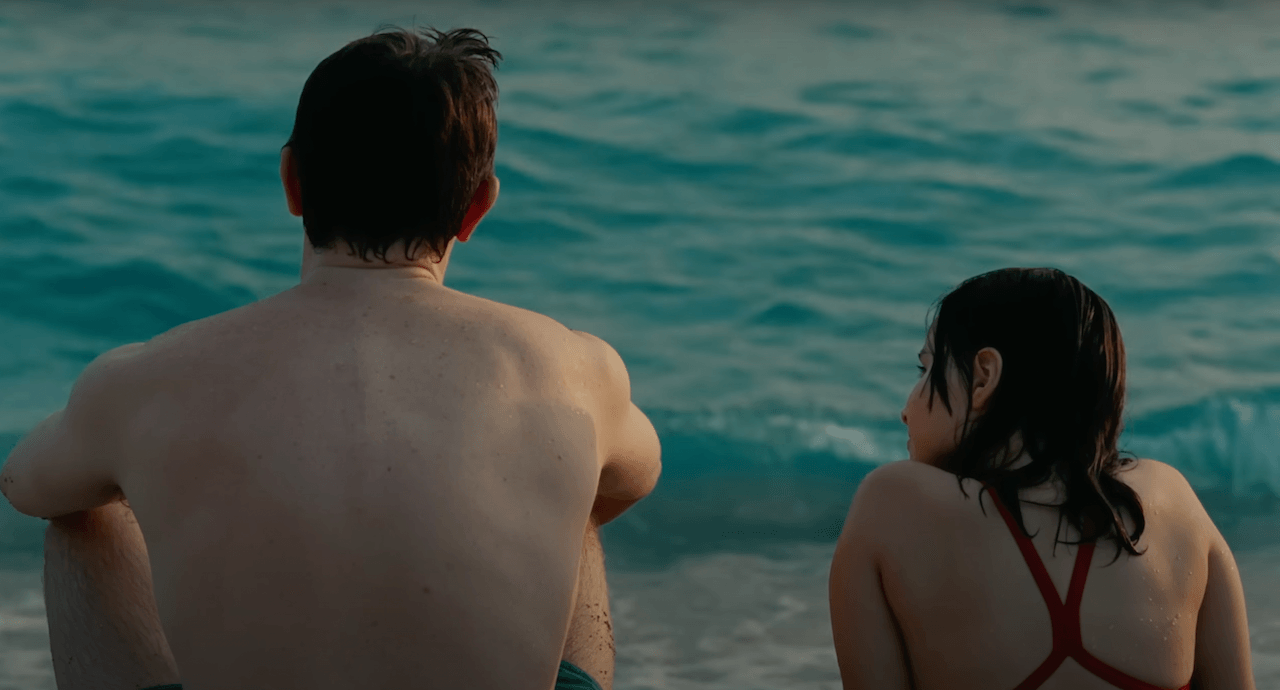

Mescal, on the other hand, is nothing short of impressive. In one of the film’s most heartbreaking moments, we see Calum, all alone in the hotel room, emotionally combust and weep his heart out. We only ever gaze at his back, unclothed and slack, yet we still feel the enormity of his pain, the shape of every sob. Such depth and intensity to which Mescal anchors his character simply confirms that he can offer way more than what is expected of him, something he had already made a strong case for in Normal People, so effective that he can make even something as mundane as observing a carpet feel so heavy and devastating.

The film, owing mostly to the artistry of cinematographer Gregory Oke and composer Oliver Coates, consistently weaves this rhythm, treating its characters with such humanism and care, and never resorting to cheap impulse. There’s something so gentle in the way it navigates the flaws of its characters, the very things that make them feel seen, conveying that a love that never passes is the kind that is never refined. It has this way of looking at its audience with a set of eyes that are never prying and never intimidating.

And maybe the reason why I deeply gravitate towards Aftersun is because I envy these imperfect yet wonderful moments between Calum and Sophie, these possibilities a father and child can have, the tenderness they both share. Because a part of me still longs for the day that I can also look back on happy memories with my father, never mind how hazy they might become. What’s important is at least I know I once had them. Maybe it’s all just wishful thinking, but better that than the cruel alternative.

So much of this weight leads me back to the film’s closing frame, to think about the multitudes it carries, the desperation in its one final look. In the end, we’re nothing different from Sophie. Because like her, we’re all just trying to hold this one final, fleeting image of the person that we love, and thinking why we continue to love them, despite the gnawing awareness that we may never be able to truly understand them, despite the fact that our memory may one day turn its back on us.

So again, one last pan shot of this moment, of this person, as if everything is finally making sense. Slowly going, going, gone. – Rappler.com

‘Aftersun’ is currently screening at FDCP Cinematheques and select cinemas nationwide. Check out the FDCP Facebook page for more details.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.