SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

It’s a double whammy for performing artists to have their work plagiarized in the time of pandemic – on top of having no gigs, they are cheated out of possible royalties at a time when they need it the most.

That’s why many conversations among Filipino performing artists nowadays focus on the implications of the alleged plagiarism by The Pop Stage winner CJ Villavicencio of an Eraserheads musical.

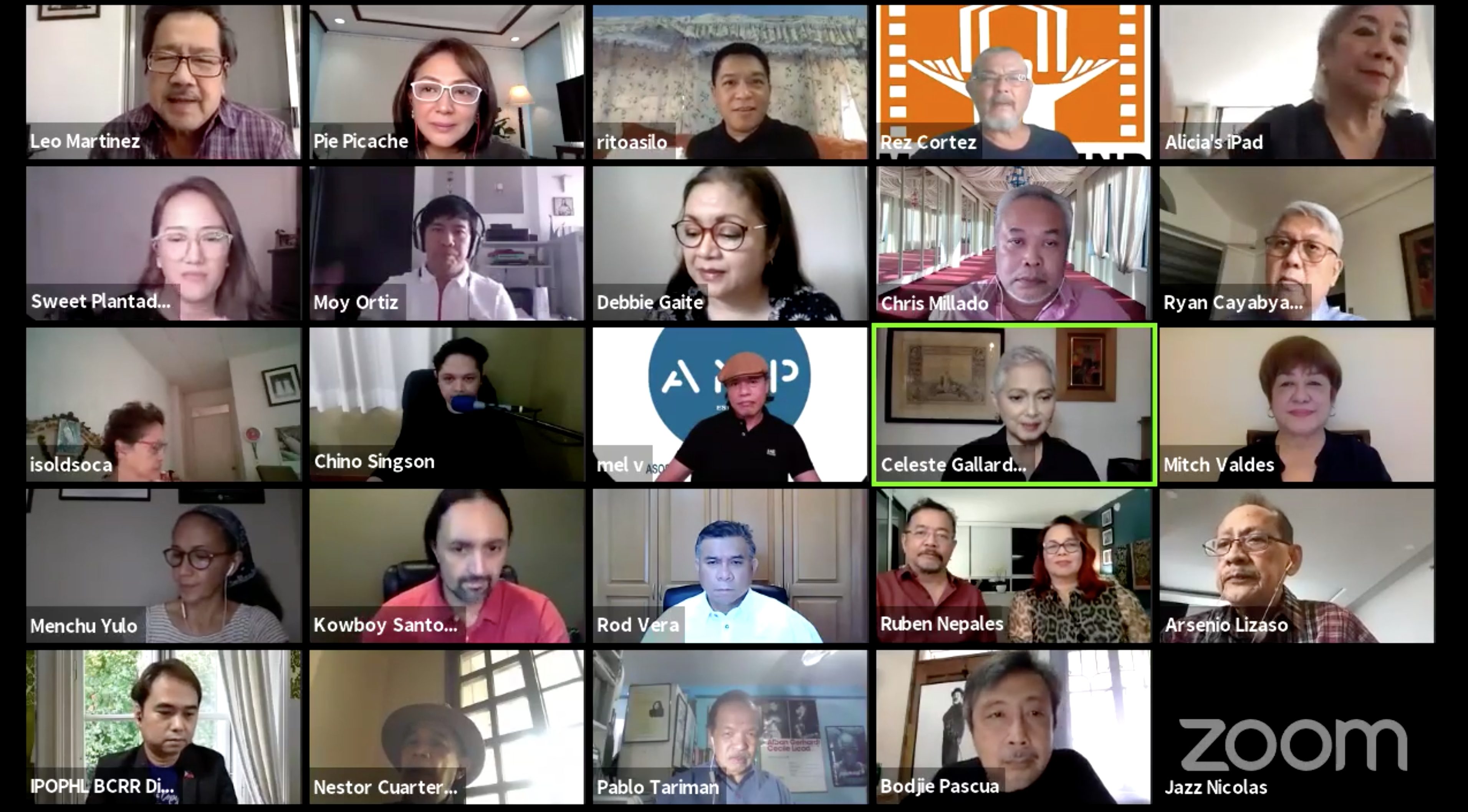

In a discussion on Saturday, August 8, the Performers’ Rights Society of the Philippines (PRSPH), performing artists asked legal experts about negotiating of “questionable” contracts to existing gaps within the Philippine Intellectual Property Code (IPC). Experts in copyright and intellectual property like Debbie Gaite and Atty. Rod Vera gave advice to artists like actress Iza Calzado, musician and composer Ryan Cayabyab, and Itchyworms drummer Jazz Nicolas.

Briefing performing artists on protections afforded to them by the IPC does not happen as often as it should in the Philippines.

Singer Mitch Valdez said that “the Philippines needs to be a little bit updated regarding our performers who do not really, or are not aware of their rights. In the international community, this is already standard practice.”

Plagiarism in political campaigns and asking for compensation

High-profile violations of intellectual property rights in the Philippines have even extended into the political realm. During the 2019 midterm elections, Sandwich frontman and former Eraserhead Raymund Marasigan called out campaigns for adapting original songs into jingles.

In the United States, artists like Adele, The Rolling Stones, and even the estate of the late artist Prince have also publicly called out President Donald Trump’s campaign staff for playing their songs without permission.

The discussion extended beyond plagiarism and also touched on the economic benefits of intellectual property rights.

As an accredited and registered copyright management organization (CMO), PHILSCAP is primarily intended to collect the remuneration rights of artists.

Valdez cited her own experience in the late 1990’s as one of many which led to the formation of PRSPH. She and a few other artists approached then-senator Raul Roco, a relative of singer Celeste Legaspi, to seek legal counsel about getting compensated for replays of their performances on various local stations, only to find out that Roco was already in the process of filing the IPC in the senate.

Valdes said Roco inserted in the bill “remuneration for performers” at the last minute.

With former senator Roco’s filing of the IPC in 1997, performing artists were given the right to seek remuneration for the broadcasting and rebroadcasting of recorded or filmed performances.

Without the PRSPH, Valdes said that it would be “very difficult for each performer to go to each broadcast studio or record label producer and demand a certain number of rights. Which, by the way, you would have to submit proof of your works, how many times it was played, and all of those things. Therefore, PRSPH has taken on the responsibility of doing all of this for you.”

Producers’ liabilities

On the other hand, talent manager and agent GR Rodis raised questions during the open forum about the responsibilities of film producers like herself and Celeste Legaspi in compensating hired actors for re-broadcasts of films.

“Ang Larawan was a very expensive movie to produce. Until now, we haven’t made up – gotten back – our full investment in the film. We’ve only been able to collect about 80% of what went out. Now, as part of what we did to afford the film, we sold the rights to ABS-CBN, the digital rights to ABS-CBN for 15 years,” said Rodis.

“How do we pay them?” she asked. “I mean, we didn’t even make any money from it, except to finance the movie and the marketing of it? What happens to us? What is our liability as producers?”

Copyright expert Debbie Gaite told Rodis that the broadcasting company is liable for the payment and that PRSPH’s role in this case would be to negotiate and collect the licensing fees from ABS-CBN for re-broadcasts.

Performers’ rights in the pandemic

Economic benefits of these rights, like the collection of royalties, are all crucial for performing artists in the time of the pandemic. As actress Cherry Pie Picache said, “Maraming nagasasabi na sa simula ng pandemya, ang entertainment industry and unang nagsara. Sa pagsasarang ito, libu-libong manggagawa sa telelebisyon, pelikula, at digital platforms ang nawalang ng hanapbuhay.”

(Many have said that at the beginning of the pandemic, the entertainment industry was the first to close. With this closure, thousands of workers in television, film, and digital platforms lost their livelihoods.)

Picache and Asosasyon ng Musikerong Pilipino president Mel Villena also spoke of the challenges imposed by lockdowns upon supporting actors, extras, and session musicians, whose essential contributions to the production of art may not be immediately visible.

Villena said in a mix of Filipino and English, “They just want to play! Now these people, there are several hundreds of these people now asking for help. Now, how are we going to be able to help them? That’s the question.”

Picache and Villena appealed to their colleagues, inviting them to support PRSPH’s initiatives and accept assistance from the society to help collect royalties and residuals from their recorded works.

Composer and musician Ryan Cayabyab echoed this invitation, extending it specifically to younger Filipino artists, performers, and musicians, who are just beginning to accumulate residuals for their work.

“Can you imagine? Everyone that is here is a cardholder already, meaning that they have experience. They have the time to work for you, to take care of your rights,” said Cayabyab in English and Filipino.

Creating a ‘cultural industry’

Aside from pandemic-related concerns, a number of guest speakers also discussed the future of performing artists’ rights in the Philippines.

Chris Millado, vice president and artistic director of the Cultural Center of the Philippines, spoke of the importance of copyright management organizations like the PRSPH in the push to create a “cultural industry” in the Philippines.

Millado said, “because we aren’t organized into guilds and associations, we haven’t come up with a system in terms of monetizing and really giving the proper value to the work of our artists.”

The establishment of central organizations that advocate for Filipino artists’ rights will thus help build clearer systems of value assignment for artistic works, which, in turn, will help artists receive appropriate remuneration for their work.

The underlying hope behind such a “strategic push” for centralization is that clear, organized systems will incentivize artists to participate in the construction and development of cultural industry in the Philippines. – Rappler.com

Ally Benitez is a Rappler intern, currently studying history at the Barnard College in New York.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.