SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

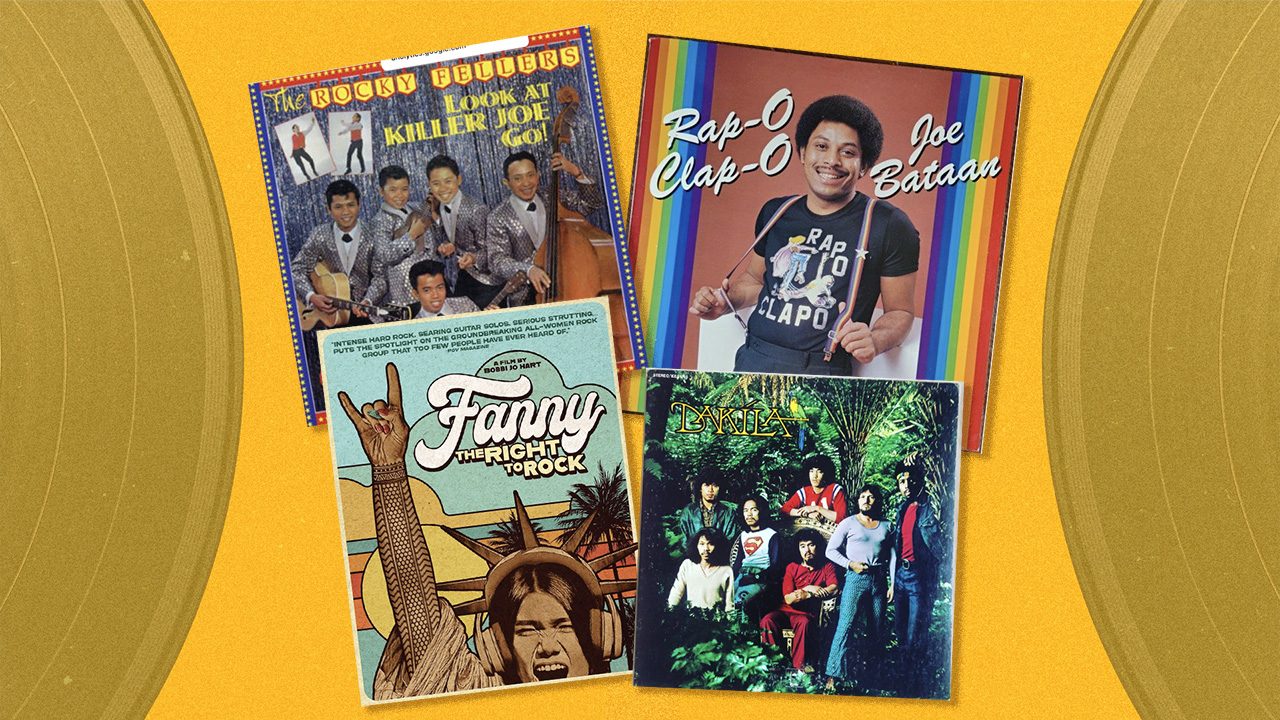

The Rocky Fellers, four brothers and their father surnamed Maligmat, were the first Filipino American act to crack the Billboard charts in 1963 with the song “Killer Joe.” But aside from short online magazine stories and a six-paragraph Wikipedia entry, little is know about the group and their musical journey to short-lived pop stardom.

For decades The Rocky Fellers and other pioneering Filipino American artists from the ’60s to the ’70s were like shadows on the brightly-lit stage of popular music, unnoticed and unrecognized even by their own kababayan in America. But that has changed.

Today, there is growing interest in their stories and music. To mark Filipino American Month this October, we look back on the careers of these trailblazing artists whose achievements are being feted by a new generation of Filipino Americans eager to reconnect and discover their roots, and write their own stories.

Joe Bataan: Ordinary guy

Born Bataan Nitollano, Joe Bataan was raised in East Harlem, New York’s Latin district. His father was a Filipino and his mother was African American, but he grew up to the sights and sounds of Latin culture.

Bataan hustled as a teenager and ran with a Puerto Rican street gang while soaking up the district’s heady mix of Puerto Rican, Cuban, and African beats, with servings of doowop, Broadway, and R&B thrown in. After doing jail time for stealing a car, Bataan embarked on a musical career, easily sliding from doo wop to boogaloo and soul.

Regarded as a trendsetter with a keen ear for the beat of the streets, Bataan scored a series of Latin soul hits that earned him the monicker King of Latin Soul in 1967 with the release of his first album Gypsy Woman.

In the ’70s, Bataan championed a new record label and a new sound, salsoul, a fusion of Latin, soul, and disco. In 1979, at the age of 39 and after years of absence, Bataan picked up on a new musical style from a community center party. He wrote and released “Rap-O, Clap-O,” regarded, belatedly, as one of the first rap songs ever recorded. The song became a hit in Europe.

It was also at this time that Bataan began to refer to himself as Afro Filipino, which was also the title of his 1980 album. It was a bold declaration of identity at a time when most Filipinos in the US would rather be seen as little brown Americans. Bataan continues to perform until this day.

Fanny walked the earth

Fanny was the first all-female rock group to be signed by a major label, releasing five albums and scoring two hits on the Top 40. They played in concerts alongside Jethro Tull and Humble Pie, and were famously name-checked by David Bowie in a 1999 Rolling Stone interview as “one of the most important female bands in American rock.”

“They were one of the finest fucking rock bands of their time, in about 1973. They were extraordinary: They wrote everything, they played like motherfuckers, they were just colossal and wonderful, and nobody’s ever mentioned them,” Bowie said. The band, he added, was “buried without a trace.”

Born in the Philippines, June and Jean Millington moved to California in 1961 and had to deal with racial prejudice all throughout their teenage years. The prejudice would follow them constantly, even after they had formed Fanny.

As an all-female rock band, Fanny battled with sexism. They can blow the roof off with their tight playing and June’s stellar guitar chops but they were dismissed by critics as a novelty act (one noted Rolling Stone critic called their music “cute”). At one point, they were asked by their label to wear more revealing clothes onstage. This prompted June to quit the band.

A re-formed Fanny would record one more album before fading into obscurity, but they opened the door for hard rocking female acts such as The Runaways, The Go-Gos, Suzi Quattro, Joan Jett, and Pat Benatar. A documentary titled Fanny Walked the Earth has been released to wide acclaim.

Dakila’s protest song

A documentary is also in the works for Dakila, a band from San Francisco’s Mission District and one of the finest psychedelic Latin rock bands. On their 1972 self-titled debut album on Epic Records, Dakila served up a unique blend of psychedelia, funk, and Latin beats with Tagalog lyrics on the song “Makibaka/Ikalat.”

It was the father of the Bustamante brothers, founding members of the band, who suggested the name Dakila, which is Tagalog for great or noble. Vocalist Romeo Bustamante, in an interview published on radio station KQED’s website, said the band wanted to declare at the onset their identity as Filipinos. They wrote “Makibaka/Ikalat” to reflect the tumult of the early ’70s, both in the US and in the Philippines.

His brother David, the band’s guitarist, described the song in a separate interview as “a message to the people to stop hiding and speak up because we are all brothers and sisters and to pass around the virtues of love, harmony, and peace.”

But more than reflecting social realities in their music, Dakila immersed themselves in the whirlwind of social movements in the Bay Area. They did fund-raising gigs for farm workers’ unions, and performed in assemblies for the nascent Asian American student movement. They were the first Filipino American protest musicians.

At their peak, Dakila played in festivals and at iconic venues such as Fillmore West and Winterland. They jammed with the likes of Santana, Malo, and Sly and the Family Stone.

While their first album was groundbreaking, most of the members were unhappy with the way the producers “mangled” the opening track, “Makibaka/Ikalat,” changing the pitch and added studio effects. Bustamante said they were also disappointed with a recorded Tagalog “pronunciation guide” given to radio station. The record, he said, played on existing prejudices and stereotypes of Filipinos. After the first album failed to gain traction, the label quietly dropped them.

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the first album, a remastered version has been reissued. The pitch of “Makibaka/Ikalat” has been corrected, and listeners can now hear this iconic song the way the band originally recorded it.

Music and stories

The stories of The Rocky Fellers, Joe Bataan, Fanny, and Dakila are stories of short-lived triumphs in the face of discrimination and racial and gender stereotypes.

Their music celebrated the promise and possibility of popular music as a true and inclusive expression of youth sentiment, a celebration of passion, community, and fun.

But as popular music grew in excitement, complexity, and creativity, as it plundered the musical traditions of other cultures, these Filipino American musicians who helped enrich the music found themselves left out or ignored. It is paradoxical that as rock and roll in particular, and popular music in general, expanded its musical canvass, the culture and the industry became insularly white and male.

A new generation of Filipino American musicians would later ground their aspirations on their distinct identity. In a nation whose enticing declaration of equality and freedom has proven elusive, and to some illusory, Filipino identity has become a wellspring of hope, purpose, and pride. – Rappler.com

Joey Salgado is a former journalist and spokesman for former vice president Jejomar Binay. He is a government and political communications consultant. This article was first published in ourbrew.com.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.