SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

When you enter Tanghalang Ignacio Gimenez, the first thing you’ll see is the backstage — mirrors set up on the side of the bleachers, costumes hanging on a nearby rack, and makeup splayed out on the dressers. The actors stand within plain view, looking at a woman speaking onstage, a pole wrapped in Christmas lights obscuring the eyeline. It’s a jarring image that contradicts the dichotomy expected of the theater — there is no glamor onstage to be protected, nor tumultuous behind-the-scenes ruckus to be kept secret.

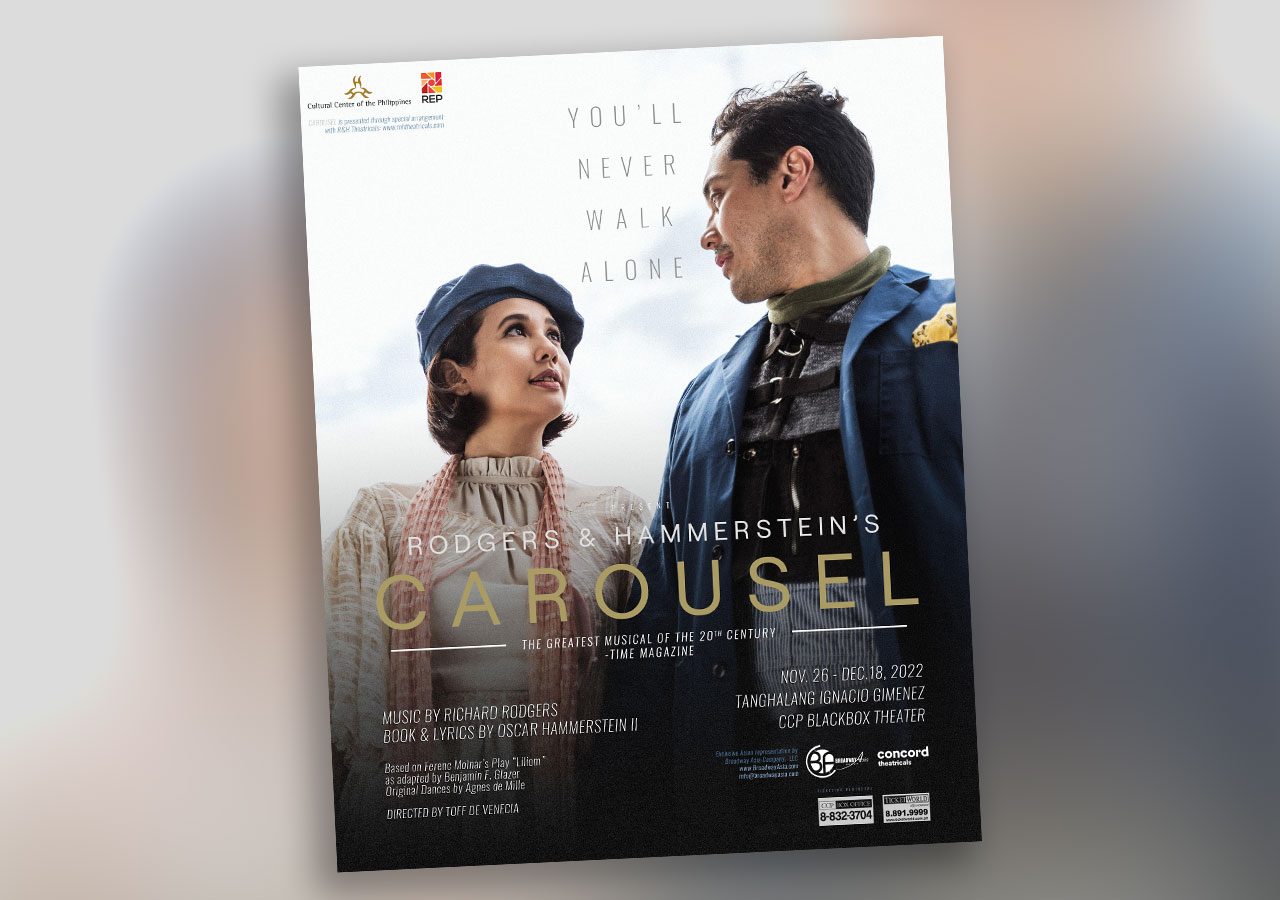

Prior to this evening, I was mostly unfamiliar with Carousel. Set in Maine at the beginning of the long depression of 1873, Carousel chronicles the lives of former millworker Julie Jordan (Karylle Tatlonghari) and carousel barker Billy Bigelow (Gian Magdangal) whose flirtations turn sour due to the economic downturn. Filled with romance and regret, Carousel is widely considered Rodgers and Hammerstein’s best work and was named the best musical of the 20th century by Time Magazine.

But rather than a straightforward romantic retelling, director Toff De Venecia uproots the classic from its context and places it squarely within the present, challenging the material’s place and politics in the 21st century. De Venecia’s staging strips it down to its essentials — using a beautiful two-piano score (played by Joed Balsamo and musical director Ejay Yatco) instead of a full orchestra and downsizing the cast from 30 to 14, most of whom double as human architecture amidst Charles Yee’s minimalist set design.

But more than anything, De Venecia pulls at loose narrative and thematic threads until they come undone, exposing the rotting bone beneath the romanticism — a story rife with misogyny, gendered expectations and violence, and turmoil internalized from the pressures of economic instability, all of which are characteristic of the post-Civil War America.

The devil is in the details. Costume designer Jodinan Aguillon mixes in contemporary garb and older pieces from the Repertory Philippines archives to tell narratives and create tensions in the anachronism. By dressing Tatlonghari in baby pink and having her behave with almost childlike innocence at the beginning, De Venencia emphasizes the disparity between Julie and Billy, their power dynamics imbued in their clothing, enabling the audience to see, especially now, how Macapagal’s Bigelow may be seen as a predator today.

At other times, the decisions hit you on the head again and again. Someone walks across the stage wearing a “My Body, My Choice” t-shirt during June is Bustin’ Out All Over. Some of them bring out cameras throughout the production as a means to reiterate the spectatorship, most notably in Geraniums in the Winder, where Enoch Snow (Lorenz Martinez) and Carrie Pipperidge’s (Mikke Bradshaw-Volante) relationship undergoes a trial by publicity. While this decision connects it to a poisonous history of he-said-she-said, its immediate parallels to Amber Heard and Johnny Depp’s trial minimize the severity of the case, almost trivializing the consequences of public opinion and the damaging repercussions of such exponential reach in the digital age. By making these mental connections in the audiences’ minds tangible onstage, it neuters the subversive power of the subtext and, at times, registers as distrust for the audience’s intellect.

But there are moments when the friction brought about by the differences in the text and direction creates something new. Like when choreographer Stephen Viñas creates movement that renders the cyclical nature of abuse tangible for Louise (Gia Gequinto) and her two lovers (Steven Hotchkiss and Julio Laforteza), an umbilical cord-like structure tethering her to her father’s dark past. The dance concludes with Louise being enveloped by a circle of light, one of many lighting designs by Barbie Tan-Tiongco that seemingly places her back in her mother’s womb. Or when the women appear onstage with their scripts, seemingly reciting lines memorized from Carousel itself, the repetition mirroring the performance of gender and the inescapability of these roles. Or when the singular Starkeeper is replaced by a Greek chorus of women in front of a ring light — a manifestation of Billy’s guilt, whose synchronized voices taunt and haunt him with his actions and inactions and who will be the ones who will ultimately judge his fate.

It helps that these formal experimentations are performed by a committed cast of talented actors, though their accents leave much wanting and the sound design renders some of their dialogue and songs garbled. Martinez and Bradshaw-Volante consistently provide the material with levity, enabling the audience to contrast their relationship with Julie and Billy’s failing one while also displaying how material security can cushion emotional dissatisfaction. On the other hand, Tatlonghari’s truth never wavers, even if she is burdened with the play’s most crucial and most affecting emotional moments, her entire character arc visible in the way her expressive eyes lose their light.

Admittedly, the affinity for these directorial decisions comes in hindsight, especially because I found it difficult to emotionally invest in the material. In the first act, the darkness of the staging seems to suck out the joy that Rodgers and Hammerstein often imbue their music and lyricism with. How was this made by the same people who adapted Cinderella into a musical and created The Sound of Music? At times, it is more enjoyable to talk about Carousel than it is to watch it; easier to revel in its intellectual and technical prowess after the fact than to be moved by it in the moment.

But the entire staging presents a valuable question for Filipino artists, one which films such as Todd Field’s TÁR and Elaine Castillo’s essay collection How To Read Now have attempted to wrestle with in contemporary times: Does art made by a bunch of cisgender white men in the past have a place in today’s society? Is it possible to be moved by Julie’s commitment to Billy with the knowledge that there was spousal abuse and marital dissatisfaction? Is it possible to appreciate any art in a time of moralism, even if its flaws make it problematic? What do our answers, questions, and fixations say about how we view art and art-making today?

We like to imagine that the America it is situated in is significantly different from our own here in the contemporary Philippines. Yet by placing the background of Carousel at the forefront, De Venecia has drawn parallels between the conditions that prevent young love in these two time periods from surviving and thriving: white supremacy, capitalism, and heteronormativity looming over the characters like a ghost ready to take over their bodies. When Carousel rushes to its conclusion of atonement purely due to textual demands, it becomes clear that this isn’t a Carousel for the kids, the romantics, or the Broadway purists. The message itself is rendered with incredible lucidity and bravery, even if you won’t always like what it’s saying and how it is said. – Rappler.com

Repertory Philippines’ Carousel runs til December 18, 2022 at the Tanghalang Gimenez Theater, Pasay City.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.