SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

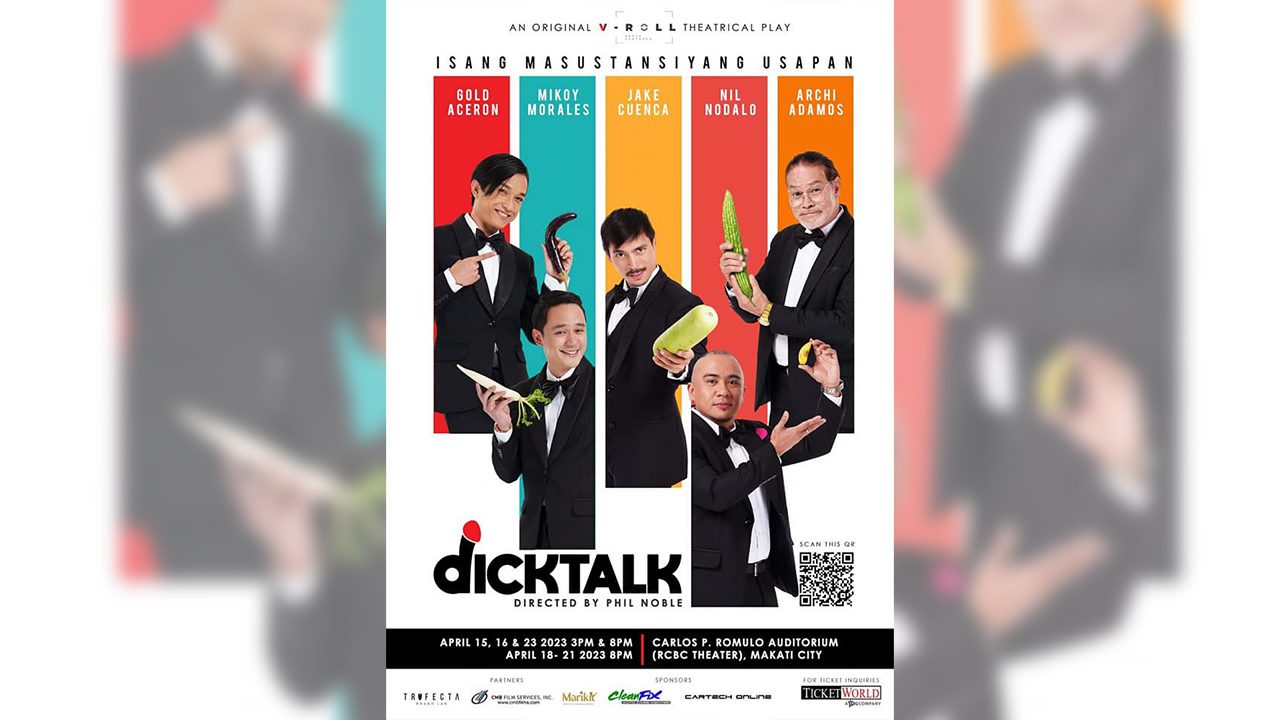

Before one even enters the RCBC Plaza, one wonders why a production such as DickTalk would be staged in the first place. In an earlier conversation with the press, concept creators Edwin Vinarao and Christian Clemente revealed that they began working on the production in 2020 and were inspired by The Vagina Monologues — the seminal feminist work by Eve Ensler written in 1996 that tackles several taboo stories concerning the vagina. DickTalk, in the words of its own artistic team headed by director Phil Noble, “aims to break stereotypes about men and revolutionize conversations around machismo and the male genitalia.”

It’s not as if people with penises aren’t allowed to speak. In 2004, Ricky Lee, in collaboration with director Joel Lamangan, created Penis Talks in response to Ensler’s work. While neither DickTalk nor Penis Talks share the same spine of in-depth qualitative research that makes The Vagina Monologues stand the test of time, Penis Talks was unafraid to get into deeply political territory. From transexual sex workers struggling with concealment of their genitals to men with dating difficulties due to their micropenises, it centered stories often left out of the conversation. Lee, who has always been a keen observer of gender dynamics and how these complicate moral living in the Philippines, understood that what made The Vagina Monologues evergreen was how it used discussions about genitalia as a gateway towards larger sociocultural conversations around the patriarchy, placing under the microscope what is often pushed out of the spotlight.

But the zeitgeist of the late ‘90s and early 2000s is vastly different from the one today. Whereas these stories were inaccessible to the public before, discussions around genitalia, sex, and penis-related issues have been much easier to access thanks to the internet and its various crevices. Considering that seeds for monologues can now be found in posts on social media and even on Reddit, DickTalk is faced with a difficult question: what else can it say about the penis that can’t be provided by a quick Google search?

Dicktalk adopts the same structure of The Vagina Monologues and features five monologues co-written by Benj Cruz Garcia and Ara Vicencio that center experiences of five men: the perpetually horny youngster with a curved penis Jun-jun (Gold Azeron), the trans man about to get top surgery Rob (Nil Nodalo), the metrosexual about to get married Cecile (Mikoy Morales), the aging man wrestling with the consequences of his infidelity Doods (Archie Adamos), and the hypermasculine sex worker involved in a road rage incident Peter (Jake Cuenca). DickTalk makes no attempt at concealing its upper-middle class leanings, opening with all the bachelors onstage, donning suits and holding glasses of alcohol, bragging about their sexual conquests with the kind of verve and debauchery reserved for golf courses. This alienating image sets the tone for what will transpire in the next two hours.

For all its good intentions, DickTalk struggles to live up to its inspirations. Of the five monologues, three barely chip away at what makes masculinity toxic. Azeron’s Jun-jun has been lauded for his energy and willingness to go semi-nude. But he rushes through his set, leaving his story unintelligible, his hands like scarecrow fingers betraying him by revealing his perpetual tenseness. On the other hand, Adamos manages to pull out laughter as he, as Rob, shares how his wife found out about his bouts of infidelity. But he struggles with pace, his deep voice and calm demeanor at times threatening to lull the audience to sleep. Most painful is Jake Cuenca’s Peter — who begins as a fascinating embodiment of male rage and ego that quickly crumbles once his motivations and actions get convoluted, self-reflexive, and self-pitying.

Only a series of questions are left after each of these sets: Considering Azeron’s age and stature, why not focus on how looking perpetually young complicates dating? Considering that Adamos’ monologue already revolves around age, why not lean into how this complicates his desire for sexual experimentation? Why not use his own stories of dealing with incontinence to fuel a discussion on how the body betrays oneself when one gets older? Considering the seeming parallels between road rage and the taboo nature of sex work, why not have Cuenca’s monologue in a jail rather than a gym? Surely this serves as a better avenue for Cuenca, especially considering the confessional tone of his delivery?

DickTalk succeeds when it is less presentational and less instructive, when it commits to the slice-of-life and dinner-room-conversation quality of its material. Its stars have shown themselves capable enough in other fora — Azeron in Metamorphosis, Adamos in the recently concluded Maria Clara at Ibarra, Cuenca in Iron Heart and the upcoming Cattleya Killer. But all three of the monologues do not seem tailor-made for the people performing them, failing to capitalize on their talents and unable to subvert their public personas. This lack of specificity in the writing and the performance stems from confusing carefulness with thoughtfulness, and in the refusal to be provocative when provocation is the foundation of The Vagina Monologues’ success. The monologues in DickTalk are rendered generic, hollow, and discomforting in unenlightening ways.

The opposite can be said about Nodalo and Morales’ monologues, which seem to be built on stronger ground and clearer dilemmas. While a newcomer to theater, Nodalo is vibrant and celebratory, narrating the many ways he, as Rob, was accepted by family and friends throughout the process of transitioning, and it’s a welcome balm to the nihilism we are often subjected to when hearing stories from the LGBTQ+ community. But his speeches are regularly interrupted by a voice from the intercom deadnaming him — the sound of static shocking him into silence until he is able to compose himself to continue.

To most audience members, it may be a negligible detail, but it is jarringly effective at conveying the small ways oppression is still pervasive within institutions of care, especially towards trans individuals. One wonders why there aren’t more of these minute directorial decisions by Noble, the kind that contrasts the staging with the text to create something implosive in retrospect.

Of the five, Mikoy Morales stands out as Cecile — a straight man often dumped by his girlfriends, convinced he is gay due to his effeminate behavior and interests. From having crushes on Miss Universe contestants to arguing with his fiancee about the difference between dusk pink and red, the complexities of Cecile’s life unfolds to the audience as a series of breakup sagas, each increasingly incredulous rant teetering between misunderstanding and male entitlement.

It helps that Morales is at ease with the text — speeding up and slowing down to emphasize details, constantly interacting with the audience, even winking at several girls until they woo. It’s a masterclass in crowdwork, a skill that doesn’t seem necessary until one gets a taste of it. While the believability of Cecile’s bookends are spoiled by triteness and melodrama, requiring Morales to feign tears when simpler gestures are more effective, one cannot help but feel emotional for Cecile as he is hit by the reality of his confessions, when he realizes that the prospect of love may never come.

The novelty of the monologue comes from the specificity of the voice behind it. Whatever caricature is painted in its first few minutes falls away as the audience begins to share Cecile’s ache and yearning, as it begins to touch on more universal themes of predetermination. It places us squarely in his subjectivity, teaches us to be his friend, and then reveals how we have, in our own lives, caged him or someone like him through our prejudices and judgements. By describing himself, Cecile also describes the kinds of women who won’t tolerate femininity in men, who also unconsciously uphold the same patriarchal ideals handed down to them by their ancestors, who remain stuck in the binaries that keep even their loved ones unhappy.

It is the presence of this truly excellent monologue that makes DickTalk all the more disappointing. It is work whose ambitions get the best of it, whose desire for spectacle gets in the way of the intimacy and proximity needed to make it work. It’s difficult to watch promising premises get fumbled in execution. Maybe it just needs more time, more thought, more money, more perspectives, more rewrites, more maturity. But maybe DickTalk is just flaccid work that no pill can instantly cure. – Rappler.com

DickTalk ran from April 15-16, 18-20, and 21 and 23 at the Carlos P. Romulo Auditorium of RCBC Plaza and is projected to have a re-run in June or July 2023.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.